Processing. Characteristics of Trust and Control

Processing. The model itself does not mandate any particular method of processing evidence into the decision regarding confidence. Even though such processing may be (and often is) quite subjective, we can identify certain common traits that are applicable probably not only to the decision regarding confidence but to our decision-making process in general.

Giddens [Giddens1991] has noticed that the rules that we use to assess confidence fall into two categories, depending on our previous experience and depending on available complexity. Reflexive rules form an automatic behaviour that delivers satisfactory assessment rapidly and with low cognitive complexity. They are formed mostly on the basis of existing experiences (stored patterns that can be recalled when needed) and works almost as a set of ready-made behavioural templates.

Reasoning rules allow us to handle more complex cases at the expense of complexity and time. Here, our reasoning capability is invoked to rationally deal with available evidence, by exploring through reasoning. The process is quite slow, restricted in its maximum complexity and may require significant mental effort. As such, it cannot apply to known situations that require rapid decisions but works well for situations that are new or unexpected.

Specifically, the appearance of evidence that contradicts existing knowledge may trigger the transition from reflexive to reasoning rules. Similarly, the repetitive appearance of similar evidence may lead through the learning process to the creation and use of the new reflexive rule.

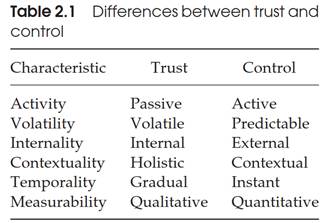

Characteristics of Trust and Control. When considering modern society one cannot resist the feeling that control has the upper hand and trust is diminishing. However, instead of lamenting the destruction of trust it is worth considering why society so often chooses the control path, despite its obvious higher complexity.

The answer (at least partly) lies in the different perceived characteristics of control and trust, captured in Table 2.1. The concept of 'two trusts' provides a certain insight in it, but there is more detailed discussion that highlights differences between control and trust. The understanding of those differences may lead not only to the better understanding of the skewed balance between trust and control, but also may show methods to re-balance it.

Modern culture has re-defined the concept of risk [Giddens1991]: from risk associated with individual actions and encounters to pervasive risk that is reduced and at the same time increased by the existence of intermediating institutions. The shift in the allocation of risk results in the shift in the way confidence is evaluated - towards control. If there is not a sufficient amount of trust-related interactions, then the demand for increased control is the only possible solution.

We start from an observation [Giddens1991] that modern life favours rational knowledge, doubt and critical reasoning - to the extent where everything can be questioned. This leaves less space for belief-based expectations (trust in this case) that cannot be critically questioned and rationally deconstructed. Control, on the other hand, can usually withstand rational analysis (unless we start questioning foundations of such control, i.e. trust in instruments), so that it seem to be more appropriate for modern life.

Activity. Trust caters for Alice's own inactivity as the assumed goodwill of the trustee should itself facilitate the positive course of actions regardless of her own activity. When Alice is relying on Bob's internal trustworthiness, the only thing that she has to do is inform Bob about her needs - as Bob cannot be expected to act upon her needs if he is not aware of them. This can be delivered reasonably simply and does not require any specific tools (even though it may require certain determination if Bob is not readily accessible).

Control is closely related to the preparedness and readiness to act, possibly rationally and in the pre-planned manner. By considering control Alice accepts that she may not only contemplate evidence but may also perform an actual action. Note that control is not only about action itself - Alice may never be required to perform any action regarding Bob. It is about her confidence that she (or someone else) is ready to act if needed - with the expected result.

Volatility. Trust has a high volatility. If Alice trusts, then she potentially exposes her vulnerability to Bob and becomes subject to his behaviour - she becomes dependent on Bob. Trust is essentially the exchange process where the uncertainty of the world is replaced by the uncertainty of the single person - the trustee. By trusting, we are entirely dependent on the behaviour of an individual that we cannot control. Such an individual becomes the single point of failure of the process - if he defaults, we have nothing to protect ourselves with.

Control, stressing differences, is a piecemeal decision with space for plenty of recourse and consequently with low volatility. One can build an elaborate system of control (within the limits of disposable complexity) so that even if one part of such system fails, other parts will hold and deliver at least a partial result. Uncertainty can be spread among several entities and there is no single point of failure. The system is still fallible, but it is a graceful degradation, not a total disaster.

Internallty. Control requires instruments that are usually external to the relationship. Certainly Alice can control Bob directly (say, the way mother exercises control over her child), but this situation is unlikely, as it consumes too much of Alice's resources (what every mother would experience from time to time). She will rather seek instruments of control that can be summoned to help her if needed.

Alice must be ready to bear the burden of dealing with those instruments, as they must be included in her horizon. If, for example, she considers controlling Bob through the judicial system, she is facing the complexity of understanding and applying the law. While the task may seem daunting, the institutionalisation of our world means that Alice has a rich set of instruments to choose from, making control attractive.

In contrast, trust is internal to the relationship between Alice and Bob as much as trustworthiness in internal to Bob. Acting upon Bob with certain instruments may actually have a detrimental effect on his trustworthiness. Trust, not dependent on any instrument external to the relationship, develops by Alice's actions and observations within such a relationship.

Contextuality. Trust is considered to be the quality of an agent that permeates its behaviour across all the possible context. Trustworthy Bob is supposed to be trustworthy at work as well as at home, in the train, etc. Trusting Bob means knowing Bob across all those contexts - quite a task, specifically if Alice has no time for this or no interest in this. Even the most contextual element of trust - competence - may require a holistic approach to assess it correctly.

Control is narrowly contextual - Alice would like to control Bob here and now, with disregard to the future. Actually, as control is built on instruments that are external to Bob, Alice can rely on those instruments without even knowing Bob, but only knowing the environment he operates in [Giddens1991]. By gaining expertise in environmental instruments, Alice can swiftly build up a passing relationship not only with Bob, but with anyone who is controlled in a similar manner. Relying on control allows Alice to roam freely.

Temporality. Control is useful for short-term encounters, where Alice has no interest in the common future. It is not only that Alice cannot reliably coerce Bob into a long-term relationship, but it is also that the continuous control of Bob will eventually drain her resources. However, on the bright side, control is an instant mechanism: Alice does not have to engage in complex observations or interactions prior to the transaction. She can quickly build control on the basis of instruments, even though such control may not last.

In contrast, if Alice wants to build trust with Bob, she should possibly employ her empathy [Feng2004] and build a relationship over time. Even though such a relationship may benefit her in the longer time frame, it effectively locks her into Bob, as she has neither time nor resources to nurture alternative relationships. In a marketplace of disposable relationships that does not value loyalty and continuously entices customers with new offers, there is little place for the proper development of trust. As the time horizon of the relationship shrinks, the ability to nurture such relationship also decreases.

Measurability. Yet another reason why trust seems to be unpopular is the lack of a reliable way to quantify trust. Control has developed several methods to measure probability, risk or the financial outcome of control-based transactions, leading to greater predictability and accountability (conveniently ignoring trust in instruments of control). Trust is unfortunately devoid of such methods, as measuring intentions is neither straightforward nor reliable.

The concept of risk is well known in businesses and there is a large body of knowledge dedicated to methods related to the assessment of risk. Therefore, even though risk itself is not avoidable, it can be well predicted - and consequently it can be factored into the business model, e.g. in a form of higher charges or additional insurance. Over time, for a reasonably stable business, risk becomes a well-known, predictable factor, part of a business as usual.

Trust does not yield itself to calculations (at least not yet). Dealing with individuals and with their internal intentions is associated with high level of uncertainty, thus increasing the volatility and decreasing the predictability of the outcome. From the business planning perspective, greater known risk is a safer bet than possibly a lower but unknown one, so businesses make a rational decision to prefer control over trust.

Digital Technology. An important reason for the shift from trust to control-based relationships is the development of technology. Society has developed and is still developing significant amount of instruments of control at the high level of sophistication, at a relatively low price and relatively easy to use. Technology (specifically digital technology) has been particularly supportive in creating new tools of control. All those instruments are designed to decrease the need for trust. However, they are actually increasing the need for trust, but for another trust - trust in instruments.

Offsetting trust in people with trust in digital tools might have been a valid option, as the total complexity has initially decreased. However, as those tools rely on trust (in the system administrator, in the infallibility of digital technology), the long-term complexity may be quite high, which is evident e.g. in the growth of time that we spend protecting our computers from attacks.

However, the path of control, once taken, cannot easily be undone, specifically when traditional relationships of trust have been abandoned as no longer relevant or modern enough. The only choice, it seems to be, is to proliferate tools of control up to the level where we collectively will not be able to control tools that control us. If this is not the desired future, some alternatives will be discussed throughout in this book.

Date added: 2023-09-23; views: 636;