Soil Structure and Porosity: The Hidden Architecture of a Dynamic Habitat

To a surface observer, soil may appear as a static, uniform mass. In reality, it is an incredibly dynamic and heterogeneous system, teeming with life and complexity. This vibrant environment consists of a intricate network of pore spaces filled with air and water, hosting a vast community of organisms of all shapes and sizes. These pathways form an immensely complicated structure, extending meters downward through routes that can be either relatively direct or incredibly tortuous, creating a three-dimensional world beneath our feet.

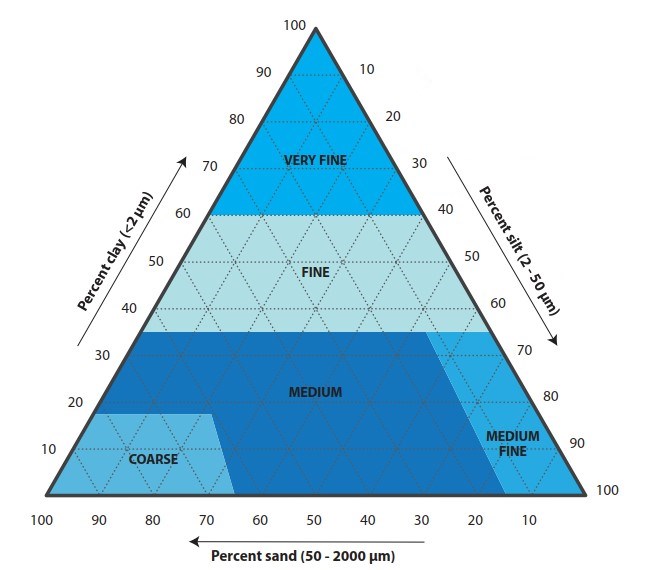

The physical character of soil is defined by its texture and structure. Soil texture is determined by the differing proportions of the mineral components—sand, silt, and clay—allowing for classification on a spectrum from coarse to very fine (Fig. 2.1). Soil structure, however, refers to the combination and arrangement of these primary particles into larger secondary units known as aggregates or peds. These aggregates exhibit various shapes, such as 'subangular blocky,' 'prismatic,' or 'granular,' which fundamentally influence the soil's behavior.

Fig. 2.1: Soil textural triangle used for defining soils by texture

The specific combination of soil structure and texture governs critical ecosystem functions. Soils interact differently with water, affecting processes like drainage, capillary rise, and swelling. They also vary in their capacity to bind and release nutrients, determining the availability of essential elements to plants. From a biological perspective, the most critical aspect is the pore structure, as this network provides the essential habitat for plant roots and the entire soil food web, dictating where life can exist and thrive.

The living space within soil, particularly for microorganisms, is immense. Pore space can constitute almost 50% of the total soil volume, although a significant portion consists of micropores too small for many organisms to enter. Research has demonstrated that the internal surface area within a single gram of clay soil can exceed 24,000 m², a value that decreases with higher proportions of silt and sand. This colossal surface area, even with its microscopic constraints, explains why a small amount of soil can support such a staggering array and abundance of life, functioning as a metropolis for microorganisms.

Soil is fundamentally a semi-aquatic habitat, with the majority of its organisms, especially microorganisms, requiring water for survival and mobility. When a soil is saturated, all its pores are filled with water. After free drainage ceases, the soil reaches field capacity, a state characterized by the specific suction pressure needed to remove water. As drying continues, increasingly greater pressure is required to extract moisture, with larger pores draining first due to weaker water-holding forces.

The dynamics of water retention are scale-dependent. Medium-sized pores drain next, while micropores are the last to lose water due to powerful electrostatic forces between water molecules and soil particles. Eventually, the only remaining water is bound so tightly in these tiny spaces that plants cannot extract it. This critical threshold is known as the permanent wilting point, defined by a suction pressure exceeding -15 bar, beyond which plants wilt as the moisture becomes physically inaccessible.

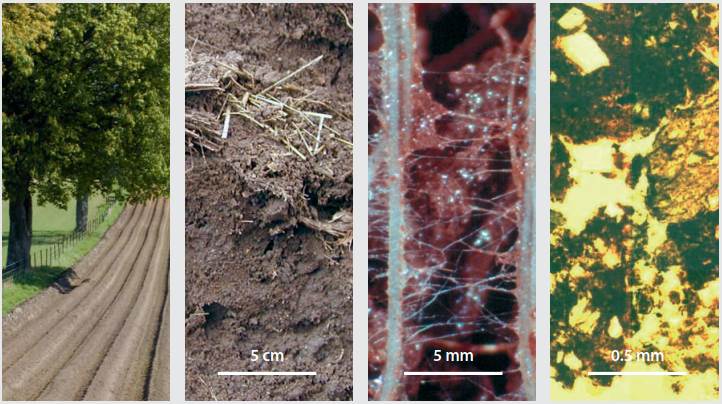

The scales at which life exists within soil are unfamiliar to most humans. We typically perceive soil as a two-dimensional planar surface. However, upon digging, one encounters the next scale, where soil aggregates and organic matter mixtures become visible, revealing the first clear signs of the soil's structural complexity and the beginnings of its three-dimensional pore structure.

Increasing the magnification further reveals a world where plant root hairs and symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi become apparent. At this scale, the significant amount of space available for microbial life and root exploration starts to become tangible. This highlights the intricate architecture that supports biological activity and nutrient exchange, forming the basis of the soil ecosystem's productivity.

The fourth image provides a view of a soil thin section, where soil is embedded in resin and sliced for microscopic examination. When backlit, the pore spaces between the soil aggregates are clearly illuminated (often shown in yellow). This technique visually confirms that a substantial portion of soil is not solid matter, but space that can be filled with either air or water, depending on the prevailing moisture conditions.

The proportion of pore space to solid particles is a critical property influenced by several factors, with soil texture being primary. For example, a fine-textured clay soil can have a pore space constituting almost half of its total volume. In contrast, a medium-textured loam may have a porosity closer to 40%. This variation in space directly controls habitat availability, water storage, and gas exchange, making it a foundational element of soil health and function.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 129;