Strategies Using Iron Supplements

Efforts to improve nutrition in vulnerable groups have been attempted in the past, but it was not until 1990 that UNICEF gathered political leaders and concerned organizations from many countries at the World Summit for Children to establish policies focused on reducing iron deficiency in children, with the aim to decrease to one-third the prevalence of IDA in pregnant women.

Later, in 1992, the goal of addressing the high prevalences of anemia, affecting particularly children and pregnant women, was reiterated. In subsequent international forums and meetings, those goals were confirmed (UNICEF, 2004; Allen et al., 2006).

Supplementation is the most frequently recommended method to address iron deficiency and limited iron intake (The Manoff Group, 2001) “Supplementation is the action of supplying relatively high doses of micronutrients in the form of syrups, pills, and capsules. Supplementation furnishes optimal quantities of micronutrients in a highly absorptive presentation’’ (Allen et al, 2006: 3-20).

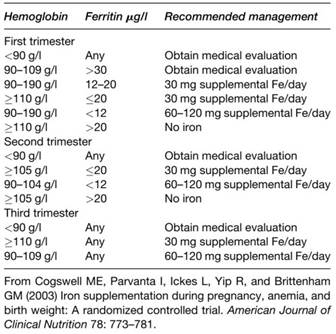

Nevertheless, implementing a supplementation program is not easy. First, the quantity of supplemented iron must be established so as not to exceed the amount of required iron. The Institute of Medicine of the United States has produced a supplementation guide specific for pregnancy (Table 6). Secondly, a reliable system of distribution must be set up. Adherence to the consumption of supplements by the target population is also essential, particularly when supplements are to be consumed for long periods (Cogswell et al., 2003; Allen et al., 2006).

Table 6. Summary of Institute of Medicine (IOM) Guidelines for Iron Supplementation during pregnancy

Faulty distribution of supplements and low adherence are the main obstacles for the success of supplementation programs (Allen etal, 2006). Several recommendations have been proposed to improve the adherence to supplement consumption, for instance, encouraging consumption and educating people about the benefits of supplementation, and using iron supplements with a low rate of adverse gastrointestinal effects.

A study conducted in India among women who consumed 60, 120, and 240 mg of iron/day reported adverse gastrointestinal effects in 32%, 40%, and 75% of cases, respectively, concluding that adverse effects increased as iron doses increased. It is possible that people experiencing more adverse effects are less likely to adhere to supplementation.

There is some controversy as to the most adequate frequency of dosing with iron supplements. Beaton and McCabe (1999) concluded in a meta-analysis that daily and weekly supplementation are equally effective as far as people’s adherence to treatment is concerned. This highlights the important role of compliance during supplementation.

Efficacy studies have demonstrated that the impact of supplementation depends mainly on:

1. diet composition;

2. the presence of certain physiologic or pathologic conditions that could be influential for the absorption of iron (i.e., achlorhydria);

3. the composition of the supplement;

4. initial severity of iron deficiency;

5. time of intervention (Allen etal., 2006).

One randomized controlled study conducted in the United States with 513 low-income women pregnant for less than 20 weeks showed that women who received supplementation during the first trimester had a lower incidence of low birth weight and preterm birth. The conclusions from this study are clear: Iron supplementation administered prophylactically deserves to be examined as a measure for improving birth weight (Cogswell et al., 2003).

It should be noted that a considerable proportion of cases of anemia are not solely the consequence of iron deficiency. If the goal of public health programs is to keep anemia under control, the problem cannot be seen solely as iron deficiency. A randomized controlled trial of women from rural Nepal, supplemented with (a) folic acid, (b) folic acid plus iron, (c) folic acid plus iron plus zinc, and (d) folic acid plus iron plus zinc plus 11 other micronutrients and a control group treated with vitamin A showed greater hemoglobin concentrations in those who consumed the combination of folic acid plus iron.

Addition of iron absorption enhancers has yielded successful results in several studies. Recently, in Sweden an oats-based beverage to which citric acid and phytase were added to improve the absorption of supplemented iron found that citric acid improved the absorption of iron by 54% and phytase treatment by 78%.

The estimated cost of iron supplementation is US$3.17-$5.30 per child, which seems expensive, because of the long periods of treatment (daily or intermittently) required. This issue should be examined for cost-effectiveness. According to the reports of the Manoff Group (2001) and the Micronutrient Initiative (UNICEF, 2004), for each U.S. dollar invested in iron supplementation programs for pregnant women, there is a return of US$24 in lifelong salaries and prevention of disabilities. As for iron fortification of foods, for each U.S. dollar invested, the return is $84 in higher productivity and fewer disabilities.

Safety aspects. Iron toxicity is relatively uncommon, mainly because its intestinal absorption is tightly controlled. Iron intestinal absorption is downregulated when iron stores are replete or the dietary intake is excessive. Some populations suffering from a genetic alteration called hemochromatosis are at risk of iron poisoning during iron supplementation or food fortification interventions because the intestinal absorption of iron is two to three times the normal levels.

Toxicity caused by excessive consumption of iron tablets or syrup has been reported in children attending health services in the United States. An increase in morbidity has also been reported in small children with full stores of iron living in endemic malaria areas, as documented by the Pemba study. Iron and zinc compete for intestinal absorption, when administered in combination; one offsets the other’s absorption depending upon the molecular ratio. There are not large-scale programs in operation investigating this issue (Sazawal et al., 2006).

Date added: 2024-03-11; views: 579;