Domestic Heating. Typical "Wet" or Radiator Central Heating System

Most domestic space heating systems used in the twentieth century in Britain, continental Europe and the U.S. were developments of technologies introduced much earlier. At the beginning of the twentieth century, many homes, especially in Britain, were still heated by solid fuel open fires set in fireplaces with chimneys.

Closed solid fuel stoves of clay, brick or tile or metal stoves developed from the seventeenth century onward were also common methods of domestic space heating across continental northern Europe and North America, especially during the early parts of the twentieth century. Such coal- or wood-fueled stoves are typically four times more efficient than open fires. In addition to more efficient designs of metal stoves, new types of domestic room heater spread into use in the twentieth century as new fuels became available.

Gas heaters were invented in the 1850s; Pettit and Smith adapted Bunsen’s gas burner for domestic heating in 1856. Electric heaters became practical after the development in the early twentieth century (patented in 1906) of a nickel-chrome heating element that did not oxidize when heated. This American invention led to Ferranti’s parabolic reflector heaters in 1910 (in the U.K.) and Belling’s electric heater in 1912, in which nichrome elements wound on fireclay strips would heat the strips to incandescence.

Such units provided radiant heat, in which the heat travels in straight lines warming objects in its path. On the other hand, electric convector heaters, first introduced around 1910, provide warmth by convection through the movement of heated air. Fan-assisted electric convector heaters, first commercialized in the U.S. by Belling in 1936, only became popular after 1953 when a silent tangential fan heater was produced in Germany.

The storage heater is another type of electric convector heater also invented at the beginning of the twentieth century. A storage heater comprises a heat-conductive casing containing ceramic heat-retaining blocks that are gradually warmed by electric elements, usually overnight. The stored heat is then released, sometimes with fan assistance, the next day.

However storage heaters did not spread into use until after World War II. In Britain they were not much used until after 1962 when low-cost night electricity rates were introduced. Storage heaters provided a relative low-capital cost alternative to the central heating system.

The widespread use in Britain of individual room heaters into the late twentieth century was due to the much slower adoption of central heating than in most other developed countries. In 1970 only 30 percent of British homes had central heating, rising to 90 percent by the end of the century. In continental Europe and the U.S, where living in apartments and heating with closed stoves was more common than in Britain, domestic central heating spread much more rapidly.

Central heating is a system that heats a building via a fluid heated in central furnace or boiler and conveyed via pipes or ducts to all, or parts of, a building. There are many types of central heating system depending on the fuel used to heat the fluid—usually coal, oil, or gas (although wood fired and electric systems exist)—and the fluid itself, which may be steam, water, or air.

William Cook was the first to propose steam heating in 1745 in England. At first steam heating was mainly used to heat English mills and factories, but its development for domestic use took place mainly in America, notably by Stephen Gold who was granted a U.S. patent in 1854 for “improvement in warming houses by steam.’’

Many different designs of steam heating system were in use in America by World War I. Steam, however, never really became popular for domestic central heating due to its relative complexity and problems such as noise and fear of explosions. Steam piped under the streets from a central boiler was used instead for ‘‘district heating’’ of groups of residential and commercial buildings in large cities, especially in the U.S. New York’s famous steam district heating systems were introduced in the 1880s.

Many district heating systems were operated as ‘‘combined heat and power’’ (CHP) systems in which high-pressure steam was used first to drive electricity generating turbines and then distributed at low pressure, or as condensed hot water, to heat buildings. Utilizing the heat that otherwise would have been wasted increases the overall fuel efficiency from about 30% in a conventional power station to over 70% for a CHP system. District heating and CHP systems declined in the U.S. after the 1950s, and by the early twenty-first century, were most common in Russia and Scandinavian countries, especially Denmark.

Given the drawbacks of steam for ‘‘wet’’ domestic central heating systems, by the early twentieth century the preferred fluid became water. This is heated in a boiler and conveyed via pipes to radiators in individual rooms (really these should be called ’’convectors’’ as they heat a space mainly by convection rather than radiation). Warm air central heating systems were also popular in the U.S., Canada, and Germany.

In such systems air is heated via a furnace and distributed through sheet metal ducts to room vents. Initially hot water and air central heating relied on the density difference between the hot and cold fluid for circulation, so-called ‘‘gravity systems.’’ Subsequently electric pumps and fans were introduced to assist circulation, thus allowing smaller pipe work and more compact designs.

Whereas early systems could only be controlled by adjusting the rate of fuel burning, the introduction of central heating controls, starting with Honeywell’s clock thermostat in 1905, allowed more efficient and convenient utilization of heat.

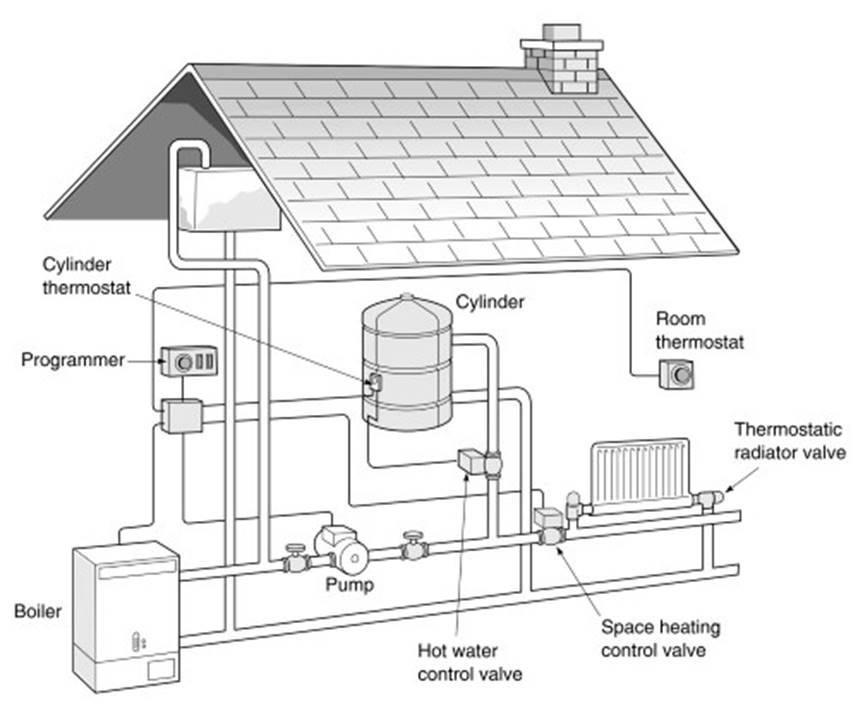

The fuel most commonly used by central heating furnaces and boilers also shifted from coal at the beginning of the twentieth century to oil and gas by the 1920s. By the 1930s most of the components of the modern domestic central heating system were in place, for example, the typical British thermostatically controlled, pumped radiator system heated by a gas boiler, which also provides hot water for bathing and so on (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Typical ‘‘wet’’ or radiator central heating system, showing location of main components and controls. [From: Roy, R. with Everett, B. The National Home Energy Rating Activity, Supplementary Material to Open University course T172 Working with our Environment, Milton Keynes: The Open University, 2000. [Fig A6, p 60] © 2000 The Open University.]

Following the oil price increases of the 1970s and growing concerns about the environmental impact of burning fossil fuels, attention has turned to the development and adoption of more fuel- efficient domestic heating systems that reduce the heat loss from buildings and utilize renewable energy. The first approach includes the installation of ‘‘condensing’’ central heating boilers in which the flue gases pass over a heat exchanger before exiting, thus increasing energy efficiency from approximately 65 percent to 90 percent.

Another example of fuel-conserving heating technology is the heat pump, which extracts heat from a low temperature source, such as the air or the ground, and boosts it to a temperature high enough to heat a room. Most heat pumps work on the principle of the vapor compression cycle. The main components in such a heat pump are a compressor (usually driven by an electric motor), an expansion valve, and two heat exchangers, the evaporator and condenser, through which circulates a volatile working fluid. In the evaporator, heat is exchanged from the air or from pipes in the ground to the liquid working fluid, which evaporates.

The compressor boosts the vapor to a higher pressure and temperature which then enters the condenser, where it condenses and gives off useful heat to the building. Finally, the working fluid is turned back into a liquid in the expansion valve and reenters the evaporator. Heat pumps were first demonstrated for domestic use in 1927 by Haldane in England and widely adopted in parts of the U.S. in the 1950s.

Solar energy for domestic heating, after experiments in the 1930s and 1940s, was given new impetus in the 1970s by the oil crisis and again in the 1990s by environmental concerns. Solar heating technology includes both ‘‘passive’’ and ‘‘active’’ systems. In passive systems, buildings are designed and oriented to maximize useful heat gain from the sun. In active solar thermal systems, the sun is used to heat a fluid (such as water) or air that can be used immediately or stored for space heating. Some solar homes provide space heating and hot water all year round without the need for any fossil fuel energy.

Date added: 2024-04-24; views: 640;