Hurricanes and Typhoons: Increasing Intensity and Climate Change

Hurricanes and typhoons are large tropical cyclones—rotating storm systems that develop in the tropics, involve low atmospheric pressure and sustained high winds, and result in heavy rains. Different terms for such storms are used in various parts of the world, and a further set of terms is applied to systems of lesser intensity.

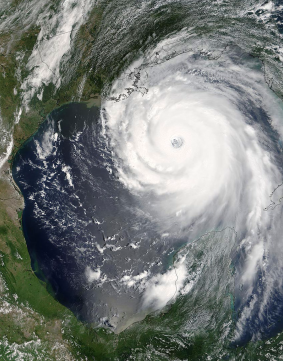

Tropical cyclones derive their energy from the warm oceans over which they form. An “eye” of light wind, clear sky, and low atmospheric pressure, usually 20 to 40 miles wide, lies at the center of the system and is surrounded by an “eyewall” of very strong winds. Long strands of thunderstorms known as “rainbands” spiral out from the center of the cyclone, and the system itself can reach hundreds of miles in diameter. To be called a hurricane or typhoon, the storm system must involve sustained winds of at least 74 miles per hour (mph), although winds can reach much higher speeds, particularly in gusts. Such systems also create storm surges, potentially raising sea levels by more than 20 feet.

A satellite view of Hurricane Katrina, August 28, 2005. One of the most powerful storms to ever strike the United States, Katrina was a Category 5 hurricane that sustained winds of 160 miles per hour with even stronger gusts. The number of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes has almost doubled in the last thirty years, a fact that some climate experts attribute to global warming, specifically the rise in ocean surface temperature (Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC).

Due to the Coriolis effect, cyclonic systems rotate counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern. Although the long-range movements of hurricanes and typhoons are difficult to predict, their paths are generally determined by a combination of global winds and high- and low-pressure systems. Such storms gradually lose strength when they move over land or cooler water.

The term “hurricane” is applied to a large tropical cyclone in the North Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the North Pacific Ocean east of the international date line (generally 180 degrees longitude), and the South Pacific Ocean east of 160 degrees east. Such a storm is called a “typhoon” in the North Pacific Ocean west of the dateline. The term “severe tropical cyclone” is used in the South Pacific Ocean west of 160 degrees east and the Southern Indian Ocean east of 90 degrees east. A similar storm is referred to as a “very severe cyclonic storm” in the Northern Indian Ocean and a “tropical cyclone” in the Southwest Indian Ocean. When the sustained winds of a tropical cyclone are between 39 and 73 mph, the system is known as a “tropical storm,” and when the maximum sustained winds drop below 39 mph, it is termed a “tropical depression.”

Tropical Cyclone Olivia holds the record for the highest wind speed for such storms, generating a gust of an astonishing 253 mph and creating waves 69 feet high off the northwestern coast of Australia in 1996. After forming over the western Caribbean in 2005, Hurricane Wilma set a record for the fastest drop in atmospheric pressure in a given period. Its eye also contracted to 2.3 miles in diameter, the smallest on record for a hurricane in the Atlantic Basin.

Over the centuries, large tropical cyclones have inflicted enormous damage and resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of people. Hurricanes are ranked on the five-category Saffir-Simpson Damage Potential Scale, which measures the estimated flooding and property damage they may cause. According to this system, Category 1 hurricanes involve sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. At the top of the intensity scale, Category 5 hurricanes produce winds of 157 mph and greater. Hurricane Katrina, for instance, which struck the southeastern United States in 2005, generated winds of 175 miles per hour, devastating the city of New Orleans and resulting in more than 1,800 fatalities. It was also the costliest such storm in the nation’s history, inflicting some $125 billion in damages. Since its development in 1973, the Saffir-Simpson Damage Potential Scale has been adapted and used by the weather services of Australia and Japan.

Large tropical cyclones were named for the first time in the late nineteenth century in Australia. Although it took other nations, including the United States, some time to adopt the practice, giving names to such storms is routine in the early twenty-first century and allows for fast and easy reference in times of emergency.

Climate change impacts the formation and intensity of hurricanes and typhoons in several ways. Warming ocean surfaces are one of the components leading to the creation and fueling of such storms. For instance, it is estimated that since 1970, twice as many storms have reached the top of the Saffir-Simpson scale (4 to 5). Some scientists even suggest adding a new category—six—to both reflect and alert to the increasing intensity of hurricanes. This category would apply to tropical storms with wind speeds exceeding 192 miles per hour. Similarly, warmer water leads to warmer surrounding air, allowing storms to absorb more moisture and release more water once they land. This release could cause more significant and more destructive flooding. Lastly, sea-level rises could trigger increasing storm surges that greatly endanger coastal communities.

FURTHER READING: Brinkley, Douglas. 2006. The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. New York: Morrow.

Emanuel, Kerry A. 2005. Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Longshore, David. 1998. Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones. New York: Facts on File.

Schwartz, Stuart B. 2015. Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;