White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus (Salvadori 1865)

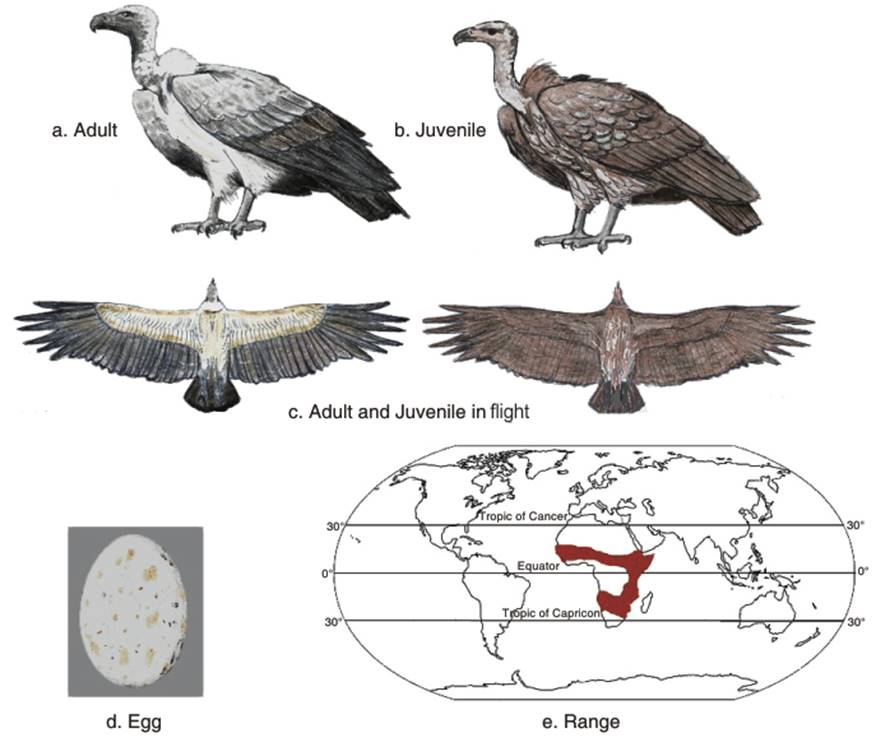

Physical appearance. The White-backed vulture is a medium-sized vulture, slightly larger than the White-rumped vulture. The body mass is 4.2 to 7.2 kg (9.3-16 lbs), it is 78 to 98 cm (31 to 39 in) long and has a 1.96 to 2.25 m (6 to 7 ft) wingspan (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). The dark tail and flight feathers, contrast with the lighter brown to cream-colored body feathers. The rump is white. The head is paler than the neck. The only other similar birds within its range are G. fulvus, and G. rueppellii, but these species are larger and have less contrast between the flight feathers and underwing-coverts (Fig. 1.2a,b,c).

Fig. 1.2. White-backed Vulture

Classification. The White-backed vulture, as described above, is closely related to the Indian White-rumped vulture, to the extent that they were (and still are in some publications) classified together, but 'grouping of bengalensis and africanus together in the Genus Pseudogyps, as historically proposed, is not upheld based on mitochondrial data' (Johnson et al. 2006: 65).

Foraging. The White-backed vulture frequents open wooded savanna, particularly areas of acacia. Phipps (2011) notes that the foraging preferences of this species are poorly understood, but its occurrence is linked to free ranging ungulates in open land. The Serengeti ecosystem in Tanzania has been cited as a good foraging ecosystem for this and other species of African vultures, based on the habitat of large wild ungulates and the carnivores that kill them to provide food for vultures (Houston 1974).

Breeding. For the nesting and egg-laying period, a study by Virani et al. (2010) in the Serengeti National Park of Tanzania found the peak period to be mid-April. Vultures may deliberately select this period for fledgling as it coincides with the peak of ungulate carcass availability (Houston 1976). Another study by Herholdt and Anderson (2006) in Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana, found that most White-backed vultures laid eggs in June. Nesting periods were observed to start in May to June in Zimbabwe, and June to July in Swaziland and KwaZulu-Natal (Monadjem 2001). Only one egg is laid (Fig. 1.2d) and incubated for about 56 days. The chick is fledged after about four months. However, Virani et al. (2012) note that despite the single annual breeding season in southern Africa (as also noted by Mundy et al. 1992), in East Africa there is a bimodal breeding season, with nesting in April/May and December/January (as also reported by Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001), and peak egg laying between March and May (Houston 1976).

Colonial nesting usually involves ten or fewer pairs, with one or occasionally two nests per tree (Mundy et al. 1992; Monadjem and Garcelon 2005). Nesting is usually in large, crowned trees in loose colonies, near rivers (Mundy et al. 1992; Bamford et al. 2009a, 2009b). Malan (2009) observed, nesting White-backed vultures predictably selected the tallest trees available. Studies by Varani et al. (2010) in the Masai Mara in Kenya, and by Monadjem and Garcelon (2005) and Bamford et al. (2009a) in Swaziland found that the White-backed vulture nests mostly in tall trees in riparian vegetation. Other studies found that nesting trees were a minimum of 11 m tall (Houston 1976; Monadjem 2003a; Herholdt and Anderson 2006). A study by Comba and Simuko (2013) found that the average height of nests in Zambia was 16.6 m. Other heights for nests were 19 m in Zimbabwe (Mundy 1982), 14 m in the Kruger National Park (Tarboton and Allan 1984), 13 m in Swaziland (Monadjem 2003) and 7 m in Kimberly (Mundy 1982). Common tree species for nests are Faidherbia albida [(Delile) A. Chev.], which grows from 6 to 30 m tall; Vachellia xanthophloea [(Benth.) PJ.H. Hurter], which grows up to 15-25 m and Senegalia nigrescens [(Oliv.) PJ.H. Hurter] which grows up to 18 m in height. Occasionally, these vultures nest on pylons in South Africa (Anderson and Hohne 2007; Malan 2009).

Population status. The distribution of the White-backed vulture is shown in Fig. 1.2e. This species has been described as the most widespread and common vulture in Africa, but in recent times it has declined (Thiollay 2006; McKean and Botha 2007; Ogada and Keesing 2010; Otieno et al. 2010). The population reduction in Western Africa is over 90% in some areas (Thiollay 2006). There have been population reductions in the Sudan (Nikolaus 2006), Kenya (Virani et al. 2011) and southern Africa (Hockey et al. 2005) Declines in Tanzania and Ethiopia are disputed (Nikolaus 2006). The conservation status has been upgraded from Least Concern to Near Threatened (BirdLife International 2007).

Habitat conversion to agro-pastoral systems, loss of wild ungulates leading to a reduced availability of carrion, hunting for trade, persecution and poisoning are factors for the declining population (Virani et al. 2011). The diclofenac compound, used to reduce pain and inflammation in livestock, acts as a poison as African and Asian vultures are vulnerable to its effects (Swan et al. 2006; Naidoo and Swan 2009; Ogada and Keesing 2010; Otieno et al. 2010; Phipps 2011). In Kenya, the toxic Carbamate-based pesticide Furadan™ has killed many vultures (Maina 2007; Mijele 2009; Otieno et al. 2010). In southern Africa, some birds are killed and eaten for perceived medicinal and psychological benefits (McKean and Botha 2007). Electrocution from powerlines is common in some areas (Bamford et al. 2009). In addition, the ungulate wildlife populations on which this species relies have declined precipitously throughout East Africa, even in protected areas (Western et al. 2009).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 217;