King Vulture (Sarcoramphus papa, Linnaeus 1758)

Physical appearance. The King vulture is the only member of the Genus Sarcoramphus (Dumeril 1805). After the condors, the King vulture is the largest New World vulture. From bill to tail, it averages 67-81 centimeters (27-32 in), with a wingspan of 1.2-2 meters (4-6.6 ft) and a weight of 2.7-4.5 kg (6-10 lb) (Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A 2001). The plumage is mostly white, usually with a perceptible rose yellow tint, while the wing coverts, flight feathers and tail are contrasting dark grey to black. The wings are broad and the tail is also broad and square (Howell and Webb 1995).

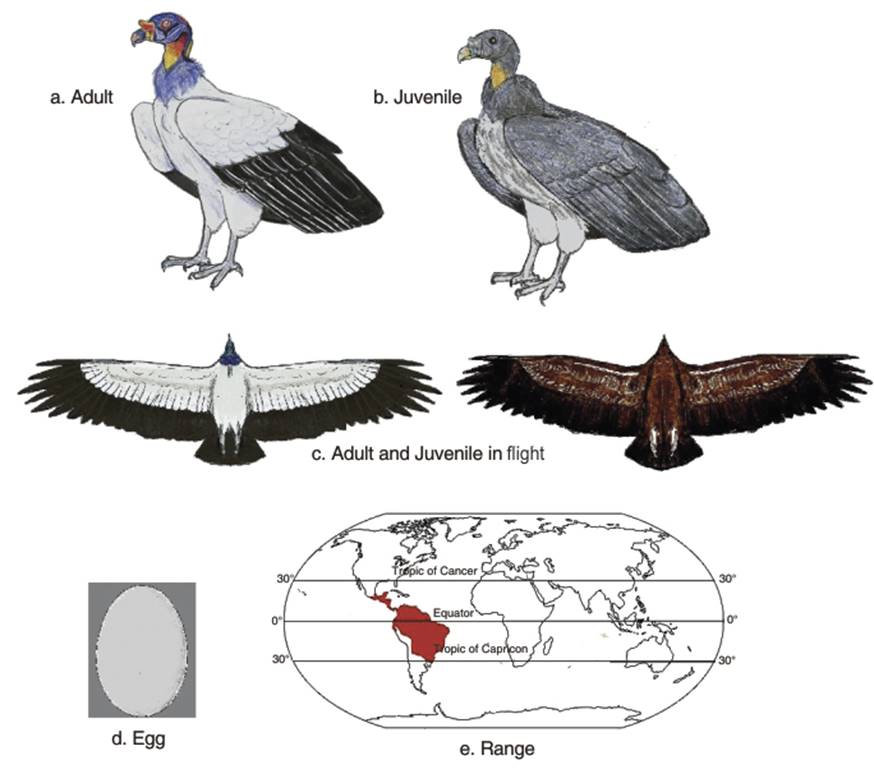

The head is complicated, the most multi-colored among the New World vultures. The bald skin, includes yellow, orange, blue, purple, and red, with a fleshy, yellow caruncle on its beak (Fig. 3.5 a,b,c). There is also a feathery, grey-white ruff (Gurney 1864; Terres 1980; Houston 1994). This species has the largest skull and strongest bill of the New World vultures (Fisher 1944; Likoff 2007).

Fig. 3.5. King Vulture

In the juvenile, the crest or caruncle is absent until the fourth year (Gurney 1864). The juvenile also has a downy, gray neck and a dark bill and eyes, slate gray plumage, that gradually changes to the adult colors by the fifth or sixth year (Howell and Webb 1995; Eitniea 1996). The juveniles resemble Turkey vultures, but may be distinguished by their flat-winged flight (the latter carries its wings in a broad "V" (Hilty 1986).

Classification. The classification of the King vulture has been changed over the years. It was first classified in the Genus Vultur (where the Andean Condor is now) as Vultur papa by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae, using a specimen from Suriname. In 1805 the French zoologist Andre Marie Constant Dumeril, changed its classification to the Genus Sarcoramphus. In 1841, Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger placed it in the Genus Gyparchus, but this was not universally recognized (Peterson 2007). Despite the removal of the King vulture from Vultur, the Andean Condor (Vulture gryphus Linnaeus, 1758) is recognized as its closest living relative (Amadon 1977). Some past authors placed the Andean Condor and the King vulture in a separate subfamily from the rest of the New World vultures, but this classification was not universally upheld (Coues 1903: 721). Although Amadon (1977) described this classification as invalid, the basis was to group the New World vultures into two groups.

Baird et al. (1874: 336-337) defined the two groups as follows:

a) 'Crop naked. Male with a fleshy crest or lobe attached to the top of the cere. Bill very robust and strong, its outlines very convex; cere much shorter than the head (Vultur, Sarcoramphus).'

b) 'Crop feathered. Male without a fleshy crest or other appendages on the head. Bill less robust, variable as to strength, its outlines only moderately convex, cere nearly equal to the head in length (Coragyps, Cathartes, Gymnogyps).'

This classification was also followed by Sharpe (1874: 20-29). Friedmann (950: 9-10) classified them according to cervical vertebrae: Vultur and Sarcoramphus 17, Gymnogyps 15, Cathartes 13, Coragyps 14. Amadon (1977: 414) however argued that the five genera of Cathartidae are more accurate, 'at least until further studies have been made' and he arranged the genera as: Coragyps, Cathartes, Gymnogyps, Vultur, Sarcoramphus, 'thereby placing Gymnogyps between Cathartes and Vultur.'

Fisher (1944) also used the skulls of the New World vultures to determine that the King vulture had the strongest bill, with the most raptor-like hook to the upper mandible and the widest gape. This feature was noticed in its feeding, as it has a greater ability to tear through the skin of carcasses than the smaller Cathartid vultures (Schlee 2005). In this respect, the King vulture performs a role similar to the Old World tearers (Lappet-faced, White-headed and Red-headed vultures), while the smaller Cathartids have the role of the pickers (the Hooded and Egyptian vultures).

Foraging. The King vulture, similar to the Greater Yellow-headed vulture, is primarily a denizen of the tropical lowland forests from southern Mexico to northern Argentina, mostly below 1500 m (5000 ft). It is also found in the nearby savannas and grasslands, and swamps or marshes (Wood 1862; Brown 1976; Houston 1994; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). The King vulture is described as being outnumbered by the Greater Yellow-headed vulture in the Amazon rainforest, while it is also outnumbered by the Lesser Yellowheaded, Turkey and American Black vultures in more open grassland and savanna (Houston 1988, 1994; Graves 1992; Restall et al. 2006). It is generally a solitary forager, but may also bathe and feed in groups where the food is abundant. Despite its status as a carrion eater, it is also recorded taking injured small animals, newborn calves and small animals such as lizards (Baker et al. 1996; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

Lemon (1991: 700) admits that 'Little is known about the foraging behavior or physiology of King Vultures', but notes that it is a forest specialist (see also Schlee 1995). There is debate about the strength of the sense of smell of the King vulture. Currently, the debate continues; there are records that it follows the Cathartes vultures with strong olfactory senses, to carcasses (Houston 1984, 1994; Beason 2003). However, Lemon (1991) provided evidence that King vultures located carrion in dense forest without the presence Cathartes vultures. At carcasses, the King vulture displaces the smaller, weaker billed Cathartes and Black vultures, but defers to the Andean Condor (Wallace and Temple 1987; Lemon 1991; Houston 1994). It uses its rasp-like tongue to remove flesh from bones and eats mainly the skin and harder tissue. It also occasionally eats fruit such as that of the Moriche Palm (Mauritia flexuosa L.f.) (Schlee 2005).

Breeding. The King vulture is non-migratory and is usually a solitary rooster and breeder. Unlike the Turkey, Lesser Yellow-headed and American Black vulture, it generally lives alone or in small family groups. Similar to these other vultures, no nest is built, but eggs are laid on bare surfaces in caves, crevices in cliffs, tree stumps or in the base of spiny palms. Schlee (1995: 269) notes that 'Several nest records indicate that king vultures are ground- nesters.'

Examples include: two nests in Panama, one in a tree stump cavity 30 cm high, in dense moist forest near a river; and another near the base of a spiny palm on the forest floor, composed of leaves and dirt scraped together (Smith 1970). A nest near the Rio Candelaria in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico was in a cavity 6-7 m high in a Pucte tree (Gomez de Silva 2004). A nest in El Salvador was in a cavity in a buttressed volador (Terminalia oblonga) tree and another was on a decayed tree stump (Thurber et al. 1987; West 1988). In Brazil a nest at Matozinhos, Minas Gerais was located in a crevice 70 m high in a limestone wall (Carvalho Filho et al. 2004) although others were in trees (Sick 1993).

The clutch size is usually one creamy or dirty white egg (Wolfe 1951; Smith 1970; West 1988; Sick 1993) (Fig. 3.5d). The incubation period is usually 50-58 days (Heck 1963; Cuneo 1968; Sick 1993). Fledging is about 130 days (Carvalho Filho et al. 2004). It is mooted that the King vulture breeds once every two years (Carvalho Filho et al. 2004).

Population status. The distribution of the King vulture is shown in Fig. 3.5e. It has a wide range, occurring in southern Mexico and northern Argentina, but although not endangered its population is believed to be declining due to habitat (forest) destruction (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; BirdLife Inernational 2014). Schlee (1995: 271) noted that 'Unlike the smaller cathartids, the king vulture is reported as not adapting well to human presence and as being more frequently seen in heavily forested areas that do not have permanent human occupation (Clinton-Eitniear 1986; Whitacre et al. 1991; Berlanga and Wood 1992). Schlee (1995: 272) notes that deforestation can 'severely strain and possibly eliminate' king vultures. More recent assessments of the population also hint at gradual decline (BirdLife International 2014).

In the older literature it was already described as either declining or moderately stable. In Mexico, it was recorded as extinct in former habitat in Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz (Winker 1987). It was also recorded as endangered in El Salvador (Komar and Dominguez 2001) and in Ecuador where it declined greatly over the 20th century, due to deforestation and agricultural development (Ridgely and Greenfield 2001). It was described as near threatened in Paraguay (del Castillo and Clay 2005) and rare in Brazil, due to trophy hunting and medicinal use (Sick 1993). On the other hand, in Panama there was less evidence of a decline (Ridgely and Gwynne 1989).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 207;