Greater Yellow-headed Vulture (Cathartes melambrotus, Wetmore 1964)

Physical appearance. The Greater Yellow-headed Turkey vulture is also known as the Forest vulture, thus distinguishing its preferred habitat from that of its close relative the Yellow-headed or Savanna vulture. It is larger than the Yellow-headed vulture; the length is 64-75 cm (25-30 in), and the wingspan about 166-178 cm (65-70 in). The weight is about 1.65 kg (3.6 lb). The body plumage is blacker, with a glossier, greenish or purplish sheen than that of the Yellowheaded vulture (Fig. 3.4 a,b,c).

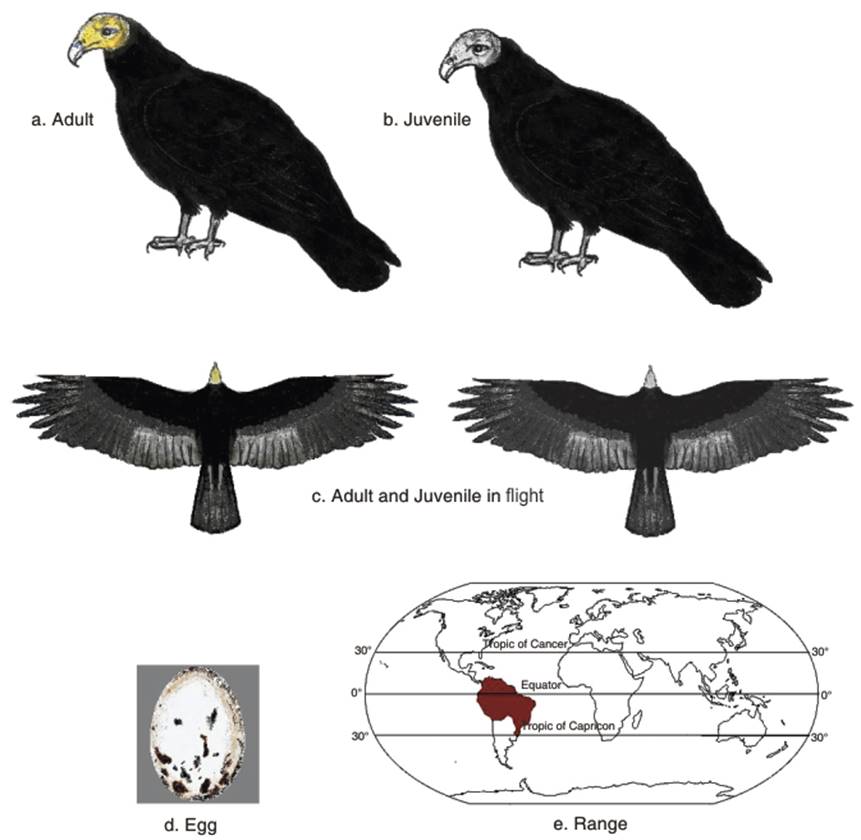

Fig. 3.4. Greater Yellow-headed Vulture

The bare skin of the head is orangish-yellow to yellowish-orange. The nape and the skin close to the nostrils are pink. In flight, the upper wing surface and back are glossy black, while on the underside the flight feathers are slightly lighter grey. The rest of the wing feathers are black. Towards the primary wing feathers, there is a darker band of feathers from the front edge to the back of the wing, similar in color to the tail. This contrasts with the lighter colored flight feathers, and is almost as black as the feathers of the underside of the body. Similar to the Turkey vulture, the tail is long and rounded. The legs are blackish, but may be lighter due to the habit of defecating on the legs. The plumage of the juvenile is similar to adult, but has greyish skin on the head (Brown and Amadon 1968; Hilty 1977).

This species is commonly contrasted with the Yellow-headed vulture, therefore identification must be based on a comparison. It may be distinguished by its larger size and bulkier build; broader, longer tail and broader wings; darker, glossier plumage; darker colored legs; yellower skin on the head, with less orange and pink; steadier flight movement; and darker inner primaries, contrasting with the lighter colored outer primaries and secondaries (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). It also prefers forest, unlike the savanna preference of the Yellow-headed vulture (Amadon 1977). Compared with the similarly sized Turkey vulture, the Greater Yellowheaded vulture is distinguished by the yellow rather than red head, and the band of darker feathers vertically crossing the wings, and the slightly darker primaries and secondaries (Ridgely and Greenfield 2001).

Classification. The Greater Yellow-headed vulture was considered as the same species as the Yellow-headed vulture, until 1964 (Wetmore 1964). Although Amadon and Bull (1988) described the two species as merely one super species, they are largely sympatric, but occur in different habitats, forest and savanna.

Foraging. This species forages in the moist, dense, lowland forest, while generally avoiding high-altitudes and non-forested areas (Hilty 1977; BirdLife International 2014). For example, in a study in Guyana, Braun et al. (2007: 10) describe its habitat as lowland forest, including both seasonally flooded and non-seasonally flooded forest. It generally roosts on tall trees, allowing landscape surveys. A generally solitary bird, it only rarely flies in groups (Hilty 1977). Schulenberg (2010) notes that the Greater Yellow-headed vulture is 'ecologically separated from the other members of the genus, occurring exclusively over large tracts of undisturbed lowland forest in Amazonia and the Guyanas.'

As it commonly forages over dense forests, possibly more than any other New World vulture, it necessarily uses smell to locate carcases, usually those primates, sloths and opossums (Stager 1964; Houston 1986, 1988; Graves 1992). Graves (1992: 38) wrote that 'although the olfactory capacities of the Greater Yellow-headed vulture (C. melambrotus) are unknown, they are thought to be similar to those of its congeners', namely the other members of Cathartes (see also Houston 1988). It has also been recorded as preferring fresh meat, which may be more difficult to detect at the earlier stages of putrefaction (Snyder and Synder 2006; Von Dooren 2011; Wilson and Wolkovich 2011).

Graves (1992) gives evidence of the olfactory senses of the Greater Yellow-headed vulture in a case study of dense forest on the east bank of the Rio Xingu, 52 km SSW of Altamira, Patti, Brazil. The occurrence of the different vulture species was segregated by the vegetation; in the pristine forest, the Greater Yellow-headed vulture was by far the most numerous. The Black vultures, with their poor sense of smell, only foraged for fish over sandbars and never over unbroken forest. King vultures were observed soaring high over the river.

However, due to its comparatively weak bill, it is often dependent on larger vultures, such as the King vulture, to open the hides of larger animal carcasses. The King vulture's olfactory senses are too weak to track carrion in the forest; hence, it follows the Greater Yellow-headed vultures to carcasses, where the King vulture tears open the skin of the dead animal, allowing the smaller vultures to feed. In some instances, the Greater Yellow-headed vulture is driven from food by the larger vulture (Gomez et al. 1994). In relations with the Turkey vulture, some authors conclude that the Greater Yellow-headed vulture is dominant (Schulenberg 2010), while others state the reverse (Hilty 1977).

Breeding. Schulenberg (2010) states that 'perhaps due to its preference for un-disturbed lowland rainforest and the general inaccessibility of this habitat, no nest site has ever been found for this species.' However, numerous accounts describe the nesting features and habits. This species, similar to others in the Genus Cathartes does not build a nest, but lays its eggs on cave floors, in crevices or in tree hollows. The eggs are cream-colored with brown blotches (Fig. 3.4d). It lays one to three eggs, but the common number is two. Fledging takes place about two to three months later (Hilty 1977; Terres 1980; Howell and Webb 1995).

Population status. The distribution of the Greater Yellow-headed vulture is shown in Fig. 3.4e. Like the other members of the Genus Cathartes, the Greater Yellow-headed vulture has a large range, and is therefore not considered a threatened species, though it may be declining in numbers (del Hoyo et al. 1994; Ogada et al. 2011; BirdLife International 2014). It is found in the Amazon Basin of tropical South America; specifically in south-eastern Colombia, southern and eastern Venezuela, Guyana, French Guiana, Suriname, northern and western Brazil, northern Bolivia, eastern Peru and eastern Ecuador. It has not been recorded in the Andes, in the lowlands to the west or north of these mountains, in more open landcover in northern South America, eastern South America, or in the subtropical regions to the south of the continent (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 241;