Inducible Local Defences

Notwithstanding the presence of preformed defences, the outcome of an interaction between a plant and a potential pathogen is largely determined by the presence or absence and the activities of specific molecules on the host and pathogen sides. The major components are (1) molecules characteristic of potential pathogens (traditionally termed elicitors) and (2) plant receptors that detect such molecules, as well as (3) pathogen effectors (see above), and (4) plant proteins, encoded by resistance genes, which recognise the presence or activity of these effectors.

A characteristic feature of the plant immune system is cell autonomy. Practically every plant cell is capable of mounting defence responses. Thus, many interactions remain highly localised; this is apparent, for instance, as tiny necrotic lesions on leaves, stemming from cell death.

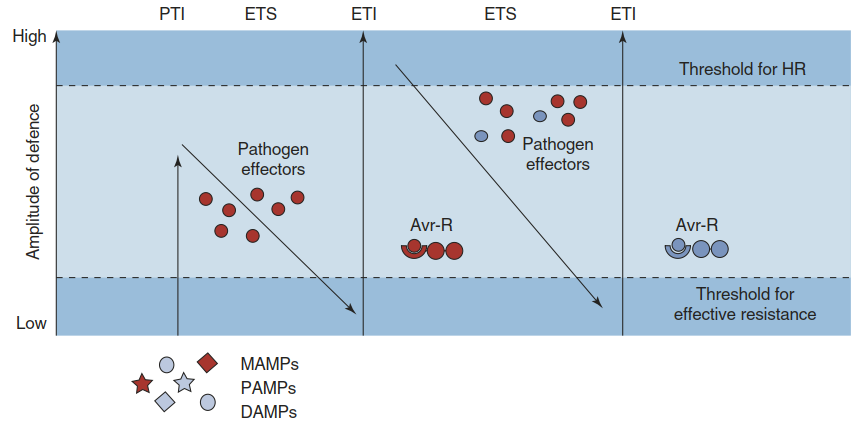

Depending on the severity of a pathogen attack, two principal amplitudes of defence based on two different recognition strategies can be distinguished. This is summarised in the zig-zag scheme of plant immunity (Jones and Dangl 2006) (Fig. 8.7), which provides a “unifying theory” integrating the multitude of plant defence responses and plant-pathogen interactions. The first layer fends off all potential foes that have not evolved specialised weapons to attack a particular plant. The respective pathogens are sometimes referred to as non-adapted pathogens, and the phenomenon is called nonhost resistance.

Fig. 8.7.Zig-zag scheme describing plant immunity. Two amplitudes of defence are activated by the recognition of two different types of molecules. The first line of defence depends on the perception of molecules typical of potential pathogens or their activities (microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)) and is sufficient to prevent colonisation in most cases. The second line of defence recognises effector molecules or the activity of effector molecules produced by specialised pathogens trying to overcome host defences. Activation triggers the hypersensitive response (HR). PTI PAMP-triggered immunity, ETS Effector-triggered susceptibility, ETI Effector-triggered immunity. For more details, see the text

The second, more intensive layer of defence becomes activated when a plant cell recognises an enemy equipped with effectors that could potentially overcome the plant’s defence. The responses are stronger and faster, and can eventually lead to the hypersensitive reaction—that is, localised cell death (scenario 4 in Fig. 8.5). Inability to respond to the effectors results in susceptibility (scenario 3 in Fig. 8.5).

In cases where preformed defences are not sufficient to completely prevent the activity of a potential pathogen, the first layer of inducible defence, the innate immunity, becomes active. Plant cells respond to the presence of a potential foe with the induction of various defence mechanisms. Antimicrobial compounds (phytoalexins) are synthesised, cell walls are locally reinforced and defence proteins such as enzymes (e.g. chitinases) to attack microbial cell walls are produced.

Plants do not only constitutively store a wide range of secondary metabolites that are disadvantageous for potential pathogens coming in contact with these molecules (see preformed defence and phytoanticipins, Fig. 8.6). In addition, the recognition of a potential threat triggers the de novo synthesis of compounds with antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of fungi, oomycetes and bacteria. Collectively they are termed phytoalexins (Greek alekein = “to fend off”) (Ahuja et al. 2012). The molecular mechanisms underlying their toxicity are largely unknown. Phytoalexins comprise a heterogeneous group of metabolites from different classes of secondary plant products.

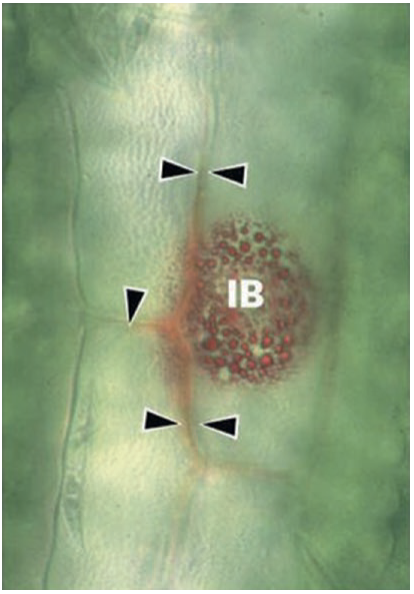

The predominant ones are isoprenoids, flavonoids and stilbenes. Examples include the stilbene resveratrol in grapevine and several isoflavonoids (e.g. medicarpin, pisatin) in legumes. Phytoalexin synthesis and exocytotic release are often highly localised at sites of pathogen attack. This is exemplified by vesicles filled with reddish defence compounds accumulating around a fungal penetration site on Sorghum leaves (Snyder and Nicholson 1990) (Fig. 8.8). Such localised response requires polarisation of the host cell, movement of particular organelles by the cytoskeleton and targeted secretion.

Fig. 8.8. A pathogen attack triggers highly localised defence responses. Phytoalexin accumulation (reddish inclusion bodies (IB)) and cell wall modification (arrows) are visible at an infection site on a Sorghum leaf

Likewise, cell walls are strengthened locally— for instance, right underneath an attempted penetration site of a biotrophic fungus (Fig. 8.4b). Small papillae are formed by deposition of callose (α β-1,3-glucan) and lignin. Cross-linking of extracellular proteins with the cell wall matrix further reinforces the mechanical barrier to fungal ingress.

A third element of the defence response is the synthesis of many pathogenesis-related proteins (PR proteins) which, contrary to what the name suggests, are in fact proteins thought to have antimicrobial activity. As for a range of other stress-related proteins in plants, their actual biochemical function is poorly understood. Exceptions are chitinases and glucanases, which attack fungal cells walls.

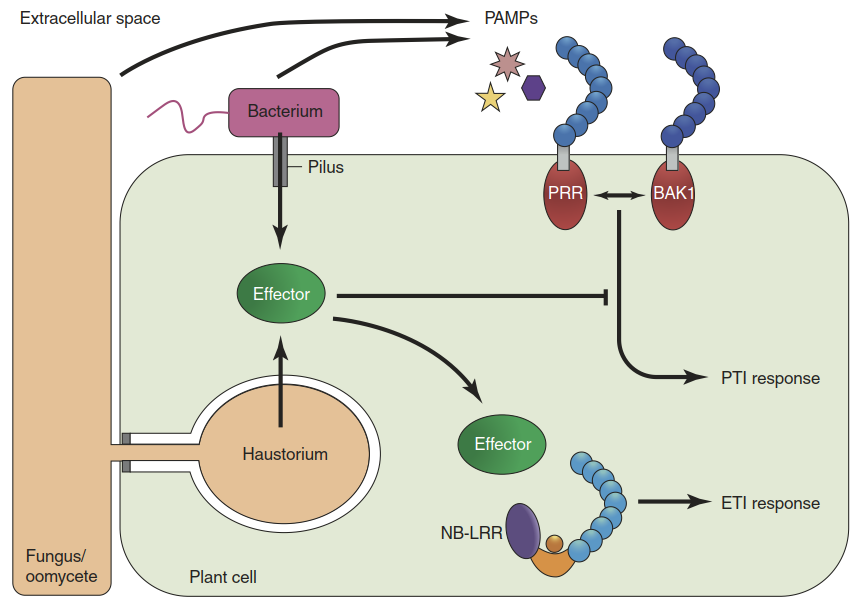

Defence responses are dependent on changes in gene activity. Genes encoding PR proteins or enzymes involved in phytoalexin biosynthesis and in the deposition of callose are induced. The responses are mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) residing in the plasma membrane of plant cells (Fig. 8.9). PRRs bind pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or, more generally, microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). PAMPs/MAMPs correspond to elicitors in the older literature. Defence responses elicited by PAMPs/MAMPs result in PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) (Figs. 8.7 and 8.9).

Fig. 8.9. Pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI). Perception of PAMPs (or microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)) by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their co-receptors (e.g. BAK1) triggers PTI responses. Specialised bacterial, fungal or oomycete pathogens release effector molecules to suppress PTI responses. Effectors or their activities are recognised by resistance gene products, typically nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat domain (NB-LRR) proteins. This event triggers ETI responses such as programmed cell death. For the sake of clarity, the plant cell wall is not shown

PAMPs/ MAMPs represent molecules that are highly conserved in microbial species but absent from plants. A classic example is flagellin, the major protein of bacterial flagella. Receptor-mediated perception of flg22, a 22-amino acid peptide that is part of flagellin, reliably indicates the presence of flagellated bacteria. Similarly, chitin fragments give away fungal cells in the vicinity because chitin is a major polymer of the fungal cell wall and PRRs recognising chitin fragments are known. A third group of molecules perceived by PRRs are so-called danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These are characteristic structures not of microbes but, rather, of microbial activity. Examples are pectin fragments released by cell wall-degrading polygalacturonases of necrotrophic fungi (Boller and Felix 2009).

The number of PRRs per plant species is estimated at around 100-200. Together they constitute an effective surveillance system that enables plant cells to sense the extracellular presence of many different potential microbial pathogens. The innate immunity based on this surveillance system is mechanistically very similar to animal innate immunity. However, plant cells express far more PRRs than animal cells. This is regarded as one way to compensate for the absence of an adaptive immune system in plants (Dodds and Rathjen 2010).

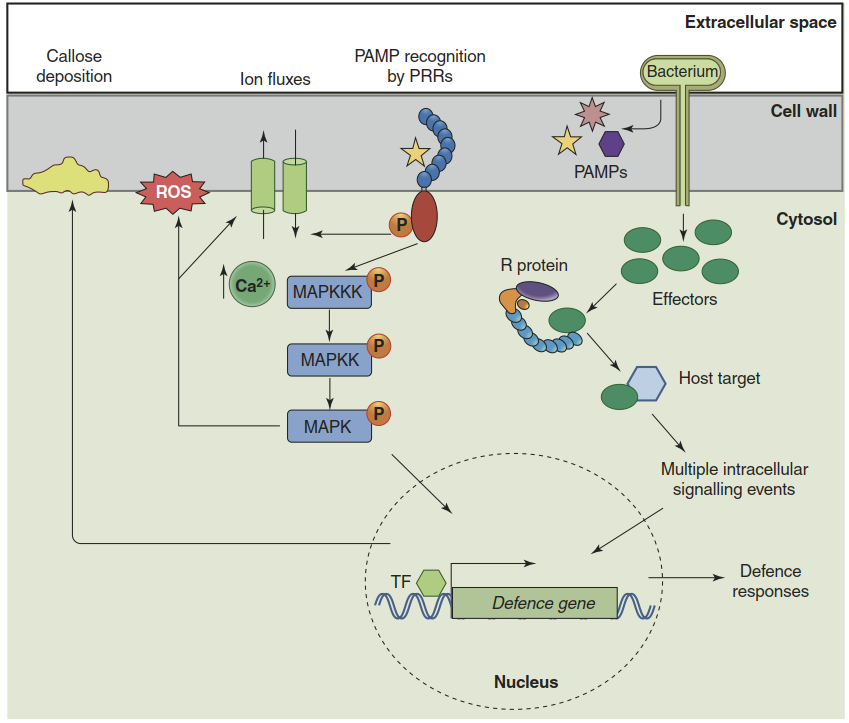

Activation of PRRs triggers signal transduction events that (1) result in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by plasma membrane-localised reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (NADPH oxidases) and extracellular peroxidases, causing an oxidative burst; and (2) result in altered gene regulation (Fig. 8.10). The oxidative burst has at least three different functions. ROS production in the apoplast supports local strengthening of the cell wall. H2O2 can be used as a substrate to cross-link molecules of the cell wall matrix. ROS can also directly damage pathogens. Finally, ROS may serve as signalling molecules and modulate the host cell response.

Fig. 8.10. Signal transduction in pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI). PAMP recognition triggers mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphorylation cascades, Ca2+ spikes, modulation of ion fluxes (plasma membrane depolarisation) and an oxidative burst (reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation). Defence genes are activated and the cell wall is reinforced by callose deposition. Signalling downstream from effector recognition (shown on the right side in the scheme) is poorly understood

Transduction of the signal from activated PRRs to ROS-producing enzymes and to transcription factors proceeds via multiple phosphorylation steps. PRRs themselves are receptor kinases. Upon ligand binding they interact with co-receptors and become activated (Fig. 8.10). Ca2+ spikes and the activation of mitogen- activated protein kinase cascades (MAP kinase cascades) eventually modulate a complex network of transcriptional regulators that ensures an adequate response—that is, a reprogramming of the cellular metabolism, which is adjusted to the severity of the pathogen threat (Tsuda and Somssich 2015). Like all plant stress responses, PTI represents a balancing act to optimise resource allocation between defence and growth.

The second layer of defence is activated when pathogen effectors are recognised. At this level of immunity most of the co-evolutionary dynamics take place because unlike MAMPs/PAMPs/ DAMPs, effectors are highly variable and also dispensable—that is, not essential for normal cell functioning (Dodds and Rathjen 2010). Therefore, effector recognition requires large sets of resistance genes (R genes), which are plant species specific and even genotype specific, while many PRRs are conserved across plant families because they perceive PAMPs, which are widely conserved as well. R gene products mediate the effector perception and the resulting effector-triggered immunity (ETI; see zig-zag scheme in Fig. 8.7).

As described in Sect. 8.1.2, during infection, plant pathogens synthesise and release up to several hundred effector molecules, which target a variety of sites in a host cell. Successful manipulation of the host defence system by well-documented examples such as avrBs3 (Fig. 8.2) and chorismate mutase results in effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS; see zig-zag scheme Fig. 8.7). A comparison across many different plant pathogen systems, which is now possible because of genome-wide studies, reveals that in spite of the huge diversity of effector molecules produced by bacteria, fungi, oomycetes or nematodes, the number of host processes that are predominantly targeted is rather small (Mukhtar et al. 2011; Dou and Zhou 2012).

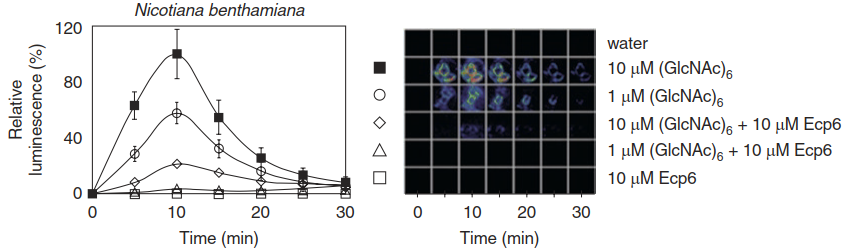

The list provides deep biological insight into key processes of defence and pathogenicity. It includes PRR-dependent immune responses, hormonal regulation, secretory processes and cell death programmes. Interference with PTI, for instance, is achieved either by effector proteins that inactivate PRRs directly or by proteins that reduce the concentration of DAMPs. The Pseudomonas syringae effector avrPto, for example, directly interacts with the flagellin receptor and other PPRs (Xiang et al. 2008). The Cladosporium fulvum effector Ecp6 binds chitin fragments in the apoplast and thereby inhibits activation of the respective PRRs sensing these DAMPs (de Jonge et al. 2010) (Fig. 8.11).

Fig. 8.11.Activity of a fungal effector. The fungal effector Ecp6 is produced by the fungal plant pathogen Cladosporium fulvum. It suppresses the recognition of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) by binding to chitin fragments. An oxidative burst of Nicotiana benthamiana cells, visualised as the chemiluminescence of oxidised luminol, upon treatment with fragments of chitin (GlcNAc)6 is shown

Upon recognition of an effector, a plant cell mounts a strong and rapid response that confers ETI. The most extreme manifestation of this response is the hypersensitive reaction, meaning programmed cell death, which effectively blocks further spread of an invading pathogen.

ETI is dependent on R genes. R genes can confer resistance to fungi, oomycetes, bacteria, nematodes and even viruses. They have been used extensively in crop breeding to achieve resistance against commercially important pathogens. Their molecular nature, however, was not known until 1995. Most R genes encode proteins that share certain structural domains— namely, leucine-rich repeats (LRRs), often involved in intermolecular interactions—and nucleotide-binding (NB) domains. There are, however, intriguing exceptions. The R gene Bs3 in pepper “outsmarts” pathogens carrying the effector avrBs3 (Fig. 8.2). When activated, Bs3 triggers a hypersensitive reaction (Romer et al. 2007). Bs3 is activated by avrBs3 binding because the Bs3 promoter carries the same cis element that is targeted by avrBs3 to cause disease. In other words, by attacking a plant cell with Bs3 in its genome, Xanthomonas campestris terminates its own infection attempt.

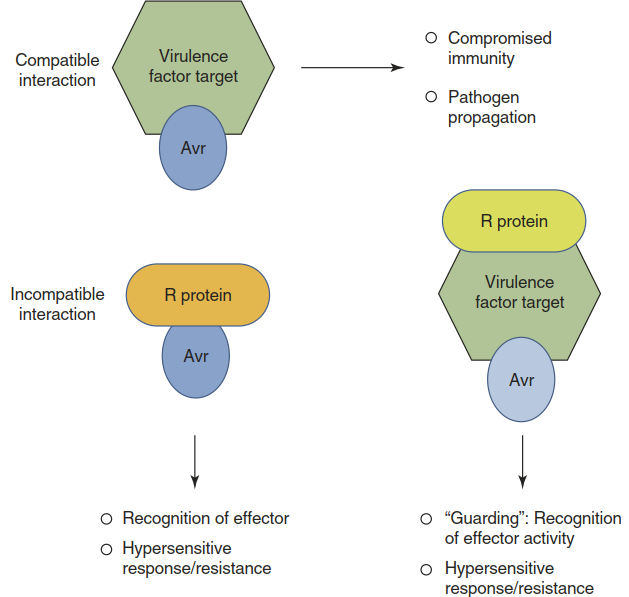

R gene products have two principal functions: recognition of pathogen effectors and triggering of a cell death programme upon activation (Figs. 8.7, 8.9 and 8.10). The gene-for-gene interaction between pathogen effectors and host R genes raises the question: How do plants keep up with pathogens in the evolutionary race? Microbial pathogens can evolve new effectors much faster than plants can evolve R genes. Their mutation rate is higher and their generation time much shorter. In fact, in an agricultural context, resistance is often broken by the emergence of new pathogen races. The adaptive immune system of animals generates a seemingly unlimited number of immune receptors and antibodies to cope with the genetic diversity and rapid evolution of pathogens. Part of the answer for plants lies in the way R gene products recognise effectors. Not all of them directly interact with effectors.

As postulated by the “guard hypothesis” (Jones and Dangl 2006), many R gene products guard critical virulence targets and recognise not the effector itself but the abnormal modification of a host protein caused by an effector (Fig. 8.12). In this way a particular R gene can sense several different effectors, in some cases even from pathogens as diverse as fungi and nematodes. Structurally unrelated effectors of the fungal pathogen C. fulvum and the plant- parasitic nematode Globodera rostochiensis both perturb the function of an extracellular protease (Rcr3) that is important for resistance of tomato cells. The R gene Cf2 encodes an immune receptor that guards Rcr3—that is, it senses changes in Rcr3 and confers resistance against genotypes of the fungus and the nematode that express the respective effectors (Lozano-Torres et al. 2012).

Fig. 8.12. The “guard hypothesis”. Resistance proteins (R proteins) recognise either effectors (encoded by avr genes) or the modification of critical virulence targets by effectors. Both scenarios trigger a hypersensitive response and confer resistance; the interaction is incompatible. Successful attack on a virulence target compromises immunity and contributes to pathogen propagation (compatible interaction)

Another reason why plants are not overwhelmed in the “arms race” with microbial pathogens is the diversity of R genes, which is driven by the continuous emergence of pathogen effectors. Plant genomes carry large numbers of R genes, many of them organised in clusters facilitating recombination events. R genes are consistently the most polymorphic class of genes in plant genomes. Thus, within a given plant population, hundreds or thousands of R gene variants exist that can sense effector-dependent pathogen attacks. Genetic diversity within a population reduces the vulnerability to pathogens.

The second function of R gene products, besides direct or indirect recognition of pathogen effectors (i.e. signalling to activate cell death programmes (Figs. 8.9 and 8.10)), is molecularly poorly understood.

Date added: 2025-02-01; views: 374;