Forest Vultures: Olfaction and Carrion Detection in Tropical Forests

Vegetation is a very important factor for vulture foraging and nesting. There are many classifications of global vegetation patterns. One of the most comprehensive is that of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), which recognizes 14 biomes, where a biome is a region of similar climatic conditions with associated communities of animals and plants (Olsen et al. 2001). From the perspective of vultures, there are five particularly important biomes: Biome 1, Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests; Biome 2, Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests; Biome 7, Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands; Biome 8, Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands; and Biome 10, Montane grasslands and shrublands (alpine or montane climate). Biome 13, the deserts, is also considered, as in some cases vultures may follow migratory ungulate herds or livestock herd across deserts and very dry savannas, especially in Africa.

The main issue for vultures in relation to these biomes is the ability to detect food. For the Old World vultures that lack a sense of smell and forage by sight, it is necessary to see the carcasses upon which they feed. For this reason almost all the vultures in Africa, Asia and Europe are absent from closed canopy forest. For some New World vultures, which do have a sense of smell (the Cathartes species), or weak or no sense of smell but can follow the Cathartes species to carcasses (the other New World vultures), the issues are both sight and smell. Hence, these species may be found in both forest and open cover. The first landcover discussed is forest, followed by the tropical savanna and desert, then the temperate grassland and montane vegetation.

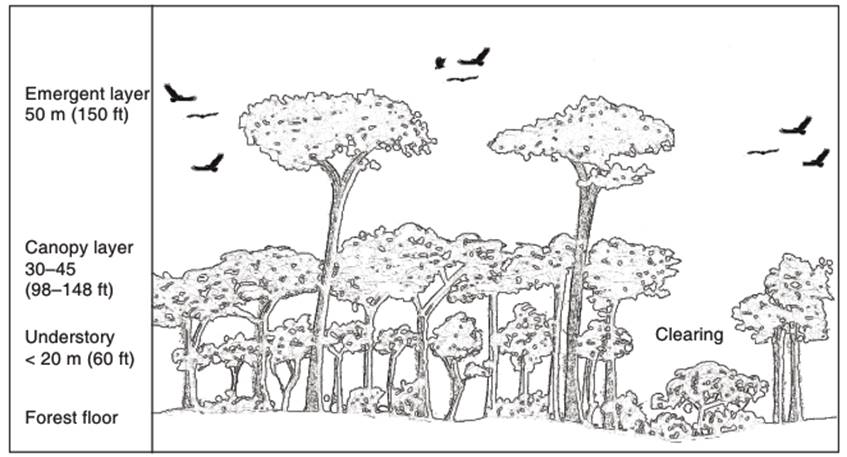

Biomes 1 and 2, the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests and the drier tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests are characterized by high rainfall and in the case of the drier zones, a dry season. Tropical rainforests have warm and wet climates, with the mean monthly temperatures exceeding 18°C (64°F) during all months of the year and the mean annual rainfall usually between 175 cm (69 in) and 200 cm (79 in). Some rainforests have very high rainfall, with annual rainfall between 250 cm (98 in) and 450 cm (180 in). There are generally four layers in the rainforest: the emergent, canopy, understorey and forest floor layers. The emergent layer is composed of emergents; a few very tall trees growing above the canopy, usually reaching heights of 45-55 m. The canopy layer is composed of the majority of the larger trees, usually between 30 (98 ft) and 45 m (148 ft) in height, forming a continuous cover of foliage. The understorey layer is composed of smaller, shrub-sized plants between the canopy and the forest floor. The forest floor has plants adapted to lack of sunlight, as only a small amount of light can pass through the dense canopy. Where a gap appears in the canopy, due to a blowdown in a storm, a forest fire or human action, the sunlight reaches the forest floor and usually contributes to a dense growth of shrubbery, grasses and saplings. Eventually, a new canopy may emerge (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.4. Forest Structure Layers

Vultures may not be able to see through the canopy to carcasses on the forest floor. Due to this difficulty, the ability to scent carcasses is important. Most vultures, unfortunately do not have a developed sense of smell. For this reason vultures are rare in forests, and all vultures except the Cathartid species hunt by sight rather than smell. As pointed out by Houston (1986: 318) 'forested areas of Africa or Asia do not support scavenging birds, while neotropical forest is the center of distribution for the cathartid vultures.' In addition, 'Turkey vultures have a well-developed olfactory lobe and sense of smell which is used for finding food in forested areas...' therefore the Turkey Vulture and '.... the closely related Greater Yellow-headed vulture are the commonest vultures of neotropical forests' (see also Chapman 1929, 1938; Bang 1964; Stager 1964).

The close link between dense vegetation and olfaction or sense of smell in vultures, and disputes as whether vultures use sight or smell or both, have been recorded in the literature for more than a century. From the 19th century, researchers and debaters included Barrows (1887), Hoxie (1887), Sayles (1887) and Hopkins (1888). The debate continued into the early 20th century (see for example Taylor 1923; Leighton 1928; Lewis 1928; Earl 1929; Darlington 1930; Coles 1938; Vogt 1941; Rapp 1943). Studies hovered between belief in the birds' use of sight or use of olfaction, or both and used sometimes crude experimentation methods. Later studies were more sophisticated, using detailed biological examination and rigorous ecological assessments (such as those of Owre et al. 1961; Barros Valenzuela 1962; Stager 1964; Bang and Cobb 1968; Fischer 1969; Bang 1972; Wenzel and Sieck 1972; Houston 1982, 1987, 1990, 1994; Smith et al. 1986; Applegate 1990; Graves 1992; Gomez et al. 1994; Smith et al. 2002; Ristow 2003; Gilbert and Chansocheat 2006). The eventual concensus of these studies was that the Cathartes vultures were able to locate food by smell, while the other New World vultures were unable to do so, as they either had a weak sense of smell or none.

Vultures in forested areas use low flight just above the canopy, using the rising air on the windward side of tall emergents. Only when they detect food do they descend below the canopy, where they are agile, flying between the branches or even walking on the ground. To test the ability of Turkey vultures in detecting carrion in dense rain forest, Houston (1986) placed carcasses in different places in a dense forest in Panama, with varying visibility from the sky, some invisible under leaves, and at various stages of decay (fresh, one-day and four-day old carcasses) on the hypothesis that the birds used both vision and smell. Also recorded was the time taken for other scavengers to find the carcasses, as the success of the vultures would also depend on arriving at the carcass before other ground-based species. Dead chickens were used, partly because they are similar in size to normal vulture food, such as dead opossums, sloths and small monkeys.

The results of this study showed no correlation between carcass detection-time for vultures and the size of the gaps in the canopy. Also, there was no significant difference in vulture detection time for exposed carcasses and carcasses covered by leaves. For the age of carcasses, fresh carcasses were significantly more difficult than one-day old carcasses for vultures to detect, but there was no significant difference between a day- old and four-day old carcasses in speed of discovery (although there was a slight, but insignificant preference for the one-day old carcass over the four-day old carcasses). Turkey vultures consumed the bulk of the carcasses, followed by Black vultures, which arrived long after the Turkey vultures in larger numbers and were dominant in conflicts. A few mammals, such as opossums (Didelphis marsupialisa, Linnaeus 1758) and coatis (Nasua nasua, Linnaeus 1766) were also seen at the carcasses. 'The results show smell to be the major sense used by Turkey vultures to locate carrion and puts vision in a minor role, for completely hidden food was found as quickly as visible bait' (Houston 1986: 321). This author also wrote that 'Black Vultures do not have a sense of smell, and my observations in other study areas have shown that they are not found in undisturbed forest and cannot locate food in forest conditions unless led there by Turkey vultures' (ibid. 322).

In another study in dense forest in Venezuela, Turkey vultures or Yellow-headed vultures arrived first at carcasses, while groups of Black vultures were the most likely to arrive at large carcasses or carcasses in more open vegetation. King Vultures were recorded as equally likely to arrive at large or small carcasses. Turkey vultures were less aggressive than Black vultures and usually subordinate to Black vultures in aggressive interactions at carcasses (Stewart 1978; Wallace and Temple 1987; Houston 1988; Buckley 1996; Buckley 1998).

Another denizen of the forest is the Greater Yellow-headed vulture, often named the 'Forest vulture' to distinguish it from the Yellow-headed vulture or 'Savanna vulture.' Found in the dense forests of South America, it rarely roams into open country (Hilty 1977). This species flies low over the canopy, detecting small carcasses on the forest floor and along rivers (Robinson 1994). In the forested Amacayacu National Park, Colombia found this species was the most abundant vulture and usually the first to locate a carcass, in both in open clearings and under canopied forest (Gomez et al. 1994). These vultures located 63% of provided carcasses, while mammalian scavengers found only 5%. The Greater Yellow-headed vultures were however displaced from carcasses by Turkey vultures and King vultures.

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 258;