Preformed Defences Against Bacteria, Fungi and Oomycetes

Features of a plant’s morphology and anatomy serve as a first line of defence against invasion by pathogens. The cuticle and cell walls form mechanical barriers against pathogen ingress. Many potential pathogens never gain access to plant cells and their resources, because they lack the means to overcome these barriers.

A characteristic of plant biology is the synthesis of thousands of secondary metabolites—that is, compounds that, in contrast to primary metabolites, are not found in every plant cell and species. Instead, different plants produce different spectra of secondary metabolites, which nonetheless serve important functions in the interaction of a plant with its environment (Bednarek and Osbourn 2009). Because “secondary” might be misunderstood as meaning “of lesser importance”, “specialised metabolites” was proposed as an alternative and perhaps more meaningful term (Pichersky et al. 2006). Nonetheless, throughout this chapter the more common term “secondary metabolites” is used.

Another sensible distinction between primary and secondary metabolites is this: primary metabolites are involved in nutrition and essential metabolic processes; secondary metabolites are involved in the interaction of a plant with its environment (Buchanan et al. 2015). A prominent role is preformed chemical defence against pathogens. Plants produce a rich cocktail of compounds with antimicrobial activity, which are mostly stored in vacuoles or in specialised cells such as trichomes. Sometimes they are referred to as phytoanticipins (Fig. 8.6) and are distinguished from phytoalexins, which are synthesised de novo upon pathogen attack.

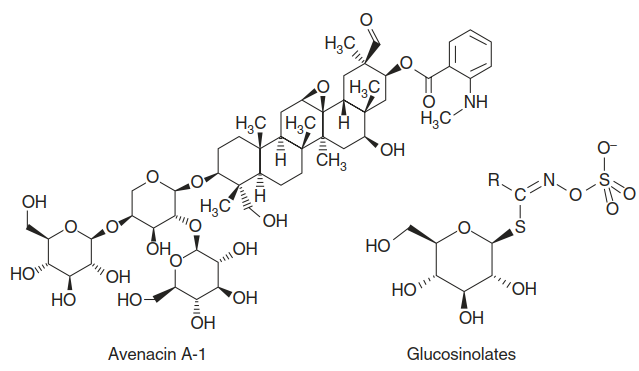

Fig. 8.6. Phytoanticipins. Saponins such as avenacin A-1 are found in Avena sativa but also in a wide range of other plant species. Glucosinolates are typical of Brassicaceae and other families in the Capparales

Biotic interactions are regarded as an important driver of the evolution of an extremely rich diversity of secondary metabolites (Dixon 2001), a resource that provides important services to humans as a major source of pharmaceuticals. However, the spectrum of secondary metabolites produced by a given plant species is far from completely known even in the model systems. Also, because most compounds act as ingredients in a complex cocktail, few examples of a directly demonstrated antimicrobial effect exist. Saponins are widely distributed amphipathic triterpenoid or steroid glucosides with soap-like behaviour in aqueous solutions. One example is avenacin, found in oats (Fig. 8.6).

Saponins provide broad-range protection against microbial pathogens. Mutant oat genotypes lacking saponin synthesis in root epidermal cells become susceptible to Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, a pathogen that usually cannot infect oat but is able to colonise wheat and barley—two species that do not synthesise saponins. Conversely, successful pathogens have evolved the ability to metabolise saponins. The main tomato saponin, α-tomatine, is metabolised by the tomato pathogen Septoria lycoper- sici via secretion of a tomatinase. This enzyme is crucial for the pathogenicity of S. lycopersici (Bouarab et al. 2002). Another well-studied example of preformed chemical defence is the synthesis of glucosinolates (Fig. 8.6), which will be described in more detail as part of a plant’s herbivory defence.

A rare alternative to chemical defence is so-called elemental defence. Metal hyperaccumulating plants apparently fend off pathogens and herbivores by accumulating metals such as Zn or Cd to toxic levels in their leaves.

Date added: 2025-02-01; views: 352;