The Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus, Linnaeus 1758)

Physical appearance. The Egyptian vulture is also called the White Scavenger vulture or Pharaoh's Chicken and is the smallest of the Old World vultures. Despite its name, it is not found only in Egypt. Its range extends from the Cape Verde and Canary Islands, and Morocco in the West, across Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, to Northern Egypt and southwards to West and East Africa, including the Sahelian parts of Niger, northern Cameroon, Chad, northern Sudan and Ethiopia (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). In the north, it breeds in southern Europe, from Spain in the west, through the Mediterranean to Turkey. In Asia, it ranges from the Caucasus and central Asia to Northern Iran, Pakistan, northern India and Nepal (Cramp and Simmons 1980; Del Hoyo et al. 1994; Levy 1996; Angelove et al. 2013; BirdLife International 2014).

The three widely-recognized subspecies vary in size, with slight graduation due to migration, dispersal and intermixing. The mediumsized, nominate subspecies Neophron percnopterus percnopterus is found from Southern Europe to central Asia and northwestern India, and also in northern Africa south through Tanzania, into Angola and Namibia. The smaller Neophron percnopterus ginginianus occurs in Nepal and India (except for northwestern India). The largest, Neophron percnopterus majorensis is found in the Canary Islands, where it is may have been resident for more than 2000 years (Donazar et al. 2002a; Agudo et al. 2010). In the nominate species, the average length is 47-65 cm (19-26 in) from bill to tail. The weight is about 1.9 kg (4.2 lbs). The long, slender bill is dark grey. N. p. majorensis is about 18 percent larger in body mass, with a weight of 2.4 kg (5.3 lb) (Donazar et al. 2002a,b). N. p. ginginianus is 10 to 15 percent smaller than N.p. pernopterus, as males are 47-52 cm (19-20 in) long and females are 52-55.5 cm (20-21.9 in) long (Rasmussen and Anderton 2005). The bill is pale yellow. The wingspan is about 155 to 170 cm (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Donazar et al. 2002a).

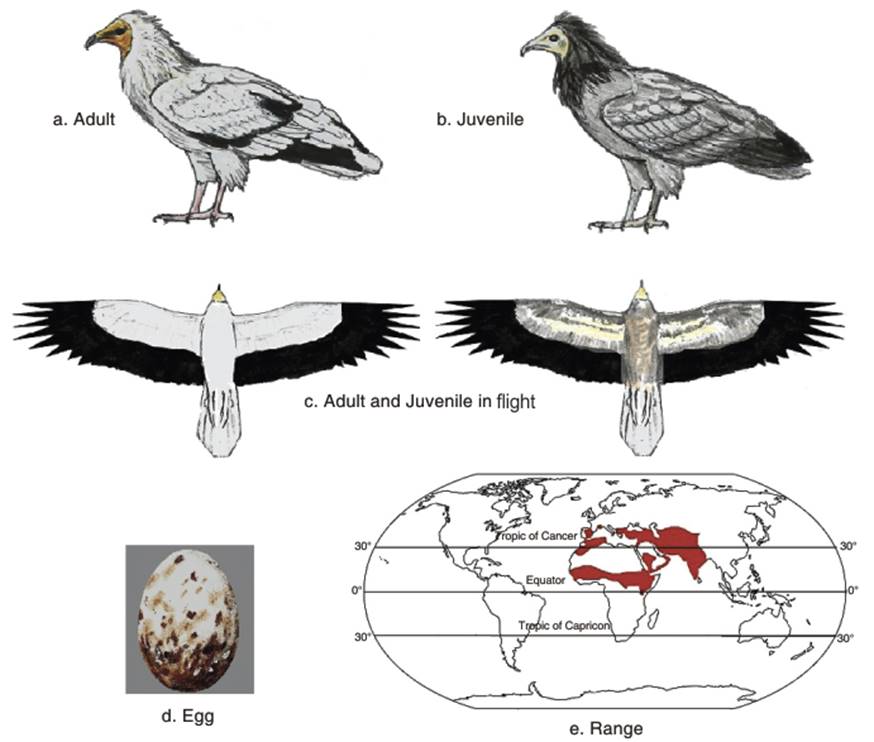

The face and bill base are yellow in both sexes, but males may have deeper orange skin during the breeding season. The feathers of the neck are long. The tail in flight is wedge shaped and the primaries and secondaries are black, contrasting with the white underwing coverts and white centres to the primaries above. The wings are pointed and the legs are pink in adults, but grey in juveniles. Females are slightly larger than males. Juveniles are brownish black to brown, patched with black and white, until they attain adult plumage at five years (Ali and Ripley 1978; Clark and Schmitt 1998; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001) (Fig. 2.1 a,b,c).

Fig. 2.1. Egyptian Vulture

Classification. The Egyptian vulture is the only member of the Genus Neophron (Savigny 1809). This genus is recorded as the oldest branch within the evolutionary tree of vultures (Wink et al. 1996). Regarding the different subspecies within the species of Neophron percnopterus, Kretzmann et al. (2003) used microsatellite loci to determine the genetic difference between the sedentary populations on the Canary and Balearic Islands and the migratory populations on the Iberian Peninsula. This and other studies examining both molecular and morphological differences discovered the new subspecies N. p. majorensis, proving limited gene flow between Canarian and other populations (Donazar et al. 2002a). Donazar et al. (2002a) note that the morphological differences between N. p. majorensis and N. p. percnopterus in western European and African populations (including Cape Verde Islands) are as significant as those between the subspecies ginginianus and percnopterus in Central Asia.

In addition to the three subspecies mentioned above (i.e., Neophron percnopterus percnopterus, Neophron percnopterus majorensis and Neophron percnopterus ginginianus) two investigators named Nikolai Zarudny and Harms also described another possible subspecies, named N. p. rubripersonatus, from Baluchistan region in 1902. This was identified by a dark bill with a yellow tip and darker reddish-orange skin on the head (Hartert 1920). This coloration was not recognized as grounds for a different subspecies, but rather an intermixing of subspecies due to its intermediate coloration (Rasmussen and Anderton 2005).

The Egyptian vulture has also been studied within the evolutionary lineages of Old World vultures (Wink and Hedi Sauer-Gurth 2004). There are two main evolutionary lineages in Old World vultures (Wink 1995; Wink and Seibold 1996; Wink et al. 1998; Seibold and Helbig 1995). One assemblage, which 'shares many biological characters' includes the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) and the Bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) (Wink and Sauer-Gurth 2004: 489). The Bearded vulture is considered the nearest evolutionary relative of the Egyptian vulture, and the two are often placed together in the separate subfamily of the Gypaetinae (Seibold and Helbig 1995).

There are three Genera in this subfamily: Genus Neophron for the Egyptian vulture, Neophron percnopterus; Genus Gypaetus for the Lammergeier or Bearded vulture; and Genus Gypohierax for the Palm-nut vulture. The second lineage includes the genera Gyps and Necrosyrtes which are a monophyletic clade with Sarcogyps and Aegypius/Torgos/ Trigonoceps, and Sarcogyps. The first group appears physically different as, while the second group have downy or bare heads, the Egyptian, Bearded and Palmnut vultures have feathered necks and for the latter two, the heads are also feathered (Wink and Sauer-Gurth 2004).

Foraging. The Egyptian vulture is ecologically adaptable, eating carrion, faeces, waste, insects and eggs. It lives mainly in open arid and rugged landscapes (Donazar et al. 2002b). It is usually marginalized by the larger vultures at a carcass, due to its small size. Consequently, it feeds after the larger birds have opened the carcass and consumed most of the flesh, leaving small morsels for the pickers (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

Egyptian vultures, similar to some other Old and New World vultures, roost communally (Ceballos and Donazar 1990). Roosts have been reported throughout the entire range of the species (Brown and Amadon 1968; Cramp and Simmons 1980). Roosting trees include the European white poplar (Populus alba L.). A study by Ceballos and Donazar (1990) in northern Spain using fecal pellets in roosting areas found the principal food species to be European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus, Linnaeus 1758), domestic cat (Felis catus, Linnaeus 1758), domestic dog (Canis familiaris Linnaeus 1758), European badger (Meles meles, Linnaeus 1758), red fox (Vulpes vulpes, Linnaeus 1758), domestic horse (Equus caballus, Linnaeus 1758), domestic and wild pig (Sus scrofa, Linnaeus 1758), domestic cattle (Bos primigenius, Bojanus), domestic sheep (Ovis aries, Linnaeus 1758) and domestic goat (Capra aegagrus hircus, Linnaeus 1758).

The preponderance of each species was linked to the seasonal changes in the death rate of these mammals due to disease. There was also much plant matter in the food, mostly the stems and seeds of both cultivated and wild plants, e.g., watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai), cherry (Prunus avium (L.) L. 1755) and melon (Cucumis melo L.). Most of the plant material was associated with wool and hair, as the plant matter was eaten to aid pellet formation (Ceballos and Donazar 1990).

Breeding. Typically the Egyptian vulture nests on ledges or in caves on cliffs (Sara and Di Vittorio 2003). Nest sites were on huge boulders, and ledges, crevices and caves on cliffs in Turkey (Vaassen 2000), Israel (Shirihai 1996), the Canary Islands (Clarke 2006), the Cape Verde Islands (Clarke 2006) and Eritrea (Smith 1957). Donazar et al. (2002b) record breeding in the Canaries Islands taking place in holes in cliffs of variable size. Angelove et al. (2013: 141) in study in Oman, found that all the recorded nests were 'in holes or crevices on very steep slopes or cliffs that had an abundance of potential nesting cavities', these being located 'high up (mean elevation 119 m, n = 32) on ridges and hills that were remote from human habitation.' Also favored are cliffs located near the bottoms of valleys (Bergier and Cheylan 1980). This may be due to 'the necessity of minimizing the energy investment in finding and carrying food to the nest', as this species carries food to the nest in its beak, 'so for the small amount it is able to carry long trips may not be worthwhile' (Cerballos and Donazar 1989: 358). Cerballos and Donazar (1989: 358) further record that 'the placement of nests at the bottom of valleys shows that the Egyptian vulture is a species notably tolerant towards human activities, a factor which has an extremely variable effect on other species.'

Records exist of wider choices in nest locations, especially in the past when the population of this species was much higher. Rarely, ground nesting is recorded. 'To our knowledge, there are three published records on pairs occupying ground nests under extreme conditions' (Nikolov et al. 2013: 418). One was in the Canary Islands, where two cave nesters moved to flat shrubland, reared a juvenile and returned to cave nesting the next year (Gangoso and Palacios 2005). Another case was on the Island of Farasan, in the Red Sea near Saudi Arabia, where a pair nested in an old Osprey Pandion haliaetus nest (Jennings 2010). The third case was in India, where there was a nest at the base of a tree (Paynter 1924).

Other nesting sites are in towns and even the Egyptian pyramids (see also Heuglin 1869; Nikolaus 1984; Baumgart et al. 1995; Nikolov et al. 2013). Tree nesting was recorded in India, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and Oman (Butler 1905; Archer and Godman 1937; Gallagher 1989; Naoroji 2006). Other records include those of Wadley (1951) who described a breeding colony of forty birds in trees from 1943 to 1946 in Western Turkey; and also those of (Prostov 1955) near the village of Veselie, and of Arabadzhiev (1962) near the town of Yambol, both in Bulgaria (Nikolov et al. 2013). In northern Spain, many birds nested in pines (Aleppo Pine, Pinus halepensis Miller; Scots Pine, P. sylvestrics L. and European Black Pine, P. nigra J.F. Arnold). Ceballos and Donazar (1990: 23) note that 'The choice of pines for roosting may only be a consequence of abundance in the study area and of the fact that pines in Spain reach taller heights than broad-leafed trees.'

The egg-laying period varies in different countries. In Spain it was from March to April (Ceballos and Donazar 1990). In Georgia, eggs were laid in the first half of April (Gavashelishvili 2005), in Armenia May to June (Adamian and Klem 1999), in Israel from March to April (Shirihai 1996), in the Canary Islands February to mid-April (Clarke 2006), the Cape Verde Islands from November to April (Clarke 2006), Morocco from late March to early May, starting with desert areas (Thevonot et al. 2003); in Algeria in late March to late April (Heim de Balsac and Mayaud 1962); in Tunisia from late March to late April (Heim de Balsac and Mayaud 1962; Isenmann et al. 2005); and in Saudi Arabia during the first few months of the year (Jennings 1994, 1996). Angelove et al. (2013: 143) reported that vultures on Masirah Island, Oman laid eggs October-March (n = 25), with most laying in January and February. They however speculate on the possibility that there would be a laying period May-September, 'but the timing of our surveys precluded determining this.'

The records for Africa are more scanty, however in Eritrea and Ethiopia, eggs were laid in the months of January to May, and October to November (Ash and Atkins 2009). In Somalia, laying took place from January-April (Archer and Godman 1937; Ash and Miskell 1998). In Uganda, laying occurred from October to December (Carswell et al. 2005). In South Africa, the critical months are August to November or December, beginning with the spring rains (Brooke 1982; Simmons and Brown 2006a).

'The Egyptian vulture is, with the Lammergeier Gypaetus barbatus, the only vulture whose clutch usually has two eggs' (Donazar and Ceballos 1989: 217). In about 70% of breeding attempts, one chick survives (see Cramp and Simmons 1980; Del Hoyo et al. 1994). Eggs are oval to round oval, rough dull white, dark orange-brown spotted and streaked eggs (Fig. 2.1d) (Isenmann et al. (op cit.) Heim de Balsac and Mayaud 1962; Shirihai 1996; Adamian and Klem 1999). The incubation periods and nesting duration vary. For example, in Armenia the incubation period was 42 days and the nesting period 69 to 90 days (Gavashelishvili 2005). In Israel it was 39 to 45 days, and the nesting period 70 to 90 days (Shirihai 1996).

Population status. The distribution of the Egyptian vulture is shown in Fig. 2.1e. Some populations, however have remained stable or slightly increased; for example in Spain (Del Moral 2009; Kobierzycki 2011; Yemen (Porter and Suleiman 2012) and Oman (Angelove et al. 2013). Egyptian vulture populations have declined across its wide range, especially outside Spain, in the Mediterranean islands (e.g., Cyprus, Greece, Crete and Malta, and in the southern parts of Africa and Central Asia (Mundy et al. 1992; Tucker and Heath 1994; Levy 1996; Xirouchakis and Tsiakiris 2009; Angelove et al. 2013). In the Macaronesic archipelagos off the Western European and northwestern African coasts, it declined from common status during the latter part of the twentieth century (Bannerman 1963; Bannerman and Bannerman 1968). It is also extinct or very rare from several islands in the Canary Islands (Martin 1987; Delgado 1999), with reduced populations only on the islands of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote 1980 (Palacios 2000).

The Canary population is particularly important, due to its reclassification as a new subspecies (N. p. majorensis) (White and Kiff 2000; Donazar et al. 2002b). In the Canaries, as in some parts of Western Europe, the reasons for the population decline have been described as 'illegal persecution, poisoning, electrocution, habitat destruction and reduction of food supplies' (Donazar et al. 2002b: 90). These authors note that in the Canaries at least Egyptian vultures seem frequently to select power lines for roosting, making them 'extremely vulnerable to accidents by collision or electrocution' (p. 95).

Egyptian vultures in temperate Europe migrate to Africa during winter, mostly avoiding large water bodies (Spaar 1997; Yosef and Alon 1997). In Italy, they migrate through Sicily and the islands of Marettimo and Pantelleriato to Tunisia (Agostini et al. 2004). In the Iberian Peninsula, they migrate across the Strait of Gibraltar to North Africa, and others move south through Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Israel (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Meyburg et al. 2004; Garcia-Ripolles et al. 2010).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 223;