Cape Vulture (Gyps coprotheres) (Forster 1798)

Physical appearance. The Cape Griffon vulture or Cape vulture is a large to very large vulture, larger than the Ruppell's or White-backed vultures. It occurs only in southern Africa, i.e., South Africa, Lesotho, Botswana, and is labelled as 'Critically Endangered' in Namibia (Simmons and Brown 2007). The length from bill to tail end is about 96-115 cm (38-45 in), the wingspan about 2.26-2.6 m (7.4-8.5 ft) and the weight 7-11 kg (15-24 lb) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

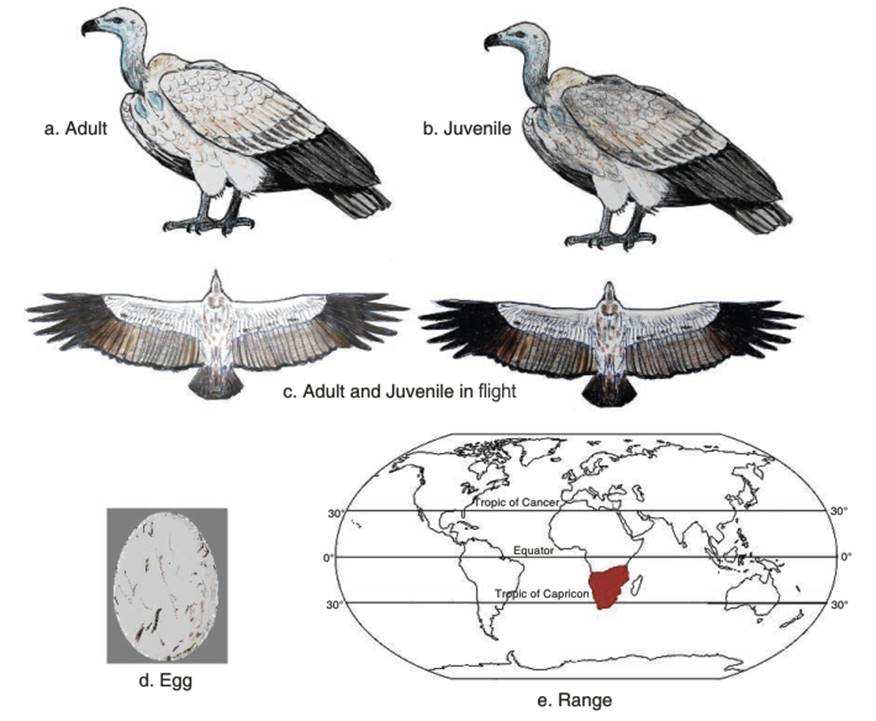

The coloration for an adult is creamy-buff, which contrasts with dark flight and tail feathers. The neck ruff is pale buff to dirty white. Light silvery feathers and a black alula are visible in the underwing during flight. A black bill and its slightly larger size distinguish this species from the Ruppell's Griffon vulture. The juveniles have a darker, streaked plumage and a reddish neck (Fig. 1.6a,b,c).

Fig. 1.6. Cape Vulture

Classification. Johnson et al. (2006: 72) in a molecular study of the Gyps genus, noted a strong relation between G. coprotheres, G. i. indicus and G. i. tenuirostris in a clade, with these related to another clade of G. f. fulvus and G. rueppellii. Older publications held that the Cape vulture formed a superspecies with the Eurasian Griffon and Ruppell's vulture. In this classification, the Cape vulture would be a subspecies of Gyps fulvus (Stresemann and Amadon 1979; Amadon and Bull 1988). A close relation between G. coprotheres and G. fulvus was also supported by Wink (1995). This was based on the divergence in nucleotide sequences in the cytochrome b gene. Wink suggested that the two species diverged from a common ancestor about half a million years ago.

Foraging. Cape vultures in Namibia were described as denizens of open habitat such as grassland and open woodland savanna, with the majority (79%) of prey animals being wild ungulates (Schultz 2007). In that study, Greater Kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros Pallas 1766) were the most common prey item (54.2% of all carcasses) followed by cattle, eland and horses. The Cape vulture is a heavy bird with a high wing loading (112 N/m). It practices fast crosscountry soaring (Pennycuick 1972). In this it contrasts with the commoner, smaller White-backed vulture in Namibia (a lighter bird with a wing loading of 76 N/m) (Pennycuick 1972; Bridgeford 2004). Possibly the White-backed vulture may have evolved in the denser wooded savanna, and hence is more adapted to bush encroachment than the Cape vulture, which may favor a more open grassland (Brown 1985; Schultz 2007). The White-backed vulture frequents alpine grassland, followed by moist woodland, sour grasslands, arid woodland, and mixed and sweet grasslands (Mundy et al. 2007).

The Cape vulture is the only vulture in southern Africa south of 28° and thus has little foraging competition (Mundy et al. 2007). North of this area it is in competition with four other species: the common White-backed vulture, the Hooded vulture, the Lappet-faced vulture and the Whiteheaded vulture.

Breeding. The Cape vulture is a colonial cliff-nester (Bamford et al. 2007; Schultz 2007). Some individuals nest in trees (Bamford et al. 2007). Breeding usually starts in April to June, with the laying of one egg (Fig. 1.6d), with fledging between the end of October and mid-January. Juveniles normally remain in the vicinity of the colony until the following breeding season, followed by dispersal to start their own breeding some six years later (Pickford 1989; Mundy et al. 1992; Piper 1994; Hockey et al. 2005; Boshoff and Anderson 2005).

Population status. The distribution of the Cape vulture is shown in Fig. 1.6e. This species has been declining across its range (Monadjem et al. 2004; Shultz 2007). For example, in Namibia its range declined precipitously after the Second World War. All its known breeding colonies and roosts were abandoned, except for a handful of individuals by the 1990s (Mundy and Ledger 1977; Collar et al. 1994; Simmons and Bridgeford 1997; Simmons 2002). The incidence of the rinderpest disease was a factor for this decline (1886-1903) which killed many herbivorous animals, including domestic cattle. Other factors were the Anglo-Boer War, the destruction of game herds, the replacement of wild ungulate herds with domestic stock, the conversion of grazing land to cultivation and poisoning (Boshoff and Vernon 1980). Recent threats include electrocution and collision with power lines, persecution, killings for traditional medicine, drowning in farm reservoirs and human disturbances (Anderson 2000; Monadjem et al. 2004).

Bush encroachment after 1950 is a factor for the decline in the range of the Cape vulture (Schultz 2007). This involves the conversion of grassland and woodland savannas to dense acacia-dominated vegetation with minimal grass cover (Barnard 1998; Muntifering et al. 2006). This may result from changes in the incidence of bush fires and increased grazing pressure on grass (Ward 2005). There is no clear evidence that bush encroachment negatively affects vultures (Smit 2004). However, Schultz (2007) argues that it may reduce the visibility of carcasses for foraging vultures in dense bush (Houston 1974; Mundy et al. 1992). In some other studies, however, vultures have been recorded as finding non-visible food by following other avian scavengers such as the Bateleur eagle, Milvus kites, corvids and jackals (Mundy et al. 1992; Camina 2004). Bush encroachment may also indirectly reduce the livestock stocking rates and affect food sources (Bester 1996; Dean 2004; Smit 2004) which in turn may affect scavenger bird populations (Schultz 2007). Satellite image-based studies have shown that vultures prefer commercial farmland to communal areas or the protected Etosha National Park (Mendelsohn et al. 2005).

Vulture numbers in Botswana peak between protected and grazing land, as the birds may breed and roost inside conservation areas and feed on livestock in non-protected areas (Herremans and Herremans-Tonnoeyr 2000). This strategy is also observed among Griffon vultures Gyps fulvus in Israel (Bahat 1995; Schultz 2007).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 218;