Soil Structure and Pore Space: The Foundation of Soil Health and Function

Soil structure is fundamentally defined as the shape, size, and spatial arrangement of individual soil particles and their clusters, known as aggregates. An alternative, and increasingly relevant, definition describes it as the combination of solid particles with the different types of pores between them. While traditionally measured by aggregate characteristics, research confirms that the size, shape, and arrangement of the pore space itself most directly influence critical processes like plant root development, water storage and movement, gas diffusion, and solute transport. It is this pore architecture that provides the physical habitat for the entire soil biota, making its measurement essential for characterizing true soil quality.

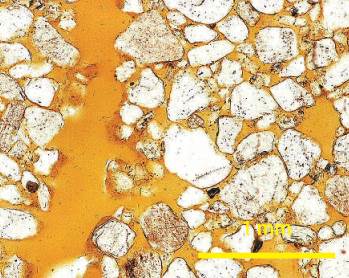

The quality of soil structure is profoundly dependent on the soil's organic matter content. Micromorphological techniques, which involve the microscopic examination of soil thin sections, provide valuable insights into this relationship. For instance, Fig. 2.6 shows organic matter accumulated as coatings along the walls of elongated pores. These coatings act as a natural cement, sealing and stabilizing the pores against the destructive impact of water and ensuring their long-term functionality, which is vital for water infiltration and root growth.

Fig. 2.6: Macrophotograph of a vertically-oriented thin section. Organic materials can be seen clearly as coatings on pore walls. Pores appear yellow

However, these favorable structural conditions are not permanent. When organic matter is fully decomposed and mineralized by soil microbes, it loses its cementing properties. This degradation leads to the collapse of pore walls and the eventual closing of the pores, representing the first critical step in soil structure degradation. This cycle highlights the indispensable role of fresh, continuous organic matter inputs in maintaining a healthy and stable soil pore system.

The intricate link between physical structure and biological activity is demonstrated by correlations between soil porosity and biochemical properties. Studies have found a clear correlation between soil enzyme activity and pores with diameters of 30 to 200 μm. This implies that larger pore spaces support more intense biochemical reactions, likely because they can house greater numbers and diversity of microorganisms. This positive relationship is consistently observed in soils amended with compost, underscoring the dual benefit of organic inputs in enhancing both structure and biology.

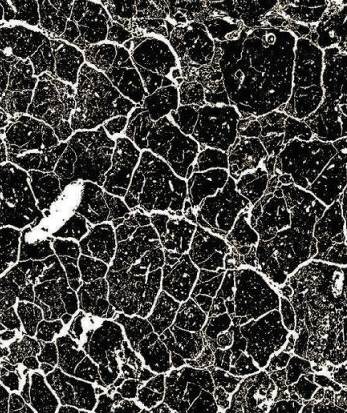

An exemplary model of good soil structure is shown in Fig. 2.7, which illustrates a subangular blocky structure. Here, soil aggregates are separated by interconnected, elongated pores. From an agronomic perspective, this is considered the optimal structure because the continuity of these pores facilitates excellent water movement and provides easy pathways for root penetration. Furthermore, this structure is inherently stable, allowing for the characterization and prediction of fluid transport processes within the soil profile.

Fig. 2.7: Macrophotograph of a vertically oriented thin section showing an example of subangular blocky structure. The white areas represent the pores. Frame length 35 cm.

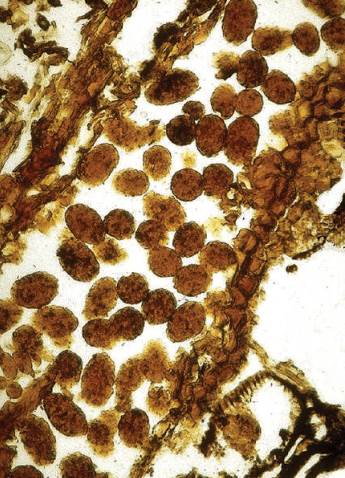

The visual evidence of biological activity shaping soil structure is clearly represented in Fig. 2.8, which shows accumulations of organic materials within pore spaces. A more detailed examination in Fig. 2.9 reveals that this material includes faecal pellets from small insects and mites, demonstrating how soil fauna contribute to organic matter distribution and micro-aggregate formation. Figure 2.10 provides a macro-scale example, showing a distinct channel and chamber formed by the activity of earthworms, classic ecosystem engineers.

Fig. 2.8: Macrophotograph of a vertically oriented thin section. The white areas represent the pores. In the pore spaces fragments of root remains and small organic materials can be seen. Frame length 32 cm.

Fig. 2.9: Microphotograph showing faecal pellets of small insects and mites. The white areas represent the pores. Frame length 33 mm

Fig. 2.10: Microphotograph of vertically oriented thin section showing a channel and chamber formed by soil fauna

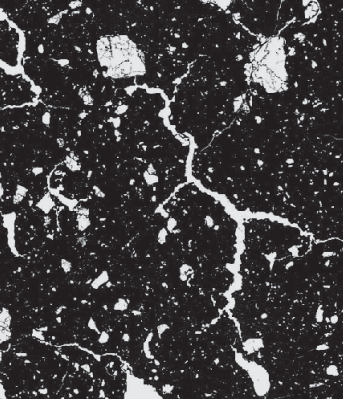

In stark contrast, Fig. 2.11 represents a compacted soil with very poor structure. There are no visible, separated aggregates, and porosity is extremely low, consisting only of small, isolated pores within a dense soil matrix. This type of structure creates an unfavorable habitat for both plant roots and the soil biota, and it is a common feature of degraded soils suffering from low organic matter content, leading to impeded drainage and aeration.

Fig. 2.11: Macrophotograph of a vertically oriented thin section showing an example of massive structure as evidenced by the relative lack of pore space and pore connectivity. The white areas represent the pores. Frame length 35 cm

The impact of soil life on structure is observable at the field scale, particularly the work of macrofauna like earthworms. The potential of earthworms to improve soil aggregation and porosity was famously documented by Gilbert White in 1777 and Charles Darwin in 1837. They recognized that earthworms promote plant growth by creating an intimate mixture of organic and mineral matter, which enhances water retention, nutrient release, and provides a superior medium for root proliferation.

The soil pore space is systematically categorized based on size and function, with each type directly affecting soil properties:

- Macropores (>50 μm): These are the largest pores, often formed by soil cracking, root growth, or burrowing animals. They are critical for the rapid drainage of water and the exchange of gases within the soil, preventing waterlogging.

- Mesopores (2 - 50 μm): These pores are essential for water storage and are the primary source of moisture available for plant uptake. When soil is at field capacity after rainfall, it is the mesopores that are full of water.

- Micropores (<2 μm): Water in these tiny pores is held so tightly by adhesive forces that it is generally unavailable to plants. However, these moist, often anaerobic conditions are beneficial for specific groups of microbes, such as those involved in denitrification.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 102;