The Demographic Transition Model

Our discussion of population growth rates and population pyramids illustrates a strong association between population growth and economic development. Highly developed countries have low rates of population growth, while less developed countries tend to grow rapidly. The demographic transition model accounts for the fact that high rates of population growth in the world today are concentrated in the less developed countries.

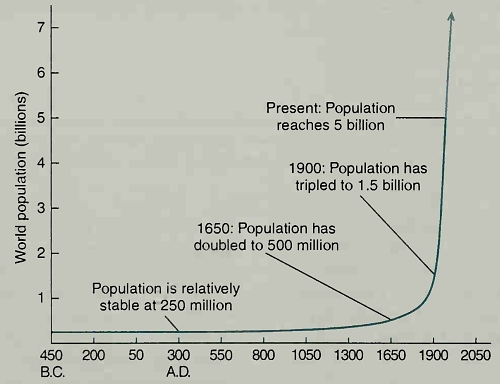

In 1991. the world's population was increasing by approximately 1.7 percent per year. Only during the past three centuries, however, has global population growth occurred at this rapid a rate (Figure 3-6). This recent global population explosion stands in sharp contrast to previous history when the world's population grew only slowly. It has been estimated that two thousand years ago, the world's population numbered 250 million—a figure roughly equivalent to the population of the contemporary United States. Not until 1650 did the population double, reaching half a billion.

Figure 3-6. World Population Growth. The world's population has increased dramatically during the past three centuries, and the rate of natural increase has also risen. Much of this increase can be attributed to falling death rates relative to birth rates. Will birth rates throughout the world eventually fall in order to match current death rates? Will death rates rise if overpopulation strains the global resource base?

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the world's population began to increase rapidly in connection with the Industrial Revolution. By 1900 it had tripled to 1.5 billion, and in the twentieth century population growth has been still more rapid. The current population of the world is estimated at over 5 billion, and it may reach 6 billion by 2000.

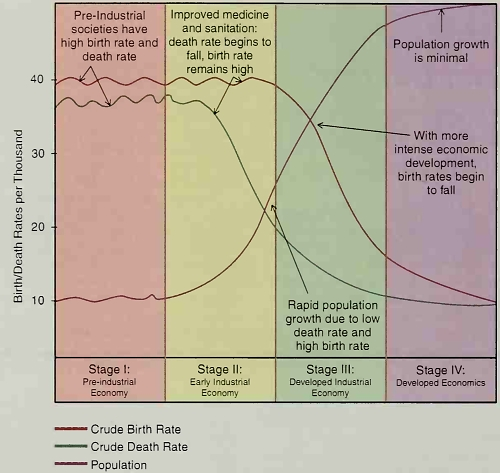

Demographic transition is the process by which birth and death rates change. One interpretation is that this change is a response to industrialization and technological development. In preindustrial societies, birth and death rates were both substantially higher than they are today. As industrialization proceeded, death rates began to fall while birth rates remained elevated. Eventually, birth rates also begin to fall, approaching already low death rates.

The fact that death rates fall before birth rates decline yields four stages in the model (Figure 3-7). Large-scale population growth is concentrated in the second and third stages, when birth rates are substantially greater than death rates. At the first and fourth stages, birth and death rates are roughly equal, and population growth is minimal. Today, no countries remain in the first stage. Less developed countries are in the second and third stages, while the Western industrialized countries are in the fourth stage.

Figure 3-7. The Demographic Transition Model. The demographic transition model relates changes in a country's rate of natural increase to levels of economic development. Rapid population growth occurs during transition from pre-industrial self-sufficiency to an increased integration into the world economy. The model predicts that rates of natural increase will begin to decline as development proceeds

The First Stage. The high birth and death rates associated with the first stage of demographic transition were found in preindustrial societies throughout the world. Records from Europe, even as late as one hundred years ago, illustrate that both birth and death rates were considerably higher.

The high death rates of preindustrial societies fluctuated considerably. The major causes of death were famines and epidemic diseases that killed large numbers of people periodically. Doctors who lacked modern knowledge of medicine, sanitation, and public health were powerless to treat epidemic diseases that ravaged medieval Europe. An epidemic of the "Black Death" or bubonic plague killed approximately a quarter of Europe's population during the fourteenth century.

Many other people died during famines caused by crop disease, drought, freezing, or excessive rainfall. Famine also decreased individual resistance to disease. Over the long run. however, birth rates tended to equal death rates. Populations of most pre-industrial societies were stable, or grew only at slow rates.

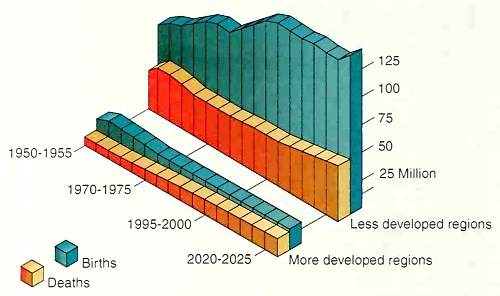

The Second Stage. The transition from the first to the second stage was marked by a rapid decline in the death rate, while the birth rate remained high (Figure 3-8). As a result, populations grew rapidly. Europe and the United States moved into the second stage in the nineteenth century, while the less developed countries have done so only recently (Figure 3-9).

Figure 3-8. The Excess of Births over Deaths. Between 1950 and 1955. the annual number of births in the less developed regions exceeded deaths by 36 million. By 2020-2025 the gap is expected to widen to 80 million. In the more developed regions, there were 11million more births than deaths in 1950-1955. By 2020-2025 the number of births in these regions is expected to exceed deaths by only 2 million a year

Figure 3-9. Stage Two Family. The second stage of the demographic transition is characterized by high rates, partly due to a high rate of infant mortality. As such, parents in this stage are encouraged to have several children in order that some will survive to adulthood. Thus, this stage two family from Peru is rather large

Death rates declined during the second stage because of the development and diffusion of modern scientific medicine. Scientists discovered causes and cures for epidemic diseases and developed vaccination and inoculation techniques to prevent their further spread. Improved sanitation, nutrition, hygiene, and public health reduced the frequency and magnitude of epidemics and contributed to a major decline in infant mortality.

Birth rates at the second stage remain high and may be derived in part from high rates of infant mortality. Parents are often encouraged to have several children in order to ensure that some will survive and be able to care for their parents in their old age. Children go to work when they are still very young, increasing the incomes and productive capacities of their families. In the developed countries, on the other hand, child labor is restricted or forbidden by law. Children remain dependent on their families longer, and the cost of raising and educating children increases, providing an economic incentive to have smaller families.

In regions at the second stage of demographic transition, alternatives to early and frequent childbearing are few. Educational and employment opportunities are not readily available to women in less developed countries.

Many remain under considerable social pressure to stay at home in order to raise large families. Furthermore, many lack access to birth-control and family-planning information and resources.

The Third Stage. Rates of natural increase are highest at the second stage of demographic transition. Eventually, declining death rates are followed by declines in birth rates. Once a country's birth rate begins to fall, it moves from the second to the third stage of demographic transition (Figure 3-10).

Figure 3-10. Stage Three Family—China and Birth Control. Birth rates decline as a country moves from the second to the third stage of the demographic transition. The reasons for the declining birth rate may include such factors as government persuasion. China, for example, launched a controversial "one-child" campaign in order to reduce China's birth rate

While many of the less developed countries remain in the second stage, several have moved into the third stage. China made a concerted effort to reduce its population by encouraging later marriages and penalizing couples for having more than one child. The reduction in China's birth rate resulting from this controversial policy moved that country from the second to the third stage.

At the third stage, people decide to have fewer children. Increased social and economic opportunities for women, alternatives to the rearing of large families, increased costs of bearing and raising children, and the obsolescence of children as social security are partly responsible for these declining birth rates. Often, lowered birth rates are associated with the transition from an agricultural to an industrial society. Most countries with low agricultural densities have entered the third stage of the demographic transition.

The Fourth Stage. As demographic transition proceeds, birth rates continue to fall until they approach already low death rates. Eventually, the fourth stage of the model is reached. At this stage, birth and death rates are both low. This final stage is characteristic of Europe, North America, and other highly developed economies.

Death rates in the industrialized countries are lower than at any time in history. Recently, the United States Bureau of the Census announced that a baby born today can expect to live seventy-five years—the highest life-expectancy figure in history. Medical science is continuing to make progress in combating heart disease, cancer and other major causes of death. Birth rates are lower than at any time in history. More and more people are postponing childbearing. and many elect not to have children at all. Families of five or more children, once commonplace in the United States and Europe, are becoming increasingly unusual.

Date added: 2023-01-14; views: 851;