Crankshafts. Function in the Vehicle. Manufacturing and Properties

Function in the Vehicle. The internal combustion engine continues to be the prevalent power plant in motor vehicles, largely in the form of a reciprocating engine. This will continue to hold true in coming years. The development goal through 2008 is to reduce average C02 emissions from the current 190 g/km to 140 g/km, which corresponds to fuel consumption of about 5.7 liters per 100 km.

The Crankshaft in the Reciprocating Piston Engine. The piston’s linear movements are converted, with the intervention of the conrod, into rotational movement at the crank of the crankshaft, thus making torque available for use at the wheels.

Because of the strains involving forces that change in both time and location, with rotational and flexural torques and the resulting excitation for vibrations, the crankshaft is subject to very high, very complex loads.

Requirements. The crankshaft’s service life is influenced by

- Resistance to flexural loading (weak points at the transition from the bearing seat to the web)

- Resistance to alternating torsion (the oil bores are often weak points)

- Torsion alternation behavior (stiffness, noise)

- Wear resistance, at the main bearings, for example

- Wear at shaft seals (leaks, motor oil escaping)

For ecological reasons the trend is toward high-torque engines that will develop high moments even at low engine speeds. In these engines the crankshaft is subjected to far greater loading in all the respects mentioned above than is the case in conventional, aspirated engines.

Manufacturing and Properties. About 16 million crankshafts are required every year in Europe. The large majority (about 15.5 million) is used in passenger cars and light utility vehicles.

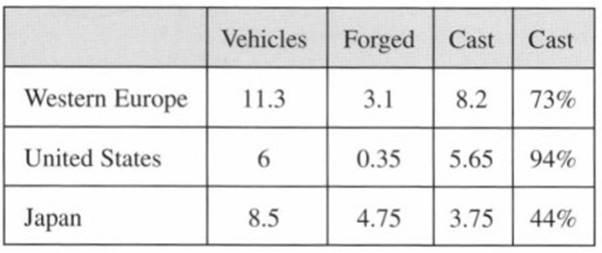

Processes and Materials. Crankshafts are either cast or forged. The shares accounted for by the individual manufacturing processes are shown in Fig. 7-102.

Fig. 7-102. Passenger car crankshafts, by manufacturing process (in millions of units, 1993)

The necessity for reducing C02 emissions (and fuel consumption) is leading increasingly to turbocharged gasoline engines, which at present are preferably fitted with forged crankshafts.

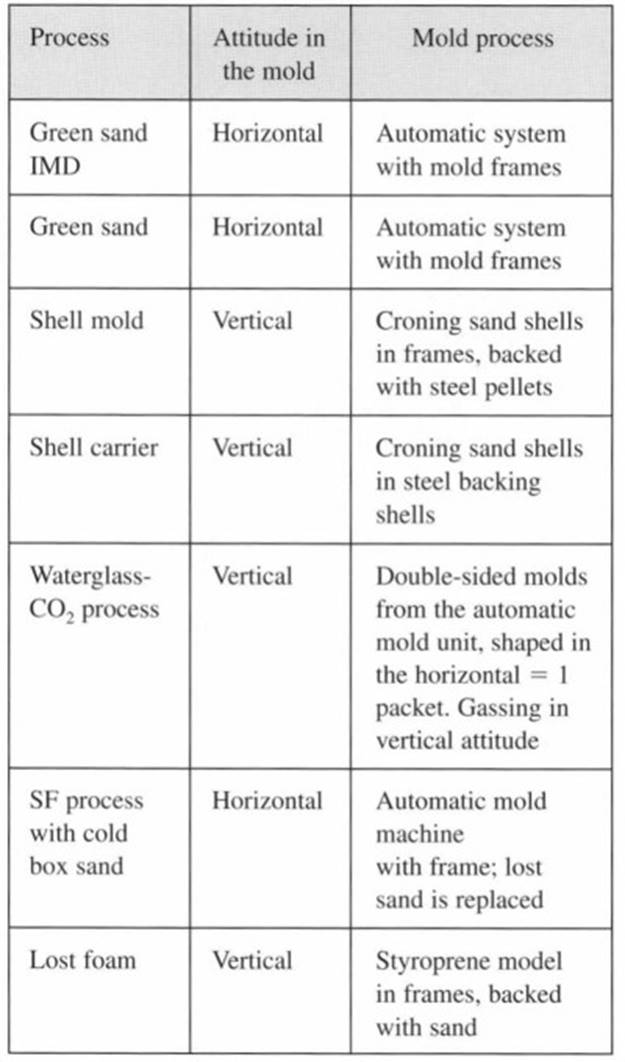

Casting. There are several processes available for casting crankshafts; they are listed in Fig. 7-103.

Fig. 7-103. Survey of casting processes used to manufacture crankshafts

Based on the evaluation of the various processes, we find that, due to better dimensional stability, there are advantages for the green sand IMD process. But the technique most commonly used in practice is the shell mold process.

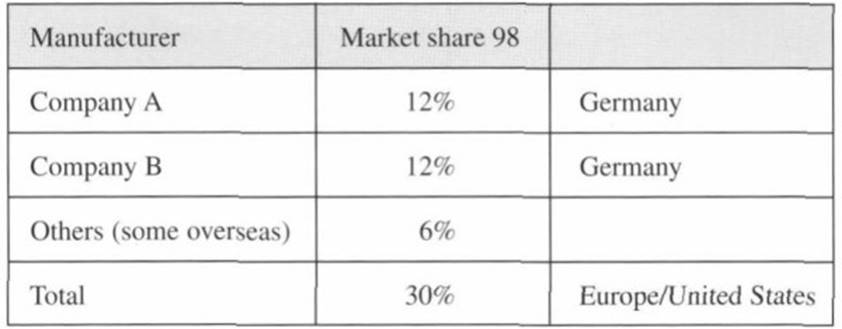

Forging. Two companies in Germany concentrate on making forged crankshafts for road vehicles; see Fig. 7-104. There were 13 such companies 30 years ago. Because of technological considerations, the trend toward forged crankshafts is continuing.

Fig. 7-104. Market shares held by manufacturers of forged crankshafts

Advantages and Disadvantages of Forged and Cast Crankshafts.

Advantages of Cast Crankshafts over Forged Crankshafts

- Cast crankshafts are considerably more economical than forged units.

- Casting materials respond well to surface finishing processes used to boost oscillation resistance. Thus, for example, the resistance to flexural loading can be increased considerably by rolling the radii at the transition between the journals.

- Cast crankshafts can be hollow and thus may be as much as 1.5 kg lighter in weight.

- Cast crankshafts of the same design offer a weight advantage of about 10% compared with steel, which is because of the lower density of the nodular cast iron.

- Machining the cast crankshaft is in general simpler. It is possible to work with smaller supplements for later machining, the mold parting flash is reduced and no longer needs be removed, and the slopes in the webs can be specified more closely. In fact, it is often possible to do without any machining of the webs at all.

Disadvantages of Cast Crankshafts Compared with Forged Crankshafts

- Casting materials have a lower Young’s modulus than steel. As a consequence, cast crankshafts are less stiff and exhibit different vibration properties.

- Measures implemented to increase drive train stiffness are even more necessary when aluminum blocks and crankcases are used, as this material has a far lower Young’s modulus and thus less material stiffness.

- Cast crankshafts, when compared with steel, may exhibit less favorable wear characteristics at the bearing journals, which is because of the microvoids in the surface (exposed spheroliths), lower fundamental hardness, and less enhancement of hardness in the usual hardening processes.

It is possible, however, to compensate for these advantages:

- By larger diameters in the bearing area, which is not possible for existing engine concepts and which is not desirable in new concepts because of greater friction losses and the associated rise in fuel consumption.

- With complex vibration dampers, which increase system costs, however, and can offset the cost advantage of cast crankshafts in comparison with forged versions.

- With a very stiff design for the engine block, joined with crankshaft bearing bridges, cast oil pans, and a stiff linkage with the transmission.

- With the ISAD (integrated starter alternator damper) system currently under development.

By eliminating the separate starter and alternator, this system offers the option of damping engine oscillations using “alternating reactive power.” Here any crankshaft overspeeding is braked by kicking in generator action and any lag is compensated by applying the energy stored in capacitors.

In torque-optimized engines the cast crankshafts have more physical problems with torsional oscillations, because of Young’s modulus and less stiffness, and this can lead to an unacceptable noise level in the vehicle. The Young’s modulus for steel is 210 kN/mm2 while that for GJS is 180 kN/mm2. Consequently, forged crankshafts are used at present in engines that develop high torques at low engine speeds. This applies, in particular, to engines with more than four cylinders as well as to diesel engines.

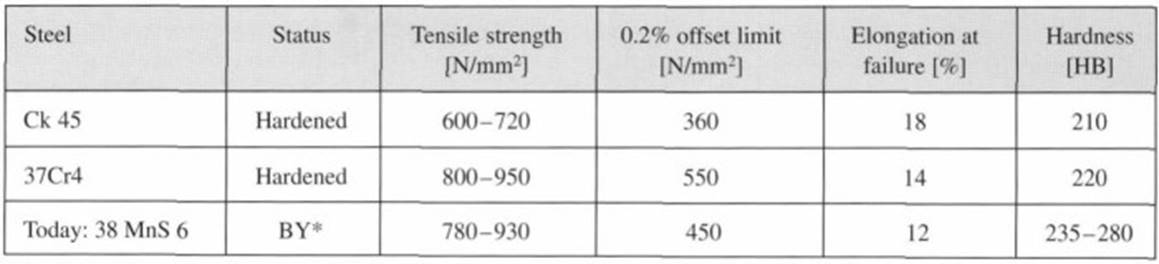

Fig. 7-105. Properties of forged crankshafts

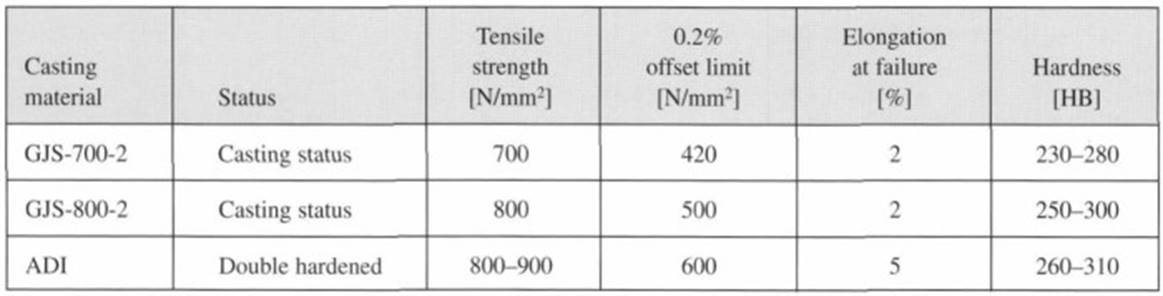

Fig. 7-106. Properties of nodular cast iron (GJS); minimum values

Materials Properties for Crankshafts. Crankshaft properties are shown in Figs. 7-105 and 7-106. GJS-700-2 is the material normally desired for crankshafts. The engine manufacturers sometimes have their own company specifications for spread of hardness values.

Date added: 2024-04-24; views: 654;