Lammergeier or Bearded Vulture, Gypaetus barbatus (Linnaeus 1758)

Physical appearance. The Bearded vulture, also known as the Lammergeier or Lammergeyer, is the only species of Genus Gypaetus. It is a very large vulture, rivalling the Cinereous vulture and the Himalayan Griffon vulture in size. In length, it is 94-125 cm (37-49 in), and weighs 4.5-7.8 kg (9.9-17.2 lb) with a wingspan of 2.31-2.83 m (7.6-9.3 ft). Two subspecies have been identified, G. b. barbatus the nominate, slightly larger subspecies from Eurasia and North Africa (weighing 6.21 kg or 13.7 lb); and G. b. meridionalis weighing 5.7 kg (13 lbs) from south of Tropic of Cancer in southwestern Arabia and East and southern Africa (Mundy et al. 1992; Kruger et al. 2013). Some of the largest specimens of G. b. barbatus are found in the Himalayan mountains (Hiraldo et al. 1984; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

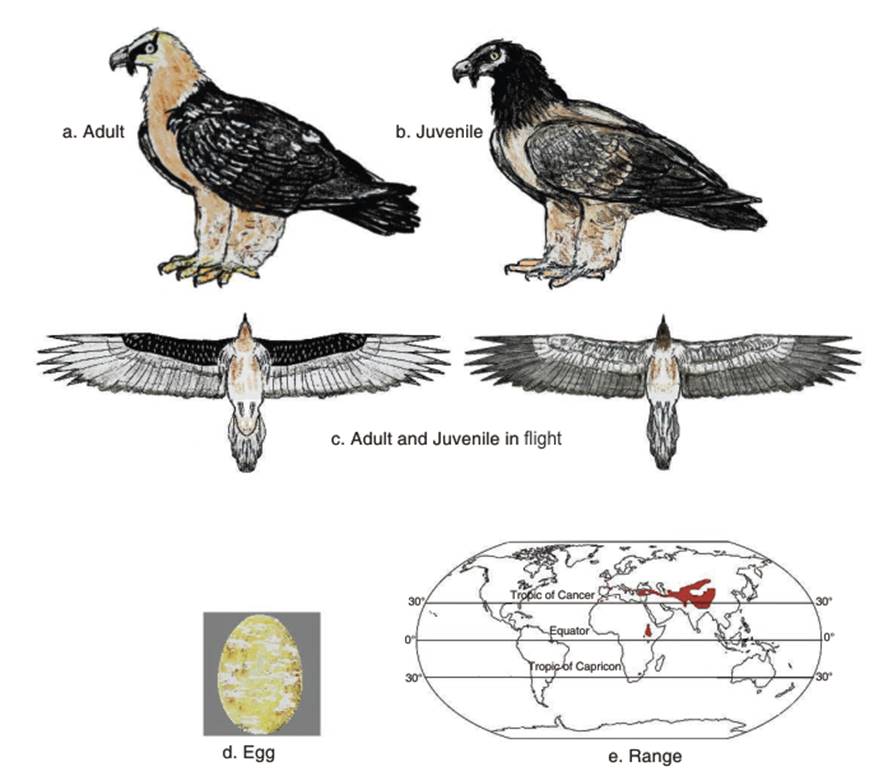

In coloration, Bearded vultures have light buff colored feathers on the head and body, with dark brown to blackish back and upper wing feathers. The underside of the wings are also dark blackish brown, and the primaries are greyish. The tail feathers are blackish to dark brown. The head, breast and leg feathers may be orange, possibly due to dust-bathing, mud-rubbing or drinking in mineral-rich waters. The juvenile bird is dark black-brown over most of the body, with a buff-brown breast (Fig. 2.7 a,b,c). It is five years before it acquires adult plumage (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). Brown (1977) describes juveniles of the African subspecies G.b. meridionalis as having a blackish brown head, a paler dull brown breast and belly, and dark brown, pale streaked upper sides. Later, in the more mature subadult, more white feathers grow on the crown and cheeks, and a dark chestnut neck-ring separates the head from the paler, more reddish breast and belly.

Fig. 2.7. Bearded Vulture

Classification. As mentioned above, there are two recognized subspecies of the Bearded vulture. It has been argued that this is not a true vulture (see Amadon and Bull 1988); however whether or not it is a true vulture (depending on the definition of vulture), several studies using the nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene have classified the Bearded vulture with the Egyptian vulture as a sister species in a Neophron-Gypaetus clade that is separate and basal to other Old World vultures (Wink 1995; Siebold and Helbig 1995; Wink and Seibold 1996; Wink et al. 1998). Older studies using karyological (De Boer and Sinoo 1994), morphological (Jollie 1976), and embryological data (Thaler et al. 1986) had previously hinted at this conclusion. More recently, Lerner and Mindell (2005) used molecular sequences from one nuclear and two mitochondrial genes, and found that the Bearded vulture and the Egyptian vulture, although highly divergent, are more closely related to each other than to other Accipitridae species. Hence, these two species share a clade called Gypaetinae, including the Palm-nut vulture and possibly the Madagascar Serpent Eagle (Eutriorchis astur, Sharpe 1875).

Regarding the Bearded vulture subspecies, G. b. barbatus and G. b. meridionalis, research based on phylogenetic analysis of DNA from museum specimens from the Western Palearctic found two divergent mitochondrial lineages, one (lineage A) occurring mainly in western European populations and the other (lineage B) in African, eastern European, and central Asian populations (Godoy et al. 2004). The results also showed that while the two lineages were situated in two different regions, there was marked expansion and mixing especially by the lineage B through central Europe and North Africa, with most of the mixing in western regions of the Alps and Greece. A third subspecies. G.b. haemachalanus was not fully recognized (Brown and Amadon 1968; del Hoyo et al. 1994).

Foraging. The Bearded vulture is a scavenger, but is the only scavenger that prefers bone marrow to meat; bone marrow comprises 85-90% of its diet (Boudoint 1976; Hiraldo et al. 1979; Brown 1988; Margalida and Bertran 2001; Ferguson- Lees and Christie 2001). It has a powerful digestive system, including acids with a pH of about 1, for dissolving bones (Brown and Plug 1990; Houston and Copsey 1994). Bones too large to be swallowed [e.g., over 4 kg (8.8 lbs) are broken for their internal marrow by carrying them in flight to a height of over 50 m (160 ft) and dropping them onto rocks below]. This requires several years' practice by juveniles.

They may also break small bones by beating them against rocks using the bill. Margalida et al. (2009) record sheep and goats as comprising 61% of the prey remains identified in the Pyrenees. Domestic livestock were 73% of their diet in the Pyrenees and 80% in southern Africa (see also Brown and Plug 1990). Margalida et al. (2009: 240) also note that 'although the Bearded Vulture is considered a bone-eating species, our results suggest that during the breeding season, small dead animals (i.e., prey with a high meat content) are very important prey when parents are feeding young nestlings.'

Particular food preferences were also noted (Margalida et al. 2009), which were not proportionate to their availability. Larger species' bones were generally avoided, possibly because of the greater energy expenditure required for transporting and digesting these larger bones (see also Margalida 2008a, 2008b). The ideal species in terms of size and weight were sheep Ovis aries Linnaeus 1758, goats (Capra aegagrus hircus Linnaeus), 1758 or Southern Chamois Rupicapra rupicapra Linnaeus 1758. The commonest anatomical part favored by Bearded vultures are sheep limbs (Margalida et al. 2007a), the most nutritious part of the sheep limb being the fat content of the extremities (Margalida 2008b).

In the study by Margalida et al. (2009), there was no relationship between the percentage of Ovis/Capra in the diet and the presence of feeding stations supplied with sheep limbs. This demonstrated that Bearded vultures took sheep irrespective of the presence of feeding stations. One fact justifying this assessment was that feeding stations were principally used by the non-breeding population (Heredia 1991; Sese et al. 2005; Margalida et al. 2009).

These authors also found that during the first month of breeding, adults selected prey items with higher meat biomass (possibly indicating a link between meat consumption and breeding success). This was also linked to a lowered use of the bone breaking sites (termed ossuaries) during the first month of the chick's life (see also Margalida and Bertran 2001). Speculatively, areas with limited meat availability and inexperienced adult foragers, might be linked to the breeding failures that are commoner during the hatching and chick-rearing periods (Margalida et al. 2003). Of course, other factors such as weather, human pressure and parent quality may play a role in breeding success (Margalida et al. 2009).

Bearded vultures also eat living tortoises (Testudinidae, Batsch 1788); these are killed by the same method as bone-breaking; they are carried to a height and dropped on to rocks below. Other species killed in this way include rock hyraxes Procavia capensis (Pallas 1766), hares (Genus Lepus, Linnaeus 1758), marmots (Genus Marmota, Blumenbach 1779) and monitor lizards (Genus Varanus, Merrem 1820). Mammals killed on the ground, usually young animals (some driven off cliffs, perhaps accidently) include ibex and wild goats (Genus Capra, Linnaeus 1758), Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra, Linnaeus 1758) and (R. pyrenaica, Bonaparte 1845) and Steenbok (Raphicerus campestris, Thunberg 1811) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

The range of the Bearded vulture encompases cliffs, crags, precipices, canyons, gorges and inselbergs, in mountainous areas. The vegetation of these areas includes forest clumps, high altitude steppe, alpine pastures and meadows and montane grassland and heath. These high altitude habitats are usually above 1,000 m (3,300 ft). Most birds are recorded above 2,000 m (6,600 ft), near or above the tree line, i.e., up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in Europe, 4,500 m (14,800 ft) in Africa and 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in central Asia (Ferguson- Lees and Christie 2001; Gavashelishvili and McGrady 2006a,b, 2007; Kruger et al. 2006). For food, they also require the presence of predatory birds and mammals, such as Golden Eagles and wolves, as these animals kill animals and therefore provide the bones upon which the Bearded vulture feeds. Other feeding areas have also been recorded. For example, in Ethiopia, Bearded vultures are reported at refuse dumps near human settlements, feeding on dead animals and human organic discards (Brown 1977).

Breeding. The Bearded vulture is generally a solitary nester, usually building large stick nests on sheltered ledges of rock cliffs. There are regional variations in nesting. For example, in Iraq, a nest was located on a cliff 2,400 m high (Ararat et al. 2011). Abuladze (1998) writes that nests in Caucasia (parts of Georgia and Russia) were recorded at altitudes ranging from 815 to 2200 m, with the greatest number (76%) of nests found between 1500 and 1900 m above sea level. In another study in Russia, nests were also located on cliffs, but mostly in narrow ravines near rivers, with an average height of 113 m and a range of 10-250 m (Karyakin et al. 2009). In Russia, nests were large in some cases, up to 2-3 m high, and also small in some cases, about 40 cm high. The main determinant was the availability of branches and sometimes bones and animal hide (Karyakin et al. 2009). In the Spanish Pyrenees, nests were recorded as near the midpoint of cliff faces (Donazar et al. 1993). On the Mediteranean island of Corsica, nests were observed at variable elevations, as low as 10 metres above the ground and as high as 200 m, but all were inaccessible at least to people (Grussu 2008). Nearby, in Sardinia, an old nest was located only 4.5 m high in a calcareous cliff surrounded by oaks (Genus Quercus L.) and junipers (Juniperus L.) (Grussu 2008). Also in the Mediteranean, in Crete, nests were built on cliffs facing either the east or south (Vagliano 1984).

The clutch size is usually 1 or 2 light brown or pink, brown spotted eggs (Barrau et al. 1997; Karyakin et al. 2009) (Fig. 2.7d). While several authors describe the clutch as of one egg, Margalida et al. (2003) report that 80% of the clutches comprised two eggs. Generally, the incubation period is 55-60 days and the nestling period is about 105-112 days (Tarboton 1990; Shirihai 1996).

There are regional differences for the egg laying period. In Asia, for example, in the Altai and Tuva regions, nesting begins in January, and chicks fledge in July (Karyakin et al. 2009). In Armenia, most egg laying starts in January (Gavashlishvili 2005). However, Adamian and Klem (1999) report that a young bird about 35 days old was seen in a nest in May 1994. Abuladze (1998: 179) noted that most eggs are laid 'in the first half to middle of January', while hatching takes place early to mid-March and fledgling in the second half of June to the beginning of July. In Israel, the breeding season started in mid-December and ended just before June (Shirihai 1996). In Greece and Macedonia, eggs were laid from December to early February (Reiser 1905; Grubac 1991; Handrinos and Akriotis 1997).

In Europe, in the eastern Pyrenees, Margalida et al. (2003) record the average laying date as January 6 (with a range from 11 December to 12 February) and no significant annual differences. Hatching averaged between 21 February and 3 March and fledgling in May to July.

Concerning Africa, Kruger et al. (2013: 1) note that 'within sub-Saharan Africa, knowledge of the species is poor.' There are two records from Africa: in Uganda, eggs were laid in October and November (Urban and Brown 1971) and December 1949 (EANHS Nest Records).

Population status. The population distribution of the Bearded vulture is shown in Fig. 2.7e. In past decades, the Bearded vulture was described as commonest in Ethiopia. Brown (1977: 50) writes that this species was 'Common, locally abundant' and that 'There is thus no question that the Lammergeier is relatively common in Ethiopia, perhaps more so than anywhere else in the world except Tibet' (Schaefer 1938 is cited in reference to Tibet). In addition, it was 'most numerous around towns and villages, but also numerous in high mountains' and present in most of East and South Africa (ibid.). On reason was noted: 'in Ethiopia, the fact that immatures can readily find scraps of meat, skin, and bones around any village rubbish dump or slaughter house improve survival and helps to explain the apparently higher proportion of immatures in the Ethiopian than in the Lesotho or Spanish populations' (ibid. 52). In Europe, it nearly reached extinction by the early twentieth century, due to hunting and habitat modification. It was believed to kill lambs and sheep (hence the German name Lammergeier or Lamergeyer) and sometimes falsely, kill even children (Everett 2008).

More recently, the Bearded Vulture is recorded as rare and locally threatened, despite its extremely wide range and its natural tendency to sparse, wide ranging populations. It is still commoner in Ethiopia, with populations in the Himalayas. Despite near extinction in Europe by the early 20th century, it is now considered endangered in Europe, 'with fewer than 150 territories in the European Union in 2007' (Margalida 2009: 236). Reintroductions have been undertaken in southern Spain (Andalusia), the Alps (France, Austria, Switzerland and Italy) and Sardinia in the Mediterranean Sea, with possible future projects in the Balkans (Margalida 2008).

These reintroductions have had moderate success, especially in the Pyrenees mountains of Spain, the Swiss and Italian Alps, and parts of France. The largest population is in the Pyrenees, but here there are two major problems that compromise the birds' recovery: a decline in productivity (Carrete et al. 2006) and increased illegal poisoning (Margalida et al. 2008c). To counter these problems, the population in the Pyrenees is supported using feeding stations for enhanced breeding success and mortality reduction, especially in the pre-adult population (Heredia 1991; Margalida et al. 2009). Problems include poisons for carnivore-baiting, habitat modification, human disturbance of nesting birds and electrocution and collisions with powerlines (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 241;