Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotus (Forster 1791)

Physical appearance. The Lappet-faced vulture is a very large vulture, rivalling the Cinereous vulture, Cape vulture and Eurasian griffon in size, and almost the same size as the New World condors. It is the most aggressive and powerful African vulture, and dominates other vultures at a carcass. It measures between 78 and 115 cm (31-45 in) in the length of body and tail, with a 2.5-2.9 m (8.2-9.5 ft) wingspan, and a weight of 4.4. to 13.6 kg (9.7-30 lb) (Ferguson- Lees and Christie 2001; Hockey et al. 2005; BirdLife International 2014). It has one of the largest bills (up to 10 cm (3.9 in) long and 5 cm (2.0 in) deep) of all accipitrids, only equaled by that of the Cinereous vulture (Hardy 1947; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

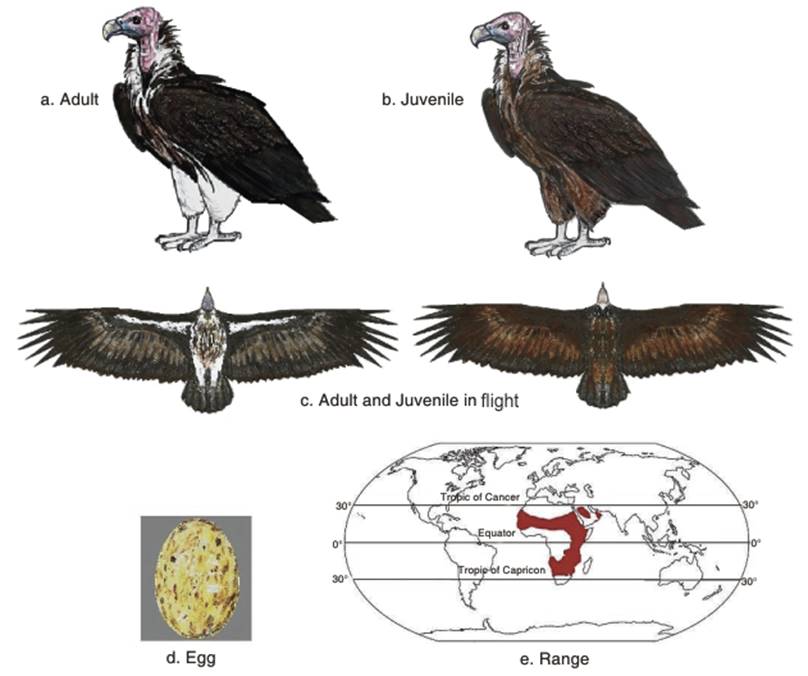

The plumage is largely blackish on the back and on the backs of the wings. In African birds, the black back feathers have brown linings, while the Arabian birds are brown, not black above. The underside is white to pale brown, and the thigh feathers are white. The head varies in color; usually pink on the rear of the head and greyish in front in birds from Arabia, pink in northern African birds and reddish in southern African birds (Fig. 2.6 a,b,c). It thus varies greatly from the Gyps vultures, which are much paler with less white lining in the wings. It also varies from the more similar Hooded vulture by its much larger size, and from the Cinereous vulture (both species overlap in range in the Arabian peninisula) by the latter's all dark plumage (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001).

Fig. 2.6. Lappet-faced Vulture

Classification. As described for the other species, the Lappet-faced vulture is classified using molecular sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene, as belonging to the clade of Old World vultures, which contains the genera Aegypius, Gyps, Sarcogyps, Torgos, and Trigonoceps (Wink 1995). The findings of some studies supported the merging of four monotypic genera of large Old World vultures into one single genus named Aegypius (Stresemann and Amadon 1979; Amadon and Bull 1988; Wink 1995). It has been suggested that this species is a recent offshoot of the Cinereous vulture Aegypius monachus (Wink and Sauer-Gurth 2000, 2004).

Further analyses using the sequences of the cytochrome b gene, supported the existence of subspecies, as there was evidence of a small genetic distance between the nominate subspecies Torgos tracheliotus tracheliotus and another subspecies Torgos tracheliotus negevensis (Wink 1995). The latter had already been described as a separate subspecies (Bruun et al. 1981). Although earlier studies hypothesized that Torgos tracheliotus negevensis was a cross between the Lappet-faced vulture and the Cinereous vulture (Aegypius monachus), the study by Wink (1995), using the maternal cytochrome b gene showed it could not be a link between a female A. monachus and a male Torgos due to the similarity between T. t. tracheliotus and T. t. negevensis, and the greater differences between T. t. negevensis and A. monachus. The other possibility, a mating between a male A. monachus and a female T. t. tracheliotus was considered possible but remote. A divergence between T. t. tracheliotus and T. t. negevensis was hypothesized at about 350,000 years BP, this estimation being based on the so-called 2% per million years rule (Shields and Wilson 1987; Wink 1995).

As a result of these studies, there are three recognized subspecies of the Lappet-faced vulture (Bruun et al. 1982; Shobrak 1996). T. t. tracheliotus from south and east Africa, differs in having white-feathered thighs, a scarlet bald head and larger skin folds or lappets on the head. Mundy et al. (1992) note that East African adult birds have a black bill, while those of southern Africa have yellow bills. T. t. negevensis is found mainly in Israel and the Arabian Peninsula (Mendelssohn and Marder 1989). This subspecies has brown rather than black plumage, greyer skin on the face and a pink colored rear of the head. It has a thicker down on the head, and either an absence of lappets or smaller lappets. The thighs are covered with dark brown rather than white feathers, and the bill is blackish (Brunn et al. 1981).

T. t. nubicus, a hybrid of the recognized subspecies may constitute a third subspecies in Egypt and Sudan (Bruun 1981; Mundy et al. 1992). It is identified by very small lappets, a pink head and brown feathers on the thighs. Not all authors recognize this third subspecies (Cramp and Simmons 1980; Brown et al. 1982; Weigeldt and Schulz 1992). In the past, before DNA studies, the classification of subspecies considered the 'size of the lappets, the coloration of the head, color of the thighs, and the degree of development of a white bar on the underwing' (Weigeldt and Schulz 1992: 24; see also Bruun 1981; Bruun et al. 1981; Leshem 1984). Some studies emphasized the lack of geographical separation between the Negev and Arabian populations (Brown et al. 1982; Jennings and Fryer 1984) and variabiity of individual colors from both populations (e.g., variation of thigh colors between brown and white, as reported by different authors, e.g., Bruun et al. 1981; Mendelssohn and Leshenm 1983; Leshem 1984; Shirihai 1987; Mendelssohn and Marder 1989).

Weigeldt and Schulz (1992: 24) argue that 'it appears that initial description and classification of T. t. negevensis was based on only a very few birds, and the variability of the characters employed has not been considered in sufficient detail.' Therefore, 'it has to be concluded that the two populations are not morphologically distinct' (ibid.). These authors also question the distinction between T. t. negevensis and T. t. nubicus and T. t. tracheliotus, although they acknowledge the differences (using color of head, size of lappets and feather coloration) between the Arabian and African populations are greater than those between the Arabian and Negev populations.

Foraging. This species favors dry open savannas, deserts and open mountain slopes (Ferguson-lees and Christie 2001; Shimelis et al. 2005), up to elevations of 3,500 m (Shimelis 2007). It also enters denser habitats and even human habitated areas, feeding on human discards, dead livestock and road kills. In Ethiopia, it has been recorded near forest-edge vegetation and in the Bonga forest and forest in Bale Mountains National Park in 2007, and in the high altitude alpine habitats of this national park (Shimelis 2007). The Lappetfaced vulture is a wide range forager and although mainly a scavenger, it is also a predator for small reptiles, fish, birds and mammals, and even hunts young flamingos (Phoenicopterus spp. Linnaeus 1758) (Mundy 1982; Mundy et al. 1992; McCulloch 2006a, 2006b). It also feeds on dead livestock, as in Saudi Arabia (Newton and Newton 2008).

While Andersson (1872) termed this species 'sociable', Roberts (1963, in Sauer 1973) referred to it as 'less sociable' than other vultures. However, several observers agree that the Lappet-faced vulture is solitary, as foraging pairs usually outnumber groups and it usually attends carcasses in smaller numbers than the griffons (Mundy et al. 1992).

Breeding. The Lappet-faced vulture is principally a tree nester (Brown et al. 1982). Nests are often located in trees of Maerua spp. (Forssk.), about 4.5 m high (Weigeldt and Schulz 1992). The mostly solitary nests are commonly in acacia, balanites and terminalia (Boshoff et al. 1997; Shimelis et al. 2005). Bolshoff et al. (1997) gives evidence that in some cases the distribution of the Lappet-faced vulture is limited by the distribution of the acacia. The low density of the nests has been compared with other species. For example, while White-backed vultures were recorded with average nesting densities of 49.8 nests/100 km2, with areas up to 266 nests/100 km2 in Swaziland, Lappet-faced vultures had a 'high' nesting density of only 1.5 nests/100 km2 (Monadjem and Garcelon 2005; see also Mundy et al. 1992), which was higher than those for the Kruger National Park (Tarboton and Allan 1984). Comparatively high figures of 2-7 nests/100 km2 were reported from Kenya and Zimbabwe (Pennycuick 1976; Hustler and Howells 1988; Mundy et al. 1992; Monadjem and Garcelon 2005).

The nesting period is from November-July/September in the north of the range, throughout the year in East Africa, and May to January in southern Africa (see also Shimelis et al. 2005; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). It mostly lays a single egg (Fig. 2.6d). Newton and Newton (2008), studying birds in western Saudi Arabia, wrote that most eggs were laid in December, the time of the lowest mean daily air temperatures and young birds fledged after 180 days. The clutch is 1-2, incubation 54-56 days, fledging 125-135 days, and juveniles attain breeding age at about six years (Shimelis et al. 2005).

Population status. The distribution of the Lappet-faced vulture is shown in Fig. 2.6e. Although distributed across sub-Saharan Africa and Arabia, Yemen, Oman and the United Arab Emirates, the population of the Lappet-faced vulture has been described as declining, especially in the Sahel and parts of western, northern and southern Africa (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). In Syria, birds have been killed for medicine and have also died after ingesting meat from poisoned carcasses (Serra et al. 2005). It may be extinct in Israel since the 1990s (Yosef and Hatzole 1997), but T. t. negevensis is recorded as still present in Israel and the Arabian Peninsula (Mendelssohn and Marder 1989). In the Arabian Peninsula it is recorded as rare, due to human disturbance, shooting and poisoning (Aspinwall 1996). In Morocco it is extinct, due to human predation and pesticides (Sayad 2007).

In the northern Sahel, the Lappet-faced vulture was recorded as the most widespread vulture in the early 1970s, linked to the distribution of acacia trees (about 20° N) (Thiollay 2006a; Newby et al. 1987). In 2001-2004, they were very rare (Clouet and Goar 2003; Thiollay 2006a,b,c). In central West Africa, Rondeau and Thiollay (2004) and Thiollay (2006a,b,c), reported a 97% decline in numbers. Possible reasons are fewer carcasses, killing for medicine and food, contaminant poisoning, powerline electrocutions and captures for zoos (Thiollay 2006a,b,c). In parts of West and East Africa, there are similar declines (Dowsett-Lemaire 2006; Dowsett et al. 2008).

There have been few surveys of this species in southern Africa (Mundy et al. 1992). However, several authors have described population declines, with factors for this including those factors mentioned above for central West Africa (Simmons 1995; Simmons and Bridgeford 1997; van Rooyen 2000; Bridgeford and Bridgeford 2003; Borello 2004; Bridgeford 2004; Diejmann 2004; Monadjem and Garcelon 2005; Simmons and Brown 2006a; Hancock 2008b). In Mozambique, problems include large mammal declines after the colonial period and the wars following independence (Parker 2004, 2005b). It was recorded to be faring better in Zimbabwean cattle areas (Mundy 1997; Bridgeford 2004). In South Africa, it was historically common and reported to be rare towards the end of the twentieth century, but its current status is uncertain, as much of the literature is dated (Steyn 1982; Boshoff et al. 1983; Tarboton and Allan 1984; Brown 1986; Mundy et al. 1992; Anderson and Maritz 1997; Piper and Johnson 1997; Simmons and Bridgeford 1997; Verdoorn 1997a; Oatley et al. 1998; Anderson 2000, 2003; van Rooyen 2000; Bridgeford 2001, 2002a,b, 2003, 2004).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 171;