Californian Condor (Gymnogyps californianus, Shaw 1797)

Physical appearance. The California condor is the only living member of the Genus Gymnogyps (Lesson 1842). Other members or possible members of this genus are extinct; for example G. californianus amplus, slightly larger than the modern condor, from the Late Pleistocene. The California condor is one of the largest flying birds in North America, nearly the length and weight of the Trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator, Richardson 1832), Mute Swan (Cygnus olor, Gmelin 1789), American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos, Gmelin 1789) and Whooping crane (Grus americana, Linnaeus 1758).

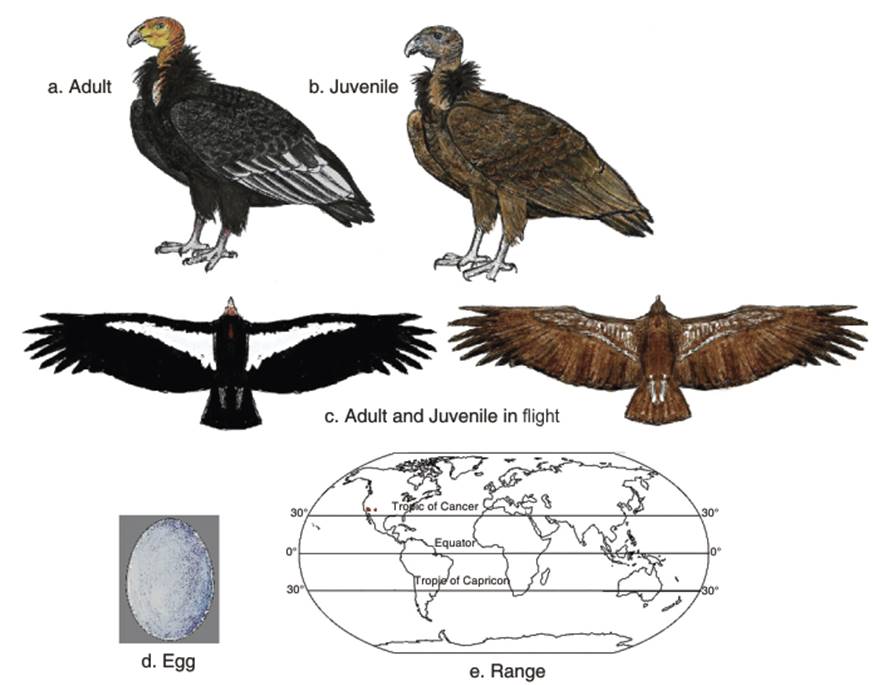

The California condor is usually slightly smaller than the Andean condor, with slightly shorter wings and a slightly longer body. The length is usually from 109 to 140 cm (43 to 55 in) and the wingspan from 2.49 to 3 m (8.2 to 9.8 ft), despite unverified reports up to 3.4 m (11 ft) (Wood 1983). The weight is generally 7 to 14.1 kg (15 to 31 lb), with estimations of average weight ranging from 8 to 9 kg (18 to 20 lb) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). In coloration, the plumage is black with triangular white patches on the underside of wings (Fig. 3.6 a,b,c). The bill is white and the bare skin of the head varies from yellow to reddish orange (but can flush more reddish according to emotional state). There is a ruff of black feathers around the base of the neck and the legs and feet are grey. The juvenile plumage is mottled dark brown, with mottled grey replacing the white wing patches (BirdLife International 2014).

Fig. 3.6. California Condor

Classification. The California condor was described by the English naturalist George Shaw in 1797 as Vultur californianus, in the same Genus as the Andean Condor (V. gryphus), but diferences resulted in the separation of this species from the Genus Vultur (Nielsen 2006). Amadon (1977) also suggested merging Gymnogyps with Vultur, but this idea was later abandoned (Amadon and Bull 1988).

Foraging. The California condor has a very large foraging range, up to 250 km (150 mi). The favored landcover is rocky shrubland, coniferous forest, and oak savanna in flatland and more mountainous areas. An important former foraging habitat was the littoral zone of the Pacific Coast, which is gradually being recolonized by birds released from captivity. Currently, there are two condor sanctuaries for birds released from captivity, the Sespe condor Sanctuary in the Los Padres National Forest and the Sisquoc Condor Sanctuary in the San Rafael Wilderness.

Before North America was colonized, the main sources were small and large wild animals, from ground squirrels to large ungulates and marine mammals. Later, cattle and sheep carcasses on ranches predominated. Condors tend to feed mostly on muscle and viscera when at larger carcasses. Unlike the Cathartes vultures, the California condor does not have a sense of smell. Therefore, condors follow these species to food sources (Nielsen 2006). Condors are usually dominant over Turkey and Black vultures and ravens at carcasses, but are usually driven away by Golden eagles (Koford 1953).

Breeding. Cliff caves or crevices, rocky outcrops or large trees are used as nest sites (United States Fish and Wildlife Service 1996). The egg-laying period is January to April. One bluish-white egg is laid every other year (Fig. 3.6d). In most cases, when an egg or chick is lost, another egg is laid as a replacement. Eggs are laid from January to April (Snyder and Snyder 2000). The incubation period is about 53 to 60 days and the fledging period is about five to six months.

Population status. The distribution of the California condor is shown in Fig. 3.6e. Condors ranged widely across the North American continent at the commencement of human habitation until a few hundred years ago (Miller 1931, 1960; Wetmore 1931, 1932, 1938; Majors 1975). There was a sharp decline in the population of the California Condor during the 20th century; the main factors were poaching, lead poisoning, and habitat destruction (Graham 2006; Cade 2007; Parish 2007). Other factors were collisions with electric power lines (Kiff et al. 1979), DDT poisoning (Church et al. 2006), shooting (Finkelstein et al. 2012) and poor food (Rideout et al. 2012). Thacker et al. (2006) note that lead bullets pose a problem for condors, due to their strong digestive juices, which is less of a problem for smaller scavengers such as ravens and Turkey vultures.

In 1987, all the 22 remaining wild condors were captured, and placed for protection and breeding in the Los Angeles Zoo and the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. In 1991, Condors were reintroduced into the wild. By May 2012, the total population was recorded as 405, of which 226 were in the wild and 179 were captive (Hunt et al. 2007; California Condor Recovery Program 2012; BirdLife International 2014).

Austin et al. (2012: 13) note that 'Lead poisoning continues to be the number one diagnosed cause of mortality' for the condors reintroduced into the wild. Over 90% of condors released in Arizona had lead in their system (BirdLife International 2014) and some birds have died (Austin et al. 2012) while others have been treated for different ailments (Parish et al. 2007; Walters et al. 2010).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 217;