Griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus, Hablizl 1783)

Physical appearance. The Griffon vulture, also called the Eurasian Griffon vulture or Common Griffon vulture is a large to very large vulture, and very closely related to the Cape Griffon vulture when molecular phylogeny of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cyt) gene is used (Wink 1995). The Griffon vulture is one of only a few vulture species resident in Africa, Asia and Europe; the others are the Bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus, the Cinereous vulture Aegypius monachus and the Egyptian vulture Neophron percnopterus (Houston 1983; Mundy et al. 1992; Clark 2001).

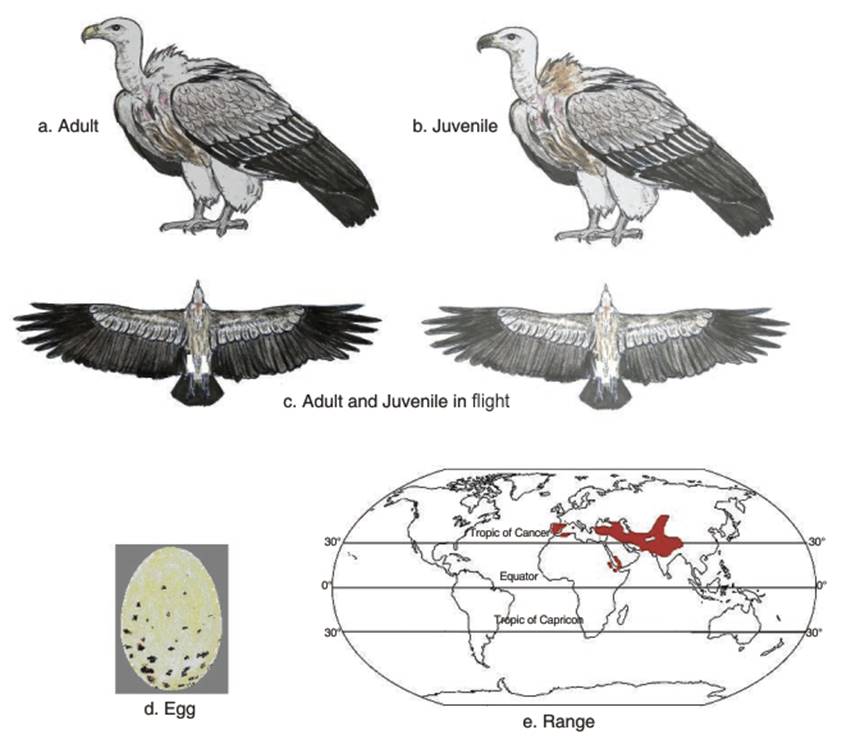

The body length and tail is 93-122 cm (37-48 in), while the wingspan ranges from 2.3 to 2.8 m (7.5-9.2 ft). Males usually weigh 6.2 to 10.5 kg (14 to 23 lbs) and females about 6.5 to 11.3 kg (14 to 25 lbs). This species has a yellow bill and white neck ruff. The buff body and wing coverts contrast with the dark flight feathers (Ali 1996; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001) (Fig. 1.7a,b,c).

Fig. 1.7. Griffon vulture

Classification. There are currently two recognized subspecies: Gyps fulvus fulvus and Gyps fulvus fulvescens. The former is found in Spain, Southern France and Morocco, eastwards to the eastern Mediterranean. The latter is found in northern India, north into Kyrgyzstan, Russia and the western Himalayas. Johnson et al. (2006: 66) note that their study represents the 'first attempt to ascertain Gyps systematics based on samples of all recognized species using molecular techniques'. The results show that the 'taxonomic status of the two subspecies of the Eurasian vulture (G. f. fulvus and G. f. fulvescens), as well as their characteristics and geographic distribution are unclear', possibly as G. f. fulvescens has not been included in a study of molecular phylogenetics, it may even be a different species. The evidence for this assertion is that the results for the two subspecies G. f. fulvus and G. f. fulvescens were 'phylogenetically distinct'; they were 'not placed as sister taxa', and importantly the samples of the G. f. fulvescens clustered with the Himalayan Giffon vulture (G. himalayensis) rather than with G. f. fulvus. Therefore the two subspecies, fulvus and fulvescens, were found to be phylogenetically distinct, not sister taxa, and further study might elevate both to different species.

Foraging. Garcia-Ripolles et al. (2011: 127) state that 'little is known about the spatial ecology and ranging behavior of vultures in Europe', therefore they use GPS satellite telemetry to assess home-ranges of Eurasian Griffon vultures in Spain. The results showed that the birds ranged mainly in areas with traditional stock-raising practices, pasturing and to a lesser extent vulture restaurants. Griffon vultures may use temporary communal roosts where there is high food availability (Donazar 1993; Xirouchakis 2007; Olea and Mateo-Tomas 2013).

The Griffon vulture is almost exclusively a carrion-eater, with few records of killing injured and weak sheep or cattle (Camina et al. 1995; Camina 2004a). The diet mainly comprises livestock species (sheep, goat, cattle and horses) (Fernandez 1975; Camina 1996). Wild ungulate carcasses, such as those of Rupicapra rupicapra, Cervus elaphus, and Capreolus capreolus are eaten in mountain areas such as the Pyrenees and the Alps.

Many records show a dependence on domestic livestock (Donazar 1993; Tucker and Heath 1994). For example, Camina in Slotta-Bachmayr et al. (2006) writes that in Spain, they are strongly dependent upon domestic pigs, cattle and sheep. A similar situation obtains in Portugal, where there is a tradition of putting carcasses out for vultures. Fernandez y Fernandez- Arroyo (2012) point out that the recent compulsory removal of animal carcasses in Spain has reduced vulture numbers (Camina 2004b; Tella 2006; Camina 2007; Camina and Lopez 2009; Fernandez 2007a, 2007b, 2009; Melero 2007; Perez de Ana 2007; FAB 2008; Gonzalez and Moreno-Opo 2008; Suarez Aranguena 2008).

The carcass removal programme against the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) in the Ebro of Aragon, Spain, decreased the food availability for vultures from about 3 carcasses per farm a day in 2004 to 0-0.5 carcasses in 2005 (Camina and Montelio 2006). Also, after the removal program, the proportion of adult birds increased relative to immature birds. The authors conclude that the removal program significantly affected the Griffon populations and hence requires more study. Zuberogoitia et al. (2010: 53) point out that the 'systematic removal of livestock from the mountains and the closing of vulture feeding stations in neighboring provinces have caused the local population to decline, with a simultaneous decrease in breeding parameters. Moreover, mortality due to starvation has become increasingly common in recently fledged birds of some vulture colonies' (see also Zuberogoitia et al. 2009).

The reduction in vulture numbers has also been seen in the French Pyrenees (LPO 2008; Razin et al. 2008). In Armenia, the situation is similar (Ghasabian and Aghababian 2005; Slotta-Bachmayr et al. 2005), but there is greater access to wild animal carcasses, including wild ibex and bears (Adamian and Klem 1999).

Griffon vultures in Spain and southern France may kill livestock, to the anger of local farmers (Margalida et al. 2011). Changes in European sanitary and conservation policies in 2002, to control the spread of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (commonly termed mad cow disease), and regulations for animal husbandry, which required that all carcasses be removed from farms are considered factors for these killings. Griffon vulture populations in Western Europe have also increased in the last decade, while those in the Eastern Mediterranean have declined (Parra and Telleria 2004; Slotta- Bachmayr et al. 2005). Margalida et al. (2011) write that there were 1,165 reported cases of vultures killing livestock in 2006 to 2010 in northern Spain. The compensation cost was nearly $350,000. In retaliation, stakeholders poisoned 243 vultures during this period.

Breeding. The Griffon vulture is a cliff nester, usually nesting on cliffs below 1,500 m in elevation and rarely in trees (sometimes in those of Cinereous vultures) (Traverso 2001; Xirouchakis and Mylonas 2005). It is also a colonial breeder, with colonies numbering up to 100 pairs (Del Moral and Marti 2001). Gavashelishvili and McGrady (2006), using the results of a study in the Caucasus, found that the probability of a cliff ledge being occupied by Griffon vulture nests was positively correlated with the percentage of open areas and the annual biomass of dead livestock, and was negatively correlated with annual rainfall. The breeding season extends from December/January until July, and the brood consists only of one chick (Donazar 1993). The egg is white, with light brown spots (Adamian and Klem 1999) (Fig. 1.7d).

Population status. The distribution of the Griffon vulture is shown in Fig. 1.7e. This species was once classified as threatened, but has recovered its numbers and is now classified as of least concern (BirdLife International 2007). Large populations are found in the Iberian Peninsula (Del Moral and Marti 2001). Crete 'supports the largest insular Griffon vulture population in the world' (Xirouchakis and Mylonas 2005:229). The very large range of the Griffon vulture is possibly a factor for its survival, as it encounters different circumstances in each of the regions that it inhabits (Parra and Telleria 2004). For example, in Italy in 2005 the total population stood at 320-390, with supports such as supplementary feeding, and problems such as poisoned baits, new power-lines and wind-power generation projects (Genero 2006). In Croatia, they are rare and possibly declining, with less than 200 birds in 2005. Problems include illegal poisoning, the end of traditional sheep farming in breeding areas, and disturbances from tourism or recreation near nest sites (Pavokovic and Susic 2006). In France, intensive work on conservation and re-introduction has resulted in increased populations (Tarrasse et al. 1994; Terrasse 2004; Terrasse 2006). In Cyprus, the Griffon vulture is one of the most threatened birds (Iezekiel and Nicolaou 2006). In Sicily, it was common throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but it became extinct in 1969, due to poisoning (Priolo 1967). It has since been reintroduced, and a small population of about nine are breeding (Vittorio 2006).

In the countries of the former Soviet Union, Katzner et al. (2004a: 235) note that although there is 'no sign of severe decline in vulture populations', there are few or no records of Griffon breeding and population status. Russia and Uzbekistan are recorded as having the largest number of this species, and there are no records of breeding in Belarus, or in the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania). The Ukraine has a small population in the Carpathians, and it appears the breeding population in Moldova. Populations in the Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Russia) are listed as declining. The most important factor for these declines is the 'massive declines in the number of livestock herded throughout this region' (Katzner et al. 2004a: 239).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 162;