Fungi as Modular Organisms

Fungi characteristically grow as a network of branching tubes (hyphae), collectively called a mycelium (Andrews 1995; Bebber et al. 2007). Knowledge of fungal architecture and hyphal growth patterns has been obtained almost exclusively from laboratory culture of representative ascomycetes and basidiomycetes (and prokaryotic actinomycetes) on solid nutrient media (Harold 1990; Riquelme et al. 2011). From these relatively uniform and highly controlled conditions the following general pattern emerges. Hyphae initiated from a germinating spore grow radially outwards, branch, occasionally fuse, and show mutual avoidance reactions (Gow et al. 1999; Glass et al. 2004). As long as growth remains unrestricted, the ratio between total hyphal length and number of branches eventually becomes constant for any particular strain, a value referred to as the hyphal growth unit (Trinci 1984; Trinci and Cutter 1986). (This phenomenon, incidentally, is characteristic of branching systems in general and is not unique to fungi.)

Thus, under ideal conditions, the mycelium can be regarded as resulting from duplication of this hypothetical growth unit comprising a hyphal tip and an associated growing mass of constant size. Conceptually, this is a convenient vegetative module, as is the leaf and its axillary bud a unit of plants. Most fungi (and actinomycetes) go on to produce other forms of vegetative (asexual spores) and sexual modules, just as plants develop vegetative modules that are later alternated with or replaced by sexual modules such as flowers, stamens, and carpels. Superficially similar branching patterns are evident among other sessile organisms such as the stoloniferous colonies of the marine hydroid Hydractinia (Buss 1986). Details of the fungal architecture and the case that fungi are modular organisms are discussed at length in Andrews (1994, 1995).

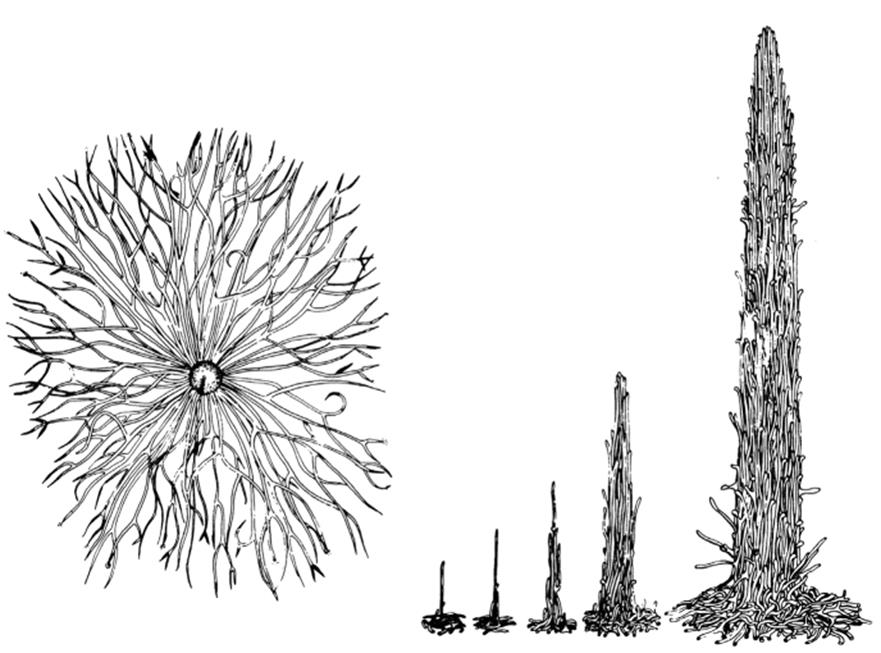

While in its diffuse feeding mode the branching mycelium is conspicuously modular in construction, it can differentiate to function in two other roles, namely survival and reproduction/dispersal. In both cases, hyphae that were formerly kept separate by some repulsive mechanism come together under control to produce aggregated structures (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3. Fungi as modular organisms. Left, Achlya, a so-called water-mold (technically a member of the Phylum Oomycota, studied by mycologists but not phylogenetically a 'true' fungus) growing in diffuse fashion, allocating biomass primarily to foraging hyphae (from Bonner 1974, p. 97; redrawn from J.R. Raper). Right, Pterulagracilis, a basidiomycete, growing as an aggregate hyphal unit in the process of forming a fruiting body, allocating biomass primarily to reproduction. From Bonner (1974, p. 96; redrawn from E.J.H. Corner). Reprinted by permission from On Development: The Biology of Form by John Tyler Bonner, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, copyright ©1974 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

These forms often have architectures unlike anything else on earth. The frequently complex and massive fruiting bodies (basidiocarps) of the basidiomycetes represent the extreme in such morphogenesis. In such cases the mycelium performs a structural and transport function; here it plays no role in nutrient uptake, serving only to provide an exposed surface for spore dissemination. In some (including the common mushrooms), the basidiocarps (fruiting bodies) are fleshy, transient, and rely mainly on turgor pressure for support. In contrast, those of the bracket fungi are large, and may be crust-like or woody and perennial (Phellinus, Ganoderma).

Specimens of the well-known ‘artist’s conk’ (Ganoderma applana- tum) are recorded up to 1 m across and approximately 10 kg. In this sense they are analogous to trees in accumulating structural dead biomass. The important generality with respect to architecture is that the fungi seem to exploit two major patterns: a branched, foraging mode, and one that is organized and consolidated for reproductive or other purposes. That substantial biomass can be diverted away from resource acquisition to survival or reproductive structures attests to the importance of dormancy and relatively long-range dispersal of new genets, as opposed to localized growth by mycelial extension, in the life histories of these fungi (see also Chaps. 6 and 7 and Andrews 1992).

Date added: 2025-06-15; views: 205;