White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis (Burchell 1824)

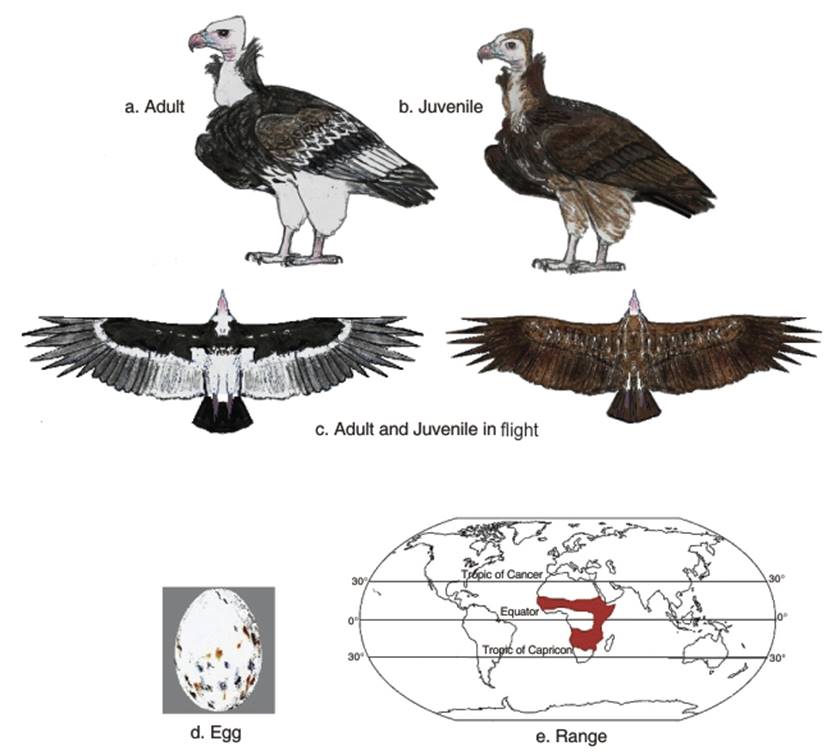

Physical appearance. The White-headed vulture is a medium-sized vulture, 72-85 cm (28-34 in) in length and a wingspan of 207-230 cm (82-91 in). Females are slightly larger than males; they usually weigh around 4.7 kg (10.4 lbs), while males weigh 4 kg (8.8 lbs) or less. It has a rear-peaked, downy white topped head with pinkish skin, with a large dark tipped red bill and blue cere, a black collar ruff, ruffed white legs, and a black feathered breast. The female has white inner secondaries, but in the male they are grey. In the juvenile, the plumage is dark, with a white head and white edges to wing linings similar to those of the adult (Ferguson-Lees and Chrsitie 2001; BirdLife International 2013) (Fig. 2.4 a,b,c).

Fig. 2.4. White-headed Vulture

Classification. Wink (1995) classifies this species with the clade Aegypius complex (Aegypius, Torgos, Trigonoceps and Sarcogyps). Snow (1978) noted that the White-headed vulture has similar morphological similarities to the Asian Red-headed vulture (Sarcogyps calvus), despite the neck wattles of the latter species and considered the possibility of merging the two genera Trigonoceps and Sarcogyps. This species is often described as eagle-like. For example, Hancock (2013) (Birdlife of Botswana) writes 'On a continuum from predatory eagles to scavenging vultures, the White-headed vulture sits near the middle, rubbing shoulders with its larger relative the Lappetfaced vulture on the one side, and the Bateleur on the other.'

Foraging. The White-headed vulture is the most solitary forager among the African vultures, a loner, often the first at a carcass, or feeding alone on small carcasses (Steyn 1982). Ash and Atkins (2009) taking a case study of foraging birds in Ethiopia, recorded 56% flying single, 24% in pairs, 18% in small groups of 2-5 birds, and only once in a large group (10 individuals). Dowsett et al. (2008) in Zambia and Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett (2006) in Malawi also report only individuals or small groups of three or four appear at carcasses, unlike the social Griffon vultures. The distribution of this species is also related to its main nesting tree, the Baobab Adansonia digitata (Palgrave 1977). However, preferred habitats include lightly wooded savanna, bush savanna, montane forest-grassland mosaic, mixed deciduous and broadleaved woodland in low elevations, and even semi-desert (Mundy et al. 1992; Penry 1994; Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett 2006; Dowsett et al. 2008; Ash and Atkins 2009; Borrow and Demey 2010). It is occasionally recorded in the arid thornveld areas of western Etosha National Park in Namibia and the Kalahari (Mundy 1997). It is usually rare near dense forests, human habitation and cultivation (Penry 1994; Dowsett et al. 2008).

Reinforcing its eagle-like status, the White Headed vulture predates lizards, snakes, insects, even mongooses, piglets and possibly Queleas quelea quelea (Linnaeus 1758) and occasionally takes the prey of other avian predators (Attwell 1963; Biggs 2001a,b; Dowsett-Lemaire 2006; Dowsett et al. 2008). Despite its slightly smaller size, it is usually dominant over single White-backed vultures, but can be driven away by flocks of the species (Mundy 1997). In a study in Botswana, Herremans and Herremans- Tonnoeyr (2000) found the foraging patterns of the White Headed vulture more similar to the Wahlberg's Eagle Aquila wahlbergi and steppe eagle A. nipalensis, which foraged in both conservation areas and unprotected land, rather than those of the other vultures, which clustered at the interface between conservation areas and unprotected land.

Breeding. The White-headed vulture is a non-colonial nester; individual nests may be up to 8 to 15 km apart, in the crown of tall, usually solitary baobab or acacia trees (e.g., Acacia nigrescens). Its distribution is closely linked to that of the baobab (Palgrave 1977; Irwin 1981; Dowsett-Lemaire 2006; Hartley and Hulme 2005).

Different breeding dates have been recorded in different countries. It usually lays one egg (Dowsett et al. 2008) (Fig. 2.4d). For example, in Ethiopia, egg-laying was reported from October to December (Ash and Atkins 2009), while in Somalia the breeding season was from late October to March, with most of the egg laying occurring in December and January (Ash and Miskell 1998). In Uganda, there are variable egg-laying dates recorded; for example April (1949 and 1969), March 1964 and November 1949 (East Africa Natural History Society Nest Records) and also November and January (Kinloch 1956).

In Southern Africa, egg-laying occurs mostly in the winter (i.e., May to July) (Mundy et al. 1992, 2008). In Zambia, egg-laying was documented from May to October, with the largest number of records for June and July (Dowsett et al. 2008). Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett (2006) gave examples of nesting in May and August in Malawi. In Namibia, there are two records for June and July (Jarvis et al. 2001). In Bostwana, there are records from August (Penry 1994) and May to July (Skinner 1997). In Zimbabwe, egg-laying dates from June, July and August (Irwin 1981; Hartley and Hulme 2005).

Population status. The distribution of the White-headed Vulture is shown in Fig. 2.4e. The evidence points to a small population in a large range within sub-Saharan Africa generally outside the dense forest and human habitation (from Senegal, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau east to Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, and south to easternmost South Africa and Swaziland) (Harrison et al. 1997). The population of White-headed vultures has declined in West Africa from the 1940s (Hall 1999; Thiollay 2006a,b,c, 2007a,b, 2012), and is currently declining in East Africa (Virani et al. 2011). In southern Africa, it now occurs mostly in protected areas. Hancock (2008a) reported that it was the rarest vulture recorded in a survey of Botswana. Other depressing news concerns Niger (Brouwer 2012) and Mozambique (Parker 2005a).

Factors for the reduction in the populations of White-headed vultures include reduced populations of medium and large wild ungulates, habitat conversion, indirect poisoning (poisoned carcass baits to kill jackal predators of small livestock, and for lions and hyenas that kill larger livestock), secondary poisoning from carbofuran, exploitation for the international trade in raptors, killings for traditional medicine (especially in South Africa) and high human presence disturbing breeders (Mundy et al. 1992; Hall 1999; Genero 2005; Baker 2006; Davies 2006; Simmons and Brown 2006b; Hancock 2008; Otieno et al. 2010; Kendall 2012). There is also a potential threat from the use of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac for veterinary purposes, which fatally affects vultures (BirdLife International 2007; Woodford et al. 2008). For these reasons, this species is commoner in protected areas in southern and East Africa (Dowsett-Lemaire 2006).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 216;