Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus (Scopoli 1786)

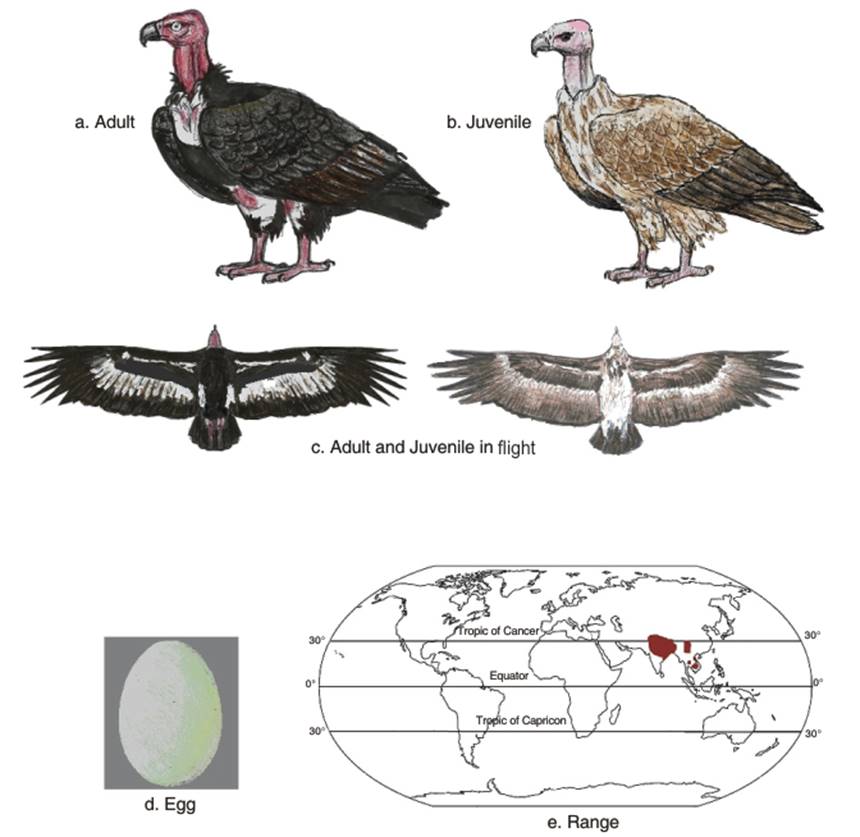

Physical appearance. The medium sized Red-headed vulture, is also named the Asian King vulture, Indian Black vulture or Pondicherry vulture (Ali 1993). It has a length of about 76 to 86 cm (30 to 34 in), a wingspan of about 1.99-2.6 m (6.5-8.5 ft) and a weight 3.5-6.3 kg (7.7-14 lb) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). In the adult, the head has deep red to orange skin, with scattered light whitish down. The iris is white in the male and dark brown in the female. The heavy bill is black with a reddish pink cere, the feet are a similar reddish to orange color to the head and the plumage is mainly dark with a grey band at the base of the flight feathers (Naoroji 2006) (Fig. 2.5 a,b,c).

Fig. 2.5. Red-headed Vulture

Classification. The Red-headed vulture was formerly named the King Vulture Torgos calvus, and is named by some as Aegypius calvus, e.g., Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2005) and Rasmussen and Anderton (2005). This the only species of the Genus Sarcogyps (Lesson 1842). Currently, no subspecies have been recorded. Based on nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene, Seibold and Helbig (1995) found that within the clade of the Old World vultures including the genera Aegypius, Gyps, Sarcogyps, Torgos, and Trigonoceps, this species was consistently excluded from the clade including the other three genera. This hinted that it might be the most primitive of the group. Wink (1995) also found that this species belongs to this clade of Old World vultures.

Other authors, namely Amadon (1977), Stresemann and Amadon (1979) and Amadon and Bull (1988) argued that the four monotypic genera of large Old World vultures, due to morphological closeness should be placed within one genus, Aegypius (as also noted by Seibold and Helbig 1995; Wink 1995). However, not all authors agree, and sometimes the Red Headed vulture is placed in the Genus Torgos Kaup, 1828, with the Lappet-faced vulture Torgos tracheliotos Forster 1791.

Foraging. The Red-headed vulture is usually more solitary than other vultures (Ali and Ripley 1983; Kazmierczak 2000). It forages in open, mixed vegetation landcover, often close to human habitation, and also more forested landcover such as hilly and dry deciduous forest, usually as a single forager rather than as a flock like the Gyps vultures (Roberts 1991; Grimmett et al. 1998; Robson 2000). Chhangani (2007a) in a study of Rajasthan, India, noted 'a strong correlation' between the presence of vultures and mammalian carnivores such as tigers (Panthera tigris Linnaeus 1758), leopards (Panthera pardus Linnaeus 1758) and Indian wolves (Canis lupus pallipes Sykes 1831) in their study area, as vultures fed on the predators' kills.

Despite the common perception that this species prefers mixed vegetation and dry forest, Nadeem et al. (2007) recorded a pair in the Khairpur area in the Tharparker Desert, a location covered by desert, shrub vegetation such as Calligonum polygonoides (L.), Aerva javanica ((Burm.f.) Shult), Cymbopogon jwarancusa (Jones), Haloxylon salicornicum ((Moq.) Bunge ex Boiss), Dipterygium glaucum (Decne), Leptadenia pyrotechnica ((Forssk.) Decne), Calotropis procera ((Aiton) W.T. Aiton) and small to medium-sized trees such as Prosopis cineraria ((L.) Druce) and Salvadora oleiodes (Decne, Ziziphus mauritiana Lam.) and Acacia nilotica ((L.) P.J.H. Hurter and Mabb). They describe this as the first sighting of this species in Pakistan since 1980, and also 'This characteristic plant community has not previously been recorded as a preference of this vulture, which has never before been reported, even as a transient, from such deep desert areas' (Nadeem et al. 2007: 146). It is hypothesized that vulture presence in this desert was due to food shortages and increasing urbanisation in more favored habitats.

Breeding. Red-headed vultures generally nest on large- and medium-sized trees. In the study by Chhangani (2007a) in Rajasthan, India, nests were located in the following tree species: Khejri Prosopis cineraria (L.) Druce (3-5 m tall), Babul Acacia nilotica (L.) P.J.H. Hurter & Mabb (5-20 m tall), Rohida Tecomella undulata (D. Don) (up to 12 metres tall), Ficus Ficus benghalensis L. (20-25 m tall) and Godal Lannea coromandelica (Houtt.) and Merr (up to 14 m tall). Nesting density may be low, as unlike many other vulture species it is very territorial and is not gregarious (Naoroji 2006). It usually lays a single egg (Fig. 2.5d).

Population status. The distribution of the Red-headed vulture is shown in Fig. 2.5e. Redheaded vultures are described as rare; even historically and globally it was 'nowhere very abundant' (Blanford 1895; see also Bezuijen et al. 2010). Chhangani (2007a: 220) noted that in Rajasthan 'sightings of Red-headed vulture were fewer than those of Long-billed, White-backed or Egyptian vultures. Most sightings of Red-headed vultures were of solitary birds or breeding pairs, or of birds at feeding sites.' Other authors report similar results from Gujarat (Khachar and Mundkur 1989), and recently with population declines it is increasingly rare (Chhangani 2004, 2005, 2007b; Chhangani and Mohnot 2004).

The population reduction has been very rapid, due to feeding on animal carcasses treated with the veterinary drug diclofenac, and possibly other contributory factors, leading to its classification as Critically Endangered (BirdLife International 2014). Cuthbert et al. (2006) calculated a decline of over 90% within 10 years in India. Factors included habitat loss, disturbance, predation, hunting, road accidents when feeding, food and water scarcity, land use change and poisoning (Chhangani 2002, 2003, 2005). Other authors record a decline in other Asian nations such as Pakistan (Nadeem et al. 2007); Bhutan and Burma (Bezuijen et al. 2010; Hla et al. 2011), China (Chan 2006); Thailand (Round 2006), Laos, Vietnam, peninsular Malaysia, Singapore (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). Possibly in Cambodia the population is stable since 2004 (Eames 2007a,b).

Doloh (2007: 79) describes a five-year joint programme by Kasetsart University (KU) and the Zoological Park Organisation (ZPO) to rescue the 'near extinct' Red-headed vulture in the forests of Uthai Thani, Thailand. This concerns a breeding and reintroduction programme to release the birds back into the wild. It is noted the 'the last big flock disappeared in early 1992, after eating a poisoned deer carcass. The carcass had been contaminated with toxic chemicals by tiger hunters using the deer as bait' (Doloh 2007: 80).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 248;