The Black Vulture Coragyps atratus (Bechstein 1793)

Physical appearance. The Black vulture is also known as the American Black vulture, to distinguish it from the much larger and unrelated Eurasian Black vulture. Its length from bill to tail measures 56-74 cm (22-29 in). The wingspan is 1.33-1.67 m (52-66 in). The weight varies from smaller figures for vultures from the tropical lowlands of South America [(1.18-1.94 kg (2.6-4.3 lbs)] to those from North America and the Andes which range from 1.6-2.75 kg (3.5-6.1 lbs) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). The plumage is glossy black. The wrinkled skin of the featherless head and neck is dark grey (Terres 1980). The legs are greyish white (Peterson 2001). Unlike all the Old World vultures, the nostrils are perforate (undivided by a septum, so one may see through the bill from one side to the other) (Allaby 1992).

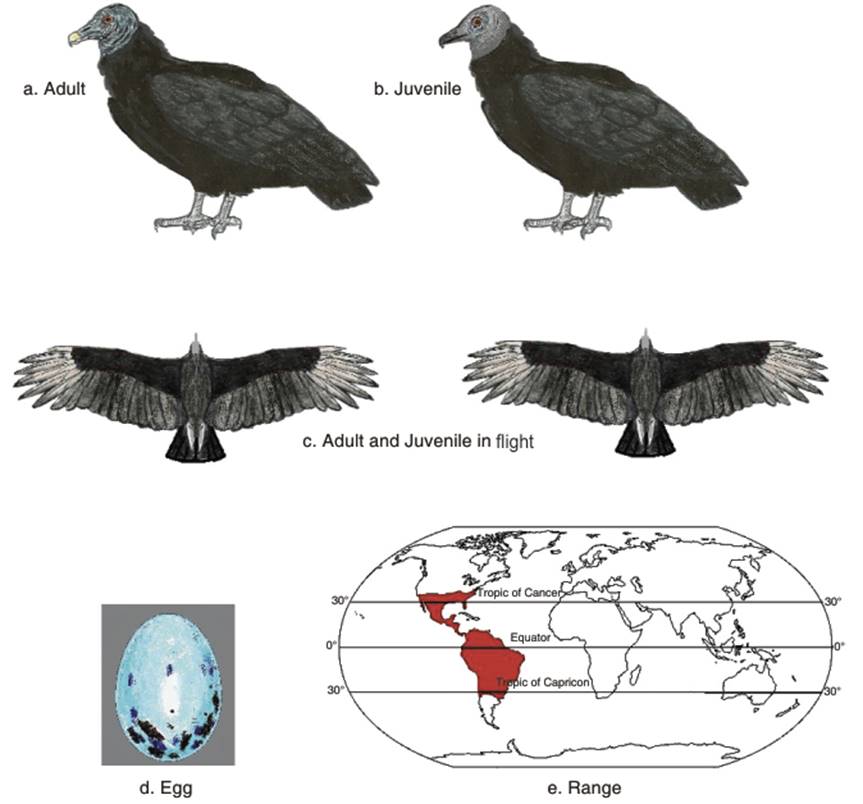

The wings and tail are broad and comparatively short, compared to those of the Turkey vulture (Fig. 3.1 a,b,c). In flight white underside wing patches are visible, due to the white bases of the primary feathers (Terres 1980). Occasionally, white individuals may occur; one such individual was seen in Pinas, Ecuador. It was a leucistic Coragyps atratus brasiliensis (Leucism is characterized by reduction in all types of pigmentation, unlike albinism which is caused by a reduction of melanin). This bird was described as white, but was not a full albino, as the tarsus and tail as well as some undertail feathers were black and the skin was the normal dark grey color.

Fig. 3.1. Black Vulture

The common bird that may be confused with the Black vulture is the Turkey vulture, with which it occurs throughout most of its range. Taylor and Vorhies (1933) gave an incisive way to distinguish the two species: the Black vulture has a blackish rather than reddish head color; in flight, it is stockier than the Turkey vulture, with shorter, broader wings and a shorter, square tail; also the leading edge of the Black vulture's wing is straighter and less curved than the wing of the Turkey vulture. The primaries do not show separate feathers as in the Turkey vulture; there are white patches on the terminal third of the Black vulture's wings, easily visible in flight, while the turkey vultures wing primaries and secondaries are silvery grey. The Black vulture flaps its wings more, sometimes flapping six to nine times before a glide, while the Turkey vulture soars, with only occasional wing beats.

Classification. Three subspecies of the Black vulture have been recognized, with size increasing from south to north (Wetmore 1962). The North American Black vulture (Coragyps atratus atratus), the nominate subspecies, occurs from the eastern United States to northern Mexico. It was named by the German ornithologist Johann Matthaus Bechstein in 1793. The Andean Black vulture (Coragyps atratus foetens) is similar in size to the North American bird, but has a slightly darker plumage, as the white wing markings are smaller and the underwing coverts are darker. It occurs in western South America and the Andes mountains. It was named by Martin Lichtenstein in 1817. The South American Black vulture (Coragyps atratus brasiliensis) is smaller, with lighter underwing color than the other two subspecies and occurs from southern Mexico southwards into Central America, Peru, Bolivia, southern Brazil and eastwards into Trinidad (Wetmore 1962, 1965). It was named by Charles Lucien Jules Laurent Bonaparte in 1850. This species is generally regarded as monotypic (i.e., having a common ancestor, despite the differences among the subspecies (Monroe 1968).

Foraging. The Black vulture is common, foraging in most areas, including urban and cattle grazing areas, except heavily forested areas (American Ornithologists' Union 2010). It is generally more abundant around towns and refuse dumps than in natural habitats. It also occurs in lowland and degraded and moist forests, shrub/grasslands and swamps, pastures, and heavily degraded former forests and is rare in mountainous areas (Peterson 2001). By its feeding habits, its nearest equivalent among the Old World vultures would be the Hooded vulture, or in the past some behavorial characteristics of the formerly common White-rumped vulture in urban areas.

It is both a solitary and communal forager, sometimes occurring in flocks of hundreds, especially near urban rubbish dumps. Carrate et al. (2009) in a study of a mixed case study in Argentina, note that the Black vulture is not sensitive to habitat fragmentation, less so than the Turkey vulture. In Guyana, the main habitats are scrub or brush habitats, including white sand scrub, bush islands, and dense, low second growth; also habitats altered by humans, such as gardens, towns, roadsides, agricultural lands, disturbed forests and forest edge (Braun et al. 2007: 10).

The Black vulture locates food by sight as their sense of smell is either minimal or absent. It also follows other New World vultures (Genus Cathartes—Turkey Vulture, the Lesser Yellow-headed vulture, and the Greater Yellow-headed vulture) as these species are able to forage by scent, detecting ethyl mercaptan, the gas emanating from decayed flesh, and hence detect carrion below the forest canopy. Aggressive Black vultures may dominate the Turkey vultures (Gomez 1994; Muller-Schwarze 2006; Snyder and Synder 2006). It has been described as variably dominant over the Turkey vulture and the two Yellow-headed vulture species when feeding at a carcass. Some authors describe the Black vulture as dominant only when in large flocks of over 50 birds, otherwise the relationship is approximately even in one to one encounters (Wallace and Temple 1987).

The Black vulture is described as 'an example of a winning species positively responding to human transformations' (Carrete et al. 2010: 390; see also Carrete et al. 2009). These authors admit 'detailed studies on its large-scale geographic expansion are lacking' but the 'scarce information available shows how the species, once limited to highly productive tropical habitats, has progressively advanced until its current occupation of broad regions of North and nearly all of South America.'

Evidence of this range expansion may be seen in the literature with a date trend (Darwin 1839; Houston 1985, 1988; Tonni and Noriega 1988; del Hoyo, Elliot and Sargatal 1994; Buckley 1997; Schlee 2000; BirdLife International 2014). A determining factor is adaptation to food sources associated with human development, such as rubbish dumps, human discards, livestock and road kills (del Hoyo et al. 1994; Carrete et al. 2009). The consequence is that the Black vulture shares its range with all the other Cathartid vultures (Olden and Poff 2003). In the United States, the Black vulture is increasingly entering cities for foraging and roosting, creating problems for people (United States Department of Agriculture USDA 2003). It also roosts communally year-round, usually in trees, as a prelude to foraging (Rabenold 1983). Communal roosts are also recorded as enabling energy savings through thermoregulation, opportunities for social interactions, and a reduced risk of predation (Buckley 1998; Kirk and Mossman 1998; Devault et al. 2004).

This species has a wide range of food sources (Buckley 1999; Hilty 2003). Food sources include the carcasses of monkeys, coyotes and newborn calves (Lowery and Dalquest 1951; Sick 1993). Other sources include turtle eggs and fruits such as bananas, avocados, oil palm fruit, coconut flesh and even salt (Coleman et al. 1985). By location these include: oil palm fruit and coconut flesh in Surinam and Dutch Guiana (Haverschmidt 1947), sweet potatoes on Avery Island, Louisiana (Mcllhenny 1945), salt from a cattle field in Pennsylvania (Coleman et al. 1985), avocados and oil palm (Brown and Amadon 1968), coconut husks in Trinidad (Junge and Mees 1961); avocados, the soft meat of coconuts and the oily pulp covering certain palm seeds in Panama (Sick 1993); coyole palm fruit in Veracruz, Mexico (Lowery and Dalquest 1951); cattle, coyote and human excrement (Mcllhenny 1939; Coleman et al. 1985; Maslow 1986; Buckley 1996); and fresh vegetables and the excrement from several captive Galapagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus) at the zoological park in central Florida (Stolen 2003).

Other records include dead fish in Panama (Wetmore 1965); palm fruits in Brazil (Pinto 1965); the carcasses of cattle and horses, and refuse around human habitations in Argentina (di Giacomo 2005); competition with seabird colonies, for example on islands such as the Moleques do Sul, Santa Catarina (Sick 1993); and the successful competition against Greater Yellow-headed vultures for dead fish on at least eight occasions at Cocha Cashu, Peru (Robinson 1994). Some records also document the killing of live prey (Avery and Cummings 2004), such as birds (Baynard 1909), skunks and opossums (McIlhenny 1939; Dickerson 1983), turtle hatchlings (Mrosovsky 1971) and fish (Jackson et al. 1978) and livestock (Lowney 1999).

Breeding. Black vultures usually build no nests, but lay eggs on hard surfaces; for example on the surface in caves, tree or log hollows, in rock piles, in dense vegetation or even on high roof tops (e.g., on buildings in Sao Paulo, Brazil) (Sick 1993). Other examples are: a small cave in an escarpment in Oaxaca, Mexico (Rowley 1984); old churches in Antigua, Guatemala (Sclater and Salvin 1859); rock crevices in volcanic remnants, clumps of large rocks, cliff caves and cavities in Nispero (Manilkara chicle (Pittier) Gilly) trees in El Salvador (Dickey and van Rossem 1938; West 1988); house roofs in Costa Rica and bare rocks in a cave in Colombia (Todd and Carriker 1922); hollow trees and roots, and caves and cliffs in Trinidad (Williams 1922); between the buttresses of trees such as silk cotton tree (Ceiba pentandra L. Gaertn.) in Guyana; and in pita trees in La Jagua, Panama (Wetmore 1965).

In Brazil, reports show variable locations as well. While Oniki and Willis (1983) record four nests in tree hollows and a treefall in Belem, Sick (1993) records nests on building roofs, holes in tree roots and dead buriti palms. In Argentina, Di Giacomo (2005) recorded tree nests up to 6 to 7 metres above ground, located in holes in dead and living trees, living species including (Prosopis L. spp., Caesalpinia paraguariensis Parodi Burkart), Enterolobium contortisiliquum ((Vell.) Morong), Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco (Schltr.), Sideroxylon obtusifolium ((Roem. & Schult.) T.D. Penn), Schinopsis balansae (Engl.) and Albizia inundata ((Mart.) Barneby and J.W. Grimes).

The egg laying period varies regionally. Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2001) describe the breeding season as related to the latitude. In Florida, breeding starts as early as January, while in Ohio it could start in March. Argentinian and Chilean birds start egg-laying in September, but in northern South America, October is more common, and in Trinidad November is usual. In the United States, Brock (2007) recorded eggs in April and May and young chicks between May and July. In the Yucatan, Stone (1890) recorded a nest with eggs on 15 February. In El Salvador, egg laying occurs from December to March (Dickey and van Rossem 1938; West 1988). In Panama, a similar breeding season has been recorded (Wetmore 1965). Similar dates were recorded by Willis and Eisenmann (1979) but they also recorded eggs in a nest between 28 October and 6 November 1976. In Colombia, two eggs were collected from a nest at Tabanga in the Santa Marta region on 12 July (Todd and Carriker 1922). In Trinidad, Williams (1922) reported eggs in February 1918, and young birds on 22 May 1918; and 24 February 1919. In Guyana, Young (1929) recorded an egg and a half-grown nestlings in October 1924. In Brazil, Oniki and Willis (1983) describe two eggs which hatched on about 29 May 1968 in Belem, and two downy young on 13 August 1972. In Argentina, nesting records exist from Reserva El Bagual, Formosa Province, from 26 July to 15 December (Di Giacomo 2005).

Black vulture clutches usually comprise two pale greenish-white, dark brown blotched eggs (Fig. 3.1d), this number being recorded in Panama (Willis and Eisenmann 1979), Guyana (Young 1929) and Argentina (in a few cases one or three eggs in this country) (Di Giacomo 2005). The color may vary; in the United States, eggs have been recorded as having a very pale bluish tinge (Wolfe 1938). In South America however, eggs from several South American countries, including Chile, Trinidad, Brazil and Paraguay did not have the bluish tinge seen in North America (Wolfe 1938). In Argentina, eggs are described as variably creamy white, whitish, pale greenish, pale bluish and either unmarked or heavily marked with reddish, brownish or blackish markings. Eggs in the clutch have different markings (Di Giacomo 2005). In Ecuador, the incubation period varies, e.g., in Argentina, it was 39-41 days (Di Giacomo 2005); in Tennessee and Ecuador it was 35 days (Crook 1935; Marchant 1960); and in Brazil it was 32 to 39 days (Sick 1993). Nesting periods also varied; for example in Brazil it would be 70 days (Sick 1993), while in Argentina it would be 74-81 days (Di Giacomo 2005). Fergus (2003) notes that young remain in the nest for two months, and can fly after 75 to 80 days.

Population status. The distribution of the Black vulture is shown in Fig. 3.1e. The Black vulture is protected in the United States under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). In Canada it is protected by the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds in Canada (1917) and the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994. In Mexico, it is protected by the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Game Mammals (1937).

The Black vulture has been described as the most common bird of prey in the western hemisphere (Brown and Amadon 1968). Although in the past it was thought to be declining (Rabenold and Decker 1990; Buckley 1999), it 'thrives today' (Blackwell et al. 2006: 1976). Blackwell et al. (2006) note that despite opinions supporting the decline of vultures in the southeastern United States (see Stewart 1984; Rabenold and Decker 1990; Buckley 1999), possibly due to nest site losses and eggshell thinning (Jackson 1983; Kiff et al. 1983; Rabenold and Decker 1990), evidence shows that adult survival (in addition to the secondary factor of fertility) is contributing to stronger populations. This is possibly because among other factors, birds may be breeding earlier in life than assumed (Blackwell et al. 2006).

The population is estimated to be 20 million birds (Rich et al. 2004). Furthermore, its population is increasing. Seamans (2004) and Sauer et al. (2001) write that Black vulture populations have increased at annual rates of 2.3% in eastern North America, 1966-2000. Trend records from the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) and the Christmas Bird Count show population increases in the United States (Sauer et al. 1996, 2005; Avery 2004) and range expanses northeastward into southern New England and northwards into Ohio (Greider and Wagner 1960; Buckley 1999; Blackwell et al. 2006).

Unlike the other species mentioned so far in this book, which are mostly endangered or declining and require supports in their relationships with people; the interactions between the Black vulture and people is largely concerned with increasing conflicts, centred on collisions with aircraft (DeVault et al. 2005; Blackwell and Wright 2006), attacks on livestock (Lowney 1999; Avery and Cummings 2004) and damage to property (Lowney 1999). The United States Department of Agriculture (2003) notes that 'More damage is attributed to black vultures, although turkey vultures have been implicated in some situations.' Danger to livestock includes 'plucking the eyes and eating the tongues of newborn, down, or sick livestock, disemboweling young livestock, killing and feeding on domestic fowl, and general flesh wounds from bites.' Both vultures have been implicated in roosting problems which include fecal matter droppings, water pollution and electricity outages.

The solutions to these problems are divided into the non-lethal methods (Avery et al. 2002; Seamans 2004) and those that require the killing of vultures; the latter is illegal due to the vulture's protected status (e.g., Holt 1998). Nevertheless, non-lethal methods, which may involve displacement of the offending birds may not be successful, as the vulture is very mobile and may return or relocate, causing problems elsewhere (Blackwell et al. 2006). Population reduction methods are possible but problematic, as more information on the birds' demographics and life history may be needed, such as age-specific survival, age-at-first-breeding, fecundity, and age distribution (Parker et al. 1995; Buckley 1999; Humphrey et al. 2004; Blackwell et al. 2006).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 238;