Andean Condor, Vulturgryphus (Linnaeus 1758)

Physical appearance. The Andean condor is the only member of the Genus Vultur (Linnaeus 1758), as other species such as the King vulture and the California condor have been removed from this genus. The Andean condor is about seven to eight cm shorter in length than California condor, about 100 to 130 cm (3 ft 3 in to 4 ft 3 in) (Del Hoyo et al. 1996; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2000). However, it usually has a larger wingspan of 270 to 320 cm (8 ft 10 in to 10 ft 6 in) and generally weighs more, about 11 to 15 kg (24 to 33 lb) for males and 8 to 11 kg (18 to 24 lb) for females.

The Andean condor is sometimes cited as the world's largest flying bird; however it has some rivals. In terms of the heaviest average weight for a flying bird measured by weight and wingspan, it is exceeded by the Dalmatian Pelican (male bustards may weigh more, but are not considered full flying birds, rather ground dwellers) (Del Hoyo et al. 1996; BirdLife International 2014). In terms of the wingspan, although the largest albatrosses and pelicans have longer wings (the Wandering Albatross 3.6 m/12 ft, the Southern Royal Albatross, the Dalmatian and the Great White Pelican 3.5 m/11.6 ft), the Andean condor lays claim to the largest wing surface area of any living bird (Wood 1983; Harrison 1991; Ferguson- Lees and Christie 2001).

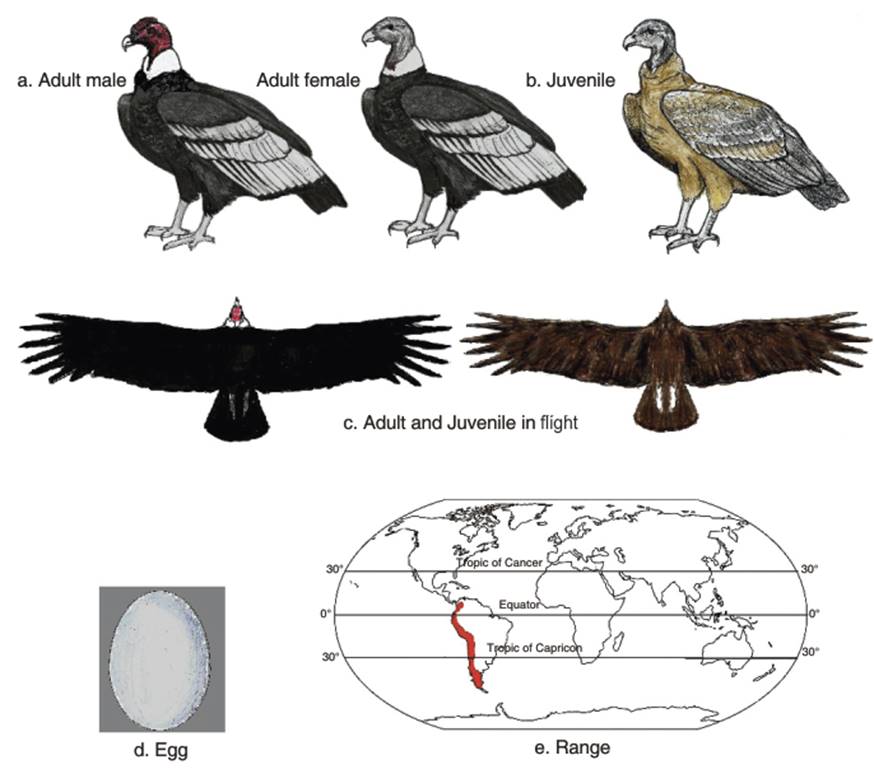

The bare skin of head and neck are dull red, which may change to a stronger red color when the bird is excited, for example during the mating season (Whitson and Whitson 1968). The male has a dark red comb or carbuncle on the top of the flattened head (Fig. 3.7 a,b,c). There is a visible ruff of white feathers at the base of the neck. In the adult, the plumage is black with large white patches on the wings, which do not appear until the completion of the bird's first moulting (Hilty 1977). Juveniles have blackish skin on the head and neck, brown collar ruffs and grey-brown plumage (Blake 1953).

Fig. 3.7. Andean Condor

Classification. The Andean condor is the only accepted living species of its genus, Vultur. As noted by (Griffiths 1994), it was formerly included in the Genus Sarcoramphus, with the Kibg vulture, but using syringeal morphology it was returned to Vultur (Griffiths 1994). There is little prehistoric fossil evidence for the Andean condor, compared with the California condor, which is well documented in fossil remains. Some fossil remains from the Pliocene-Pleistocene were revealed to be the modern species, rather than an ancestral species, and remains found in a Pliocene deposit of Tarija Department, Bolivia, possibly could be a smaller subspecies, named V gryphus patruus (Fisher 1944).

Foraging. The condor, primarily a scavenger of large carcasses, prefers high, open terrain, such as grasslands, alpine meadows, rocky mountains up to 5,000 m (16,000 ft); occasionally it descends to lowlands in eastern Bolivia and southwestern Braziland and lowland desert areas in Chile and Peru, and is found over southern-beech forests in Patagonia (Sibley and Monroe 1990; Houston 1994; Parker et al. 1996; BirdLife International 2014). Similar to the California condor, and the Old World giants the Cinereous and Himalayan Griffon vultures it forages over very large areas, traveling more than 200 km (120 mi) a day in search of suitable food (Lutz 2002). Due to its weight and large size, it generally roosts in elevated areas such as rock cliffs which allow take-off without much wing-flapping effort, and where thermals are easily available (Benson and Hellander 2007).

Food sources include carcasses of large, wild animals such as llamas (Lama glama, Linnaeus 1758), alpacas (Vicugna pacos, Linnaeus 1758), guanacos (Lama guanicoe, Muller 1776), rheas (Rhea americana, Linnaeus 1758) and armadillos (Dasypodidae spp., Gray 1821). More recently, food has included the carcasses of domestic livestock (cattle, horses, donkeys, mules, sheep, pigs, goats and dogs) and introduced species such as boars (Sus scrofa, Linnaeus 1758) and red deer (Cervus elaphus, Linnaeus 1758) (Newton 1990; del Hoyo et al. 1994; Swaringen et al. 1995). Commoner remains are those of domestic animals, such as cattle, horses, sheep, goats and dogs. In coastal areas, beached carcasses of marine cetaceans are also eaten. Andean condors may also hunt small, live animals, such as rodents and birds and rabbits. In feeding, male condors dominate females and displace them to lower quality areas (Donazar et al. 1999; Carrete et al. 2010).

It is usually dominant over other avian scavengers, such as Turkey, Yellow-headed and Black vultures (Wallace and Temple 1987), although some studies have shown otherwise (Carrete et al. 2010). Recently, the increased range of the Black vulture has increased the presence of the smaller bird at carcasses. Although dominance hierarchies are usually related to size (Wallace and Temple 1987; see also the chapters in this book on Old World vultures, where the larger vultures such as the Cinereous, Lappetfaced and large griffons, are dominant over smaller vultures), between the Andean Condor and the Black vulture 'carcass consumption seemed to be determined by species abundance' rather than only size (Carrete et al. 2010: 385; see also Mikami and Kawata 2004). Although during this study, Andean condors arrived first to 76% of carcasses in mountains, and Black vultures arrived first to 72% of carcasses in plains, the numbers of male and female Andean condors feeding at carcasses were negatively related to the abundance of Black vultures (both in plains and mountains, but more so in the plains). Therefore, Black vultures may 'represent a serious obstacle' to Andean Condor feeding (Carrete et al. 2010: 385).

Breeding. The Andean condor is recorded as principally a cliff or rock ledge nester. Some nests have been recorded at elevations of up to 5,000 m (16,000 ft) (Fjeldsa and Krabbe 1990). In places with few cliffs, such as coastal Peru, a nest may be created in cavities scraped among boulders (Haemig 2007). The nest, composed of a few sticks on the bare ground, contains one or two bluish-white eggs (Fig. 3.7d). The egg-laying period is from February to March every second year, and incubation lasts about 54 to 58 days. The period before fledging is about six months (Cisneros-Heredia 2006).

The Andean condor has been described as communal rooster at least on some occasions. Donazard and Feijoo (2002) noted that within large groups of birds there are hierarchies. Birds segregated by sex and age in summer and autumn communal roosts in the Patagonian Andes. It was observed that condors preferred roosting places that received earlier sun at sunrise (summer) and also later sun at sunset (autumn). There was also selection of sheltered crevices. It is hypothesized that sunny areas enabled occupying birds to increase foraging, plumage care and maintenance times, and also to avoid the colder temperatures.

In competition for favored places, adults dominated juveniles and males dominated females within each age class. In consequence, 'fighting and subsequent relocating led to a defined social structure at the roost', with mature males clustering as the most dominant, and immature males as the least dominant; it is inferable that 'irregularity in the spatial distribution and aggregation patterns of Andean Condors may be the result of requirements for roosting' (Donazard and Feijoo 2002: 832).

Population status. The distribution of the Andean condor is shown in Fig. 3.7e. The breeding range in the 19th century stretched from western Venezuela to Tierra del Fuego, i.e., along the whole of the Andes mountain range. Currently, the impacts of human activity have contributed to a contraction of this range (Haemig 2007). Negative effects may also stem from reductions in predatory mammals and livestock (Lambertucci et al. 2009) and interspecific competition with Black vultures (Carrete et al. 2010). It still occurs very rarely in Venezuela and Colombia, and also southwards to Argentina and Chile (BirdLife International 2014). The greatest declines appear to be in the northern area of its range, namely Venezuela and Colombia (Beletsky Les 2006). Recently, it has been recorded as declining in Ecuador (Williams 2000), Peru, Bolivia, Colombia (BirdLife International 2014), and Venezuela (Cuesta and Sulbaran 2000; Sharpe et al. 2008). By contrast, it is more stable in Argentina (Pearman 2003), especially in the largest known population, which is in north-west Patagonia (Lambertucci 2010).

The Andean condor is considered near threatened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The factors for its rarity include foraging habitat loss, secondary poisoning from animals killed by hunters and direct persecution, the last factor due to the belief that it attacks livestock (Reading and Miller 2000; Roach 2004; Tait 2006; Rfos-Uzeda and Wallace 2007).

Similar to the policy for the California condor, from 1989 there have been reintroduction programs releasing captive-bred Andean condors from North American zoos into the wild in Argentina, Venezuela, and Colombia (Hilty and Brown 1986; Houston 1994; Chebez 1999; Roach 2004). Improvements may also be due to increased tourism in Chile and Argentina which showed the ecotourism value of the species and reduced persecution (Imberti 2003).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 220;