The Rhizosphere: A Dynamic Interface for Soil-Plant-Microbe Interactions

The term rhizosphere was formally introduced in 1904 by the German soil microbiologist Lorenz Hiltner, who defined it as the soil volume influenced by living plant roots. This influence creates distinct physicochemical and biological gradients that diminish with increasing distance from the root surface, differentiating the rhizosphere from the surrounding bulk soil. Characterized by low carbon availability and slow nutrient diffusion, the bulk soil is a relatively poor environment with reduced biological activity. In stark contrast, the rhizosphere is a hotspot of nutrient availability and intense biological activity, primarily driven by the process of rhizodeposition.

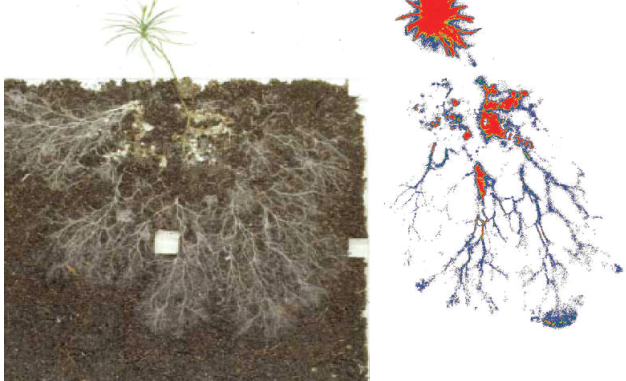

The spatial extent of the rhizosphere is variable, directly affected by soil texture, plant species, and moisture content. Direct root effects typically operate within a range of a few micrometers up to approximately 7 mm from an active root segment. However, these effects can extend several centimeters, especially for highly mobile compounds like water or CO₂. This range is significantly amplified by fungal hyphae from mycorrhizal root segments, creating a distinct zone of influence known as the mycorrhizosphere (Fig. 2.20). The inner boundary of the rhizosphere is not precisely defined, and some models wisely include the root as a whole, acknowledging the movement of substances and endophytic microorganisms within root tissues.

Fig. 2.20: Scan of a microcosm containing a mycorrhizal pine seedling labelled with 14CO2 (14C is a radioactive form of carbon). The image on the right shows where the carbon has been fixed by the plant through photosynthesis and transported down into the roots. The transport of the carbon, in the form of sugars containing 14C into the mycorrhizosphere is clearly visible (from Finlay 2006). Images reproduced with permission from New Phyologist

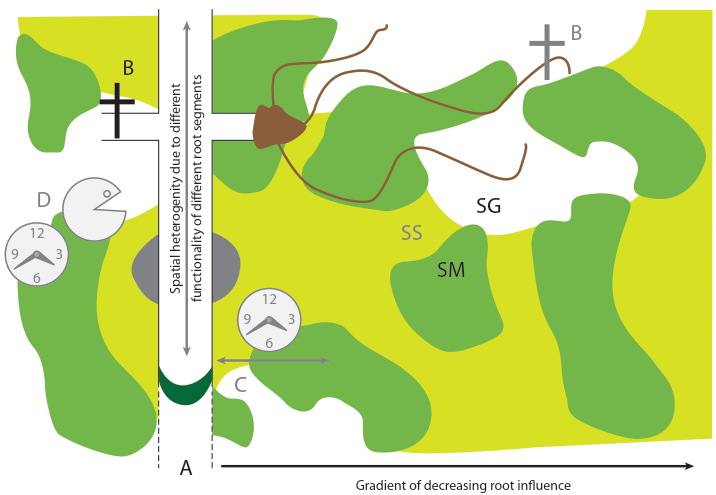

Key Processes Governing the Rhizosphere Environment.Soil is a complex, heterogeneous three-phase system, as illustrated in Fig. 2.21, where plant roots are major drivers of spatial and temporal change. The two most critical processes altering soil properties near roots are water and nutrient uptake, and the release of organic carbon compounds. Plant water uptake establishes soil moisture gradients, while nutrient absorption creates chemical gradients within both the solid and solution phases of the soil. These activities collectively shape the unique environment of the rhizosphere.

Fig. 2.21: A schematic representation of the rhizosphere as a 3-phase system with soil solid matter phase (SM), soil solution phase (SS), and soil gas phase (SG). Spatial heterogeneity along and perpendicular to root growth added by a developing root system is emphasised and is overlaid by temporal variability: (A) root growth, (B) turnover of roots and fungal hyphae, (C) diurnal or seasonal changes in the activity of roots (i.e. exudation, uptake), or (D) associated organisms. From Luster et al. 2009

Perhaps the most influential process is the root release of photosynthetically fixed carbon, a mechanism plants can actively induce. This rhizodeposition serves various functions, including enhancing nutrient solubility, detoxifying harmful elements like aluminum, and managing microbial populations by attracting beneficial organisms or deterring pathogens. For instance, plants can exude low-molecular-weight organic acid anions to solubilize phosphorus or chelate toxic metal ions, thereby improving their growth conditions (Fig. 2.22). This strategic release of carbon is a cornerstone of plant-soil feedback.

Fig. 2.22: The main photograph shows the roots of trees and herbaceous plants exposed in a cutting within a sandy soil in Hungary. Soil texture and structure are important controls on the development of roots. (EM); The inset shows root exudates binding with aluminium ions in the rhizosphere of Lupinus luteus, thereby reducing their toxicity, as visualised as bleaching of the red Al-aluminon complex. (from Neumann 2006)

Root growth itself contributes significantly to rhizodeposition through the sloughing-off of living cells, senescence, and cell wounding. This passive release adds a diverse suite of components to the soil. Furthermore, roots and mycorrhizal fungi release gases, with carbon dioxide being a common byproduct and oxygen release being a crucial adaptation for wetland plants to create a well-aerated root environment. The collective sum of all root-released materials accumulating in the soil is comprehensively termed rhizodeposition.

Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity and Biological Interactions.Rhizosphere properties are not uniform, exhibiting both radial gradients from the root and longitudinal heterogeneity along the root's axis (Fig. 2.21). Different root segments have specialized functions; for example, the root tip (apical zone) and root hairs are known hot spots for intense nutrient uptake and rhizodeposition. Additionally, root influence varies temporally due to daily cycles, seasonal changes, and the plant's developmental stage, though these dynamic effects are still not fully documented. This complexity makes the rhizosphere a highly dynamic and variable microhabitat.

Following root death, the legacy of the rhizosphere persists. Deceased root segments first act as localized organic matter sources and, after decomposition, leave behind macropores that profoundly impact soil transport properties for water and air. Combined, ongoing rhizodeposition and root turnover can contribute up to 40% of the total carbon input into soils. This substantial carbon input is a critical component of the global carbon cycle.

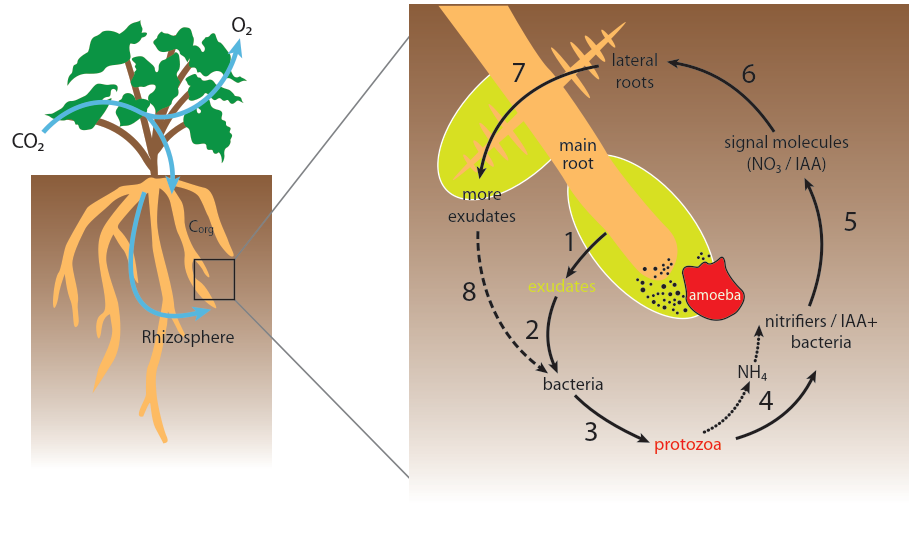

The high availability of easily degradable carbon from rhizodeposition fuels immense microbial activity, which can be up to 50 times greater in the rhizosphere than in the bulk soil. This forms the foundation of a complex soil food web, interlinking bacteria, fungi, nematodes, protozoa, and microarthropods. This community comprises neutral organisms, deleterious pathogens, and beneficial mutualists like nitrogen-fixing bacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). The microbiota actively reshapes the rhizosphere environment by degrading and secreting organic compounds and through the lysis of plant cells.

Fig. 2.23: A conceptual model of feedback loops within a rhizosphere involving different members of the soil food web. Root exudation (1) stimulates growth of a diverse bacterial community (2) and subsequently of bacterial-feeders such as protozoa (3). Ammonia is excreted by protozoa and selective grazing favours nitrifiers and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA+) producing bacteria (4). The release of signal molecules (5), such as NO3 - and IAA, induces lateral root growth (6), leading to release of more exudates (7), subsequent bacterial growth (8), etc. From Bonkowski 2004, reproduced with permission from New Phyologist

Ecological Significance and Conclusion.The immense number and diversity of organisms within the rhizosphere depend on intricate feedback loops involving the quantity and quality of rhizodeposits, interactions within the food web, and underlying soil properties (Fig. 2.23). Due to these complex interactions between soil, roots, microbes, and fauna, the rhizosphere possesses properties essential for plant nutrition and overall ecosystem functioning. It is a confirmed hot spot for biogeochemical transformations and element fluxes, warranting special attention in studies on nutrient cycling and climate change. Moreover, soil stabilized by root networks exhibits greater resistance to external stresses like erosion and flooding, highlighting the rhizosphere's critical role in soil conservation.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 121;