Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura, Linnaeus 1758)

Physical appearance. The Turkey vulture, is also named the turkey buzzard or buzzard in some parts of the United States, and the John Crow or Carrion Crow in the Caribbean. It is one of the three species of the Genus Cathartes Illiger, 1811. The others are the Yellow-headed and Greater Yellow-headed vultures which are also sometimes named as Turkey vultures. The Turkey vulture is sometimes called the Red-headed Turkey vulture to distinguish it from these other Cathartes vultures.

The Turkey vulture is considered a large bird in the Americas, but it is small compared with the large Old World vultures and slightly smaller than the Hooded and Egyptian vultures. The head, body and tail measures 62-81 cm (24-32 in) and the wingspan is about 160-183 cm (63-72 in). The bird weighs about 0.8 to 2.3 kg (1.8 to 5.1 lbs). This species is another example of Bergmann's Rule, with size increasing northwards. Central and South American birds are usually smaller, about 1.45 kg (3.2 lbs), while those from northern North America may weigh about 2 kg (4.4 lbs) (Hilty 1977; Kirk and Mossman 1998; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Meiri and Dayan 2003).

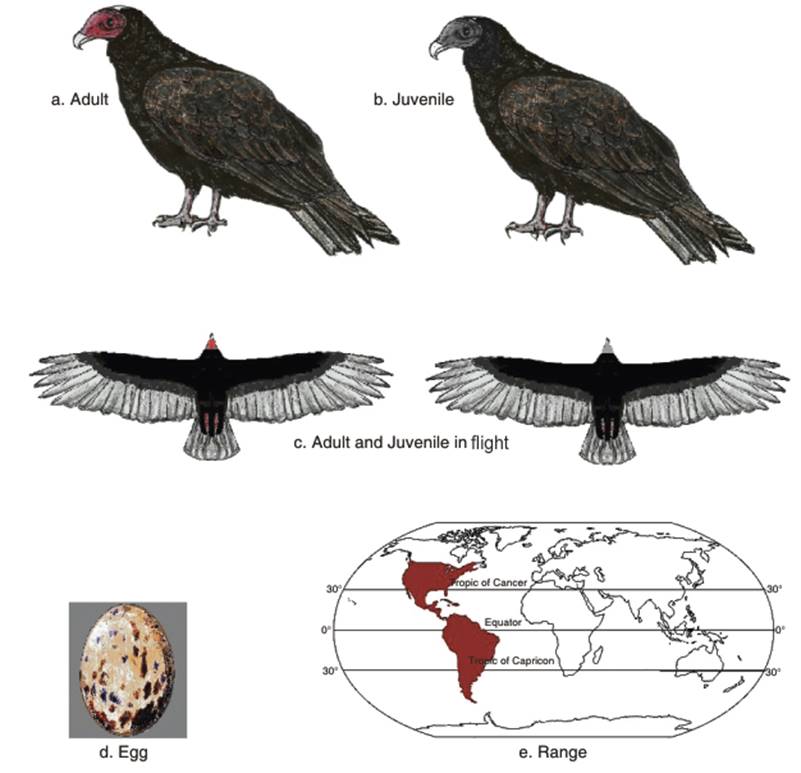

In coloration, the body feathers are brownish-black (Fig. 3.2 a,b,c). The flight feathers on the underwings are silvery-gray, which contrasts with the blackish-brown to black wing linings. The head of the adult is red and featherless, although some individuals may have a small amount of blackish down on the top of the neck. The bill is white and the feet are pink, but may be stained white due to the Cathartid habit of defecating on the legs for cooling purposes (Terres 1980; Feguson-Lees and Christie 2001). As the nostrils are perforate, not divided by a septum, it is possible to see through the bill (Allaby 1994). Although it is of similar size to the Black Vulture, it has a longer tail and wings, and flies with less flapping. In flight, it may be distinguished from the Bald and Golden Eagles, and large Buteo buzzards by the much smaller head, and the wings held in a broad 'V' shape. Also, its wings wobble from side to side when in soaring flight, unlike the flat wing positions of the eagles and buzzards. Similar to the Black vulture there are leucistic (sometimes mistakenly called 'albino') Turkey vultures (Kirk and Mossman 1998).

Fig. 3.2. Turkey Vulture

Classification. The number of subspecies of Turkey vulture is disputed. Some publications report five, others six subspecies. Where five subspecies are listed, they are; C. a. aura (L. 1758), C. a. jota (Molina, 1782), C. a. meridionalis (Swann, 1921) or C. a. teter (Friedmann, 1933), C. a. septentrionalis (zu Wied, 1839) and C. a. ruficollis (von Spix, 1824). C. a. aura the nominate and smallest subspecies, occurs from Florida and Mexico south to Costa Rica, and the Greater Antilles into South America and in coloration is very similar to C. a. meridionalis (Amadon 1977).

C. a. meridionalis and C. a. teter, named the Western Turkey vulture are synonymous. The name meridionalis was created by Whetmore (1964) for the western birds of C. a. teter, which was classified as a subspecies by Friedman in 1933. This subspecies breeds from southern Canada to the southwest of the United States and northern Mexico (Peters et al. 1979). It also migrates to South America, wintering from California to Ecuador and Paraguay and there occurring with the smaller C. a. aura.

C. a. ruficollis is found on the island of Trinidad, southern Costa Rica and Panama, and south to southern Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina (Brown and Amadon 1968). It is a darker bird than C. a. aura, and the brown wing edgings are usually absent or narrower (Brown and Amadon 1968). In addition, the dull red head may have yellowish- or greenish-white markings, and a yellow crown patch in adults (Blake 1953).

C. a. jota also called the Chilean Turkey vulture, is a larger, browner bird than C.a. ruficollis and may also be distinguished from C. a. ruficollis in being slightly paler, within grey margins to the secondary feathers and wing coverts (Blake 1853; Hellmayr and Conover 1949). It occurs from southern Colombia to southern Chile and Patagonia.

C. a. septentrionalis, the Eastern Turkey vulture, which occurs in southeastern Canada south through the eastern United States, may be distinguished from C. a. teter, as in the latter the edges of the lesser wing coverts are darker and narrower (Amadon 1977). These two subspecies also differ in wing and tail proportions and the eastern bird rarely migrates south of the United States (Amadon 1977). This species winters in the southern and eastern United States.

C. a. falklandicus (or C. a. falklandica, named by Sharpe 1873, Bang 1972 and Breen and Bildstein 2008) is a sixth subspecies not always mentioned. It occurs on the coast of western South America from Ecuador in the north to Tierra Del Fuego and the Falklands (Malvinas) in the south. However, Dywer and Cockwell (2011) and Van Buren (2012) record the Turkey vultures on the Falklands as C. a. jota. Hellmayr and Conover (1949) considered the separation of the birds of the Falklands Islands from C. a. jota as 'impracticable.'

Other subspecies have been mooted. These included C. a. insularis and C. a. magellanicus. These were not recognized by many authors including Stresemann and Amadon (1979). C. a. teter was seen as a synonym of C. a. meridionalis and C. a. insularum was classified as a synonym of C.a. aura. Some authors, including Houston (1994) have merged C. a. meridionalis and falklandica into C. a. aura and C. a. jota, respectively. Also, molecular studies may result in two subspecies, C. a. ruficollis and C. a. jota, being upgraded into species (see for example Jaramillo 2003).

Foraging. Unlike the Black vulture which is described as nonmigratory, 'or nearly so' throughout its range, the Turkey vulture is migratory in most of its range (Jackson 1983: 245). It frequents many landcover types, including pastures, grasslands, and sub-tropical and tropical forests (Hilty 1977; Kaufman 1996). In Argentina, Carette et al. (2009) record it as more affected by habitat fragmentation than the Black vulture. In Guyana, recorded habitat includes savanna grasslands, scrub or brush habitat, white sand scrub, bush islands and habitats altered by humans, such as gardens, towns, roadsides, agricultural lands, disturbed forests and forest edge (Braun et al. 2007: 9). In the United States, it frequently forages and roosts in urban areas (United States Department of Agriculture USDA 2003).

Turkey vultures and other members of the Genus Cathartes have a strong sense of smell (Stager 1964; Houston 1986, 1988; Graves 1992). For this reason, they can detect food in close-canopied forests. The olfactory lobe (which processes smells) is larger than that of most birds (Snyder and Snyder 2007). Lowery and Dalquest (1951) report that Turkey vultures routinely located meat invisible from the air above, under logs or tree base hollows. Due to its sense of smell it leads the Black vulture and King vulture to carcasses (neither have a sense of smell) but may be displaced by them in competition on the ground (the social Black vulture may prevail due to its greater numbers, the King vulture may prevail due to its size). Wallace and Temple (1987) noted that in one-to-one encounters at carcasses, Turkey vultures prevailed over Black vultures in slightly more than half of the encounters, although the Turkey vultures could be overwhelmed by superior numbers of Black vultures. In some cases, the stronger King vulture assists the Turkey vulture by tearing open carcasses (Gomez et al. 1994; Muller-Schwarze 2006; Snyder and Snyder 2006).

It feeds on all types of carrion, including garbage, coconuts, oil-palm fruit and even salt (Pinto 1965; Coleman et al. 1985; ffrench 1991). In some cases, they have been known to attack live fish, young ibises and herons and tethered or netted birds (Mueller and Berger 1967; Brown and Amadon 1968). Campbell (2007: 275) writes that the Turkey vulture 'also feeds on a wide variety of small and large wild and domestic birds as well as dead fishes, amphibians, reptiles, stranded mussels, snails, grasshoppers, crickets, mayflies, and shrimp when they are available' (see also Brock 1896; Keyes and Williams 1888; Pearson 1919; Tyler 1937; Rivers 1941; Rapp 1943; James and Neale 1986; Buckley 1996). Campbell et al. (2005: 108) also listed several food sources in British Colombia, Canada; these included invertebrates (sea cucumbers, marine worms, sea stars, sea urchins, octopus), fishes (several salmon species and dogfish), toads, reptiles (garter snakes, rattlesnakes), birds (mostly waterbirds and domestic fowl), and mammals (wild and domestic species, ranging in size from moles to black bears).

In the United States, they have also been recorded eating fish (Cringan 2007). Other records are iguana in Mexico (Lowery and Dalquest 1951); snakes, rats and other animals killed in burnt cane fields in Mexico (Young 1929); road kills, feces and fruits, including macahba palm (Acrocomia sclerocarpa (Jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart.) and oil palm or dende (Elaeis guineensis, Jacq.) in Brazil; large birds, such as storks, mid-sized mammals such as armadillos, crab-eating foxes, coatis, crab-eating raccoons, nutrias, and tayras, and reptiles such as turtles and snakes in Argentina (Di Giacomo 2005); and pickings from sea lion colonies and sheep ranches in the Falklands (Woods and Woods 2006). In the case of sheep, it has been blamed for killing sheep during the lambing period, and eating the tongues and eyes of sheep (Brooks 1917) or attacking weak sheep (Woods 1988). The bird defends itself by regurgitating semi-digested meat, which may repel an attacker or nest raider (Fergus 2003).

Turkey vultures roost communally year-round. In one study, the possibility of roosting sites being used for the spread of foraging information was examined (Rabenold 1983). Communal roosts are also recorded as offering energy savings through thermoregulation, opportunities for social interactions, and a reduced risk of predation (Buckley 1998; Kirk and Mossman 1998; Devault et al. 2004). The Turkey vulture is gregarious and roosts in large community groups, breaking away to forage independently during the day. Several hundred vultures may roost communally in groups which sometimes even include Black Vultures. It roosts on dead, leafless trees, and will also roost on man-made structures such as water or microwave towers.

Breeding. Turkey vultures, similar to Black vultures, normally do not build a nest; the eggs are laid in a crevice in rocks or on a cave floor, a hollow stump or even in sugarcane fields (Cuba), or old hawk nests (Brazil) (Brown and Amadon 1968). In Saskatchewan, nests were recorded in caves or on the ground in dense cover, brush piles or vacant buildings (Houston 2006; Houston et al. 2007). Nests in the United States have been recorded under rocks or logs, in caves, or on the ground, rarely in tree cavities (Maslowski 1934). Sick (1993) recorded nests in dead buriti palms in northwestern Bahia, Brazil. In the Falkland Islands, nesting usually takes place in deserted buildings, in caves or on the ground under tussac grass (Woods and Woods 1997).

The egg-laying period starts at different times in different periods, but the incubation period is 30-41 days. In Trinidad the recorded period is from November to March (Belcher and Smooker 1934). In British Columbia and Saskatchewan, Canada, egg-laying was recorded from mid-May to early June, and the eggs hatched from late June to early July, with fledgling in September (Campbell et al. 2005; Houston 2006). In the Falkland Islands, the egg-laying mostly occurred between mid-September and late October (Woods 1988; Woods and Woods 1997), with fledgling in January (Woods and Woods 2006). The clutch size is usually two creamy-white, reddish or brown spotted eggs (Fergus 2003) (Fig. 3.2d).

Population status. The Turkey vulture has the widest range of the New World vultures from southern Canada to southern South America. The total population is estimated at about 4,500,000 individuals (BirdLife International 2012). Seamans (2004) and Sauer et al. (2001) write that Turkey vulture populations have increased at an annual rate of 3.4% in eastern North America, 19662000. Roost and nest sites isolated from humans have become limited due to increased urbanization (Rabenold and Decker 1989). The United States Department of Agriculture USDA (2003: 1) states that 'Turkey vultures have become increasingly abundant throughout the northeast' parts of the United States. Along with the Black vulture, the Turkey vulture has been linked to 'property damage and nuisance problems' and 'both species jeopardize aircraft safety when in or around airport environments and are involved in wildlife-aircraft collisions (birdstrikes).' Also, similar to the Black vulture in the United States, Turkey vultures roost in urban areas such as 'backyard trees, in town, or even on suburban rooftops' (see also Tyler 1961; Rabenold 1983; Mossman 1989; Davis 1998; Lowney 1999; Lovell and Dolbeer 1999).

The USDA defines nuisance behavior as 'unwanted congregations of these birds around areas of human activity (homes, schools, churches, shopping areas) resulting in accumulations of feces on trees and lawns, residential and commercial buildings, electrical and radio transmission towers, and other structures.' The results of their presence can include 'unpleasant odors emanating from roost sites' and in some cases 'accumulations on electrical transmission towers have resulted in arcing and localized power outages... and public water supplies have been contaminated with fecal coliform bacteria as a result of droppings entering water towers, springs, or other sources.' Other property damage attributed to vultures includes the tearing and possible consumption of asphalt shingles and rubber roofing material, rubber, vinyl, or leather upholstery from cars, boats, tractors, and other vehicles, latex window caulking, and cemetery plastic flowers.

Yellow-headed Vulture (Cathartes burrovianus Cassin 1845)

Physical appearance. The Yellow-headed vulture, also known as the Lesser Yellow-headed vulture, Lesser Yellow-headed Turkey vulture or Savanna vulture, is the smallest member of the Genus Cathartes, generally smaller than the Turkey vulture or the Greater Yellow-headed vulture. The head to tail length is about 53-66 cm (21-26 in), with a wingspan of about 150-165 cm (59-65 in). The weight range is about 0.95 to 1.55 kg (2.1 to 3.4 lb) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

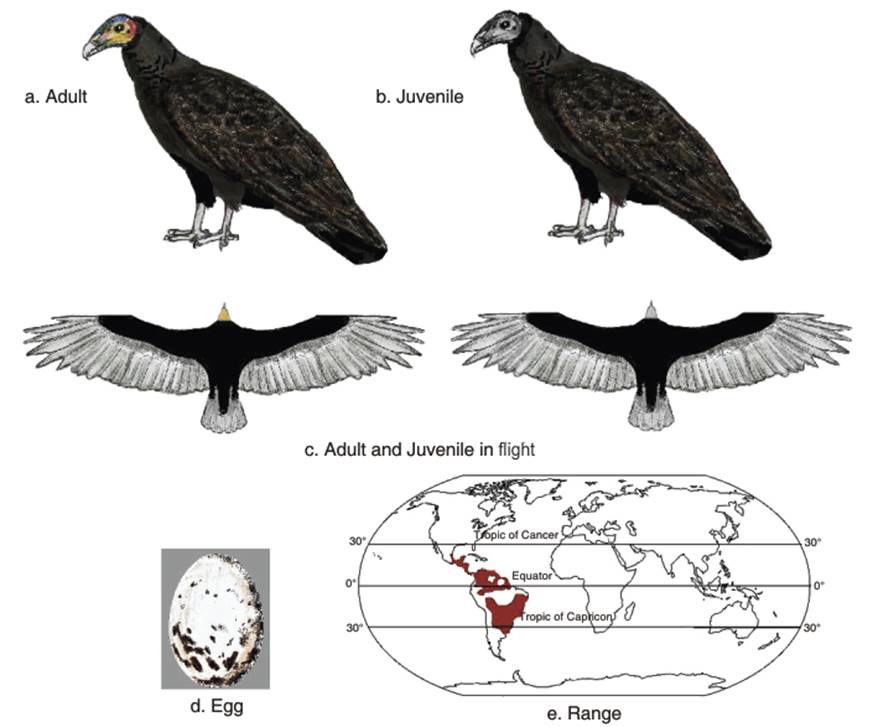

The plumage is black, with a greenish or bluish gloss, and the under parts are usually duller and more brownish (Fig. 3.3 a,b,c). Blake (1977) describes the head as yellowish to orange, 'varied by prominent blue markings bordered with green on crown'. The forehead and nape are usually reddish and the crown is greyish blue to bluish grey. The bill is buff colored to dull ivory white and the legs are dull white or off-white. The rounded tail is short, shorter than that of the Turkey vulture, but like the latter it has a perforated nose.

The juvenile has browner plumage a whitish rather than reddish nape and darker colored skin on the head, and more yellowish legs (Blake 1977; Hilty 1977). This species may be distinguished from the Greater Yellow-headed vulture by its smaller size and lighter build; shorter, thinner tail; browner, less glossy black plumage; lighter colored legs; more orange, less yellow skin on the head; less steady flight; and primarily savanna rather than forest habitat (Amadon 1977; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

Fig. 3.3. Yellow-headed Vulture

Classification. The Lesser Yellow-headed vulture was first recorded by John Cassin (Cassin 1845). Two subspecies are generally recognized, similar except in size (Blake 1977). The nominate subspecies Cathartes burrovianus burrovianus Cassin, 1845, is the smaller of the two, and occurs from Mexico southwards through Central America to northwestern South America (Amadon 1977). The second subspecies, Cathartes burrovianus urubitinga recorded by August von Pelzeln in 1861, is larger and ranges from Colombia southwards to Argentina (Blake 1977). Despite the existence of two subspecies, Dickinson (2003) described the species as monotypic.

This species was in the past regarded as a superspecies with the Greater Yellow-headed Vulture (Amadon and Bull 1988) despite the fact they are sympatric in many contexts, and despite the habitat differences of savanna and forest (the latter bird is sometimes called the Forest vulture) (Houston 1994). In the past, it was wrongly named C. urubitinga (Pinto 1938; Hellmayr and Conover 1949; Wetmore 1950), but later the name burrovianus was prioritized (Stresemann and Amadon 1979).

Foraging. The Yellow-headed vulture flies singly and in flocks, and has been described as flying at lower altitudes than the Turkey vulture (Belton 1984). Like the Turkey vulture, this species has a strong sense of smell (Stager 1964; Houston 1986, 1988; Graves 1992). Reports from different countries illustrate adaptive behavior in foraging, which are enabled by its olfactory powers.

It generally occurs in open terrain (hence its other name, Savanna vulture) including freshwater or brackish and marshes, moist savannas, mangrove swamps, scrubland and scrub savanna, open and moderately wooded margins of rivers, and farmland and ranches in some areas (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). In a case study in Brazil, it occurred only in savanna with lagoons (Zilio et al. 2013). In Guyana, Braun et al. (2007) gave its habitat as savanna grasslands, scrub or brush habitats, including white sand scrub, bush islands; also fresh water habitats, including lakes, impoundments, ponds, oxbows, marshes, and canals. In Nicaragua, habitat types included forest edge and secondary pine dominated savanna (Marfinez-Sanchez and Will 2010). In Brazil, habitats included uncultivated, mixed riverine and marsh vegetation (Sick 1993). In Mexico, some individuals were even recorded behind harvesting equipment (Pyle and Howell 1993).

Fishes and reptiles are mentioned as common favorite foods (Wetmore 1965; Pyle and Howell 1993; Sick 1993). For example, some individuals killed and ate pool-stranded fish in Costa Rica (Stiles and Skutch 1989) and Panama to the neglect of mammal carcasses (Wetmore 1965). However, Di Giacomo (2005) records this species feeding on road-killed cats and dogs, and also dead wild animals such as anteaters (Tamandua tetradactyla), crab-eating foxes (Cerdocyon thous), nutrias (Lontra longicaudus), coatis (Nasua nasua), and capybaras (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris). It was also observed eating carcasses of reptiles such as boas (Eunectes notatus), other snakes (e.g., Hydrodynastes gigas) and lizards; also toads (Rhandia cv. quelen) (Tupinambis merianae), and fish (Hoplias cf. malabaricus) and eels (Synbranchus marmoratus).

Breeding. No nest is built, similar to other members of the Genus Cathartes. The eggs are laid in a tree hollow (Sick 1993) or on the ground in dense grass (Yanosky 1987). For example, Di Giacomo (2005) describes 13 nests in Argentina, all on the ground, in dense grass patches called 'chajape' (Imperata brasiliensis), in 'paja colorada' (Andropogon lateralis), dense stands of large bromeliads (Aechmea distichantha) and grass 'pajonal de carrizo' (Panicum pernambucense) (Di Giacomo 2005).

The average clutch size is of two creamy-white (with grey to reddish splotches) eggs (Wolfe 1938; Di Giacomo 2005) (Fig. 3.3d). The incubation period at an Argentine nest was 40 days, and the nestling period was between 70 and 75 days (Di Giacomo 2005).

Population status. The distribution of the Yellow-headed vulture is shown in Fig. 3.3e. The range is very large, and the population is recorded as stable. It is described as common to fairly common throughout most of its range. It is fairly common in Mexico and Central America (Howell and Webb (1995). This was also the more recent assessment for southern and eastern Mexico (southern Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Tabasco, Chiapas, Yucatan Peninsula, and on both slopes of Oaxaca) southward into Central America (AOU 1998).

It has variable status in Central America. In Belize it was fairly common in open country and mangroves (Russell 1964; Jones 2003). In Guatemala it has been extensively recorded in lowlands, coastal areas and lagoon fringes (Dickerman 1975; Thurber et al. 1987; Dickerman 2007; Eisermann and Avendano 2007). In El Salvador it is described as a visitor or a resident (Thurber et al. 1987; Komar and Dominguez 2001; Jones 2004). In Honduras, it is common in the pine savanna of Mosquitia and marshy habitat throughout, outnumbering the Turkey vulture. Opinions differ on its breeding status (Monroe 1968; Jones 2003; Anderson et al. 2004). It is regarded as rare in Nicaragua, but possibly more common in the Caribbean Region (Martinez-Sanchez and Will 2010). Sightings have been confirmed across the country, especially on the Caribbean coast, but also on the Pacific side (Howell 1972; Jones and Komar 2007, 2008; McCrary et al. 2009). In Costa Rica it is a variably common resident, especially in the Guanacaste Province and Rio Frio region (Slud 1964; Orians and Paulson 1969; Stiles and Skutch 1989; Jones and Komar 2010). In Panama, it is fairly common in the savannas, grasslands and open marshes, especially the Pacific coast, but some argue it might be migratory as most sightings are during the rainy season (Wetmore 1965; Ridgely and Gwynne 1989).

This species also has a variable status in South America. In Colombia, it is common in open marshy landcovers and moist grasslands (Hilty and Brown 1986; Marquez et al. 2005). In Ecuador, there are disputed and unconfirmed sightings, at least one believed to be C. melambrotus (Salvadori and Festa 1900; Albuja and de Vries 1977; Pearson et al. 1977; Tallman and Tallman 1977; Ridgely and Greenfield 2001). It is rare in Peru, but occurs along grassy, riverine marshes east of the Andes (Clements and Shany 2001). It is fairly common in Venezuela (Hilty 2003) and Guyana (Braun et al. 2000). In Brazil, it occurs mostly in the Northeast and the Amazon region (Sick 1993) and parts of the Rio Grande do Sul in the south (Belton 1984). In Paraguay it is common throughout, but rare in the humid forested Alto Parana (Hayes 1995; del Castillo and Clay 2004). It is common in Argentina, especially at Reserva El Bagual, Formosa Province (Di Giacomo 2005). It is resident but not common in Uruguay, usually in lowlands near Laguna Merin and uncommon in the rest of the country (Arballo and Cravino 1999). On the Caribbean coast of South America, it is commonest in Guyana (Braun et al. 2007), and less common in French Guiana (Thiollay and Bednarz 2007) and Suriname (Haverschmidt and Mees 1994). In Trinidad, its occurence is disputed (Belcher and Smooker 1934; Junge and Mees 1958; Herklots 1961; ffrench 1991). One possible sighting was recorded, but this could actually have been a Turkey vulture, as the local Turkey vulture usually has a yellow nape (Murphy 2004).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 226;