Forest Ecosystems: Soil Dynamics and Fungal Roles

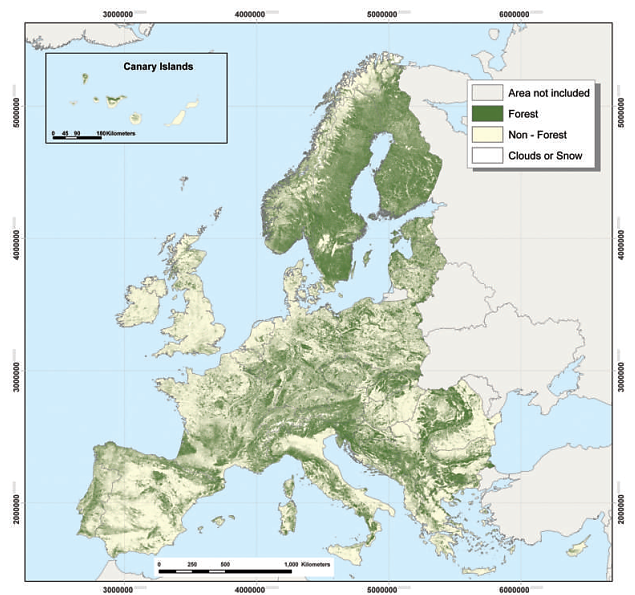

Forests represent species-rich terrestrial ecosystems that thrive under a vast array of climatic, geographic, ecological, and socioeconomic conditions (Fig. 3.1). In Europe, the total area of forests and other wooded land spans approximately 177 million hectares, constituting about 42% of the continent's land area (Fig. 3.4). Ecologically, these forests are distributed across numerous vegetation zones, extending from coastal plains to the high-altitude Alpine zone. This diversity underscores the complex interplay between environmental factors and forest development.

Fig. 3.1: A Boreal Forest in Sweden

Fig. 3.4: A map showing forest cover in Europe

Human well-being is intrinsically linked to the world's forests, which deliver a comprehensive suite of benefits and ecosystem services. They are vital sources of fuel, building materials, food, and the raw materials for many pharmaceuticals. Crucially, forests play an indispensable role in the global climate and carbon cycle, regulate the water balance, and provide diverse habitats for countless species. They also mitigate natural disasters such as floods, droughts, and landslides, while serving as a cornerstone for economic welfare and rural development by providing employment for millions.

The process of soil formation is profoundly influenced by climate, local geology, and vegetation cover (see Section 4.2). Forest soils are as varied as the forests themselves, ranging from shallow to deep and from nutrient-rich to poor. The tree canopy significantly impacts the soil building process; roots penetrate and fracture bedrock, while fallen leaves contribute organic matter. Furthermore, the canopy intercepts rainfall, and root systems stabilize the soil, collectively reducing soil erosion.

The specific type of forest dictates soil characteristics. In temperate forests, over 70% of the biomass, including leaves and twigs, falls to the ground annually (Fig. 3.2). This material is decomposed primarily by fungi and some bacteria, releasing nutrients back into the soil for reuse in a critical segment of the carbon cycle (see Section 5.1.3). Consequently, soils in temperate deciduous forests are typically rich due to this substantial annual organic input. Conversely, in coniferous forests, the litter layer consists of tough, slow-decomposing needles, leading to poorer, more acidic soils. The most impoverished forest soils are often found in tropical rainforests, where heavy rainfall leaches nutrients away.

Fig. 3.2: Fallen leaves provide a large annual input of organic material into the soil of deciduous forests around the world

Forest soils fundamentally differ from agricultural soils because their formation is dominantly influenced by forest vegetation and its associated soil organisms. They are generally more acidic, feature well-developed organic layers, and possess a higher organic content. While grassland soils incorporate organic matter within the root zone, forest soils accumulate a significant amount on the surface, where it gradually decomposes into humus (see Section 2.3). The formation of forest soils is also a slower process, taking an average of 1,000 years to form 25 mm of soil, compared to about 500 years under agricultural conditions.

A key distinction is that forest soils are relatively undisturbed, containing high levels of lignin and other recalcitrant materials from litterfall. This environment favors fungal dominance over bacteria, as disruptive activities like tilling, which destroy fungal hyphae networks, are absent. In pristine forest floors, there can be thousands of kilometers of hyphal filaments per gram of leaf litter. The mycelial component in the topsoil of a typical Douglas fir forest may constitute up to 10% of the total soil biomass, an estimate that may even be low considering the mass of endomycorrhizae and other fungi.

Fungi are paramount in forest soils due to their unique ability to decompose resilient substances like wood. While many microbes can break down cellulose, only specific fungi can fully degrade lignin, the polymer that gives wood its structural integrity. Without brown rot fungi, which break down cellulose, and white rot fungi, which degrade lignin using oxidizing enzymes, plant material would not decay, and essential soil nutrients would remain locked in accumulating biomass.

An equally critical role is played by mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with tree roots. This mutualistic association is so vital that approximately 80% of all terrestrial plant species depend on it. The fungus exchanges enhanced mineral and water absorption capabilities, as well as increased drought tolerance, for carbohydrates from the host plant. The two most common groups in forest soils are ectomycorrhizal fungi, which form a sheath around root cells, and endomycorrhizal fungi, whose hyphae penetrate the root cells. A forest's health is directly correlated with the presence and diversity of these fungi.

Some mycorrhizal fungi are also prized food sources. The most renowned is the truffle, the fruiting body of ectomycorrhizal fungi from the genus Tuber. Famous species include Italy's white truffle (Tuber magnatum) and the French black truffle (Tuber melanosporum). These subterranean delicacies, located near host trees using trained dogs, are difficult to cultivate, contributing to their high value.

Fig. 3.5: Fruiting bodies of Amarillaria ostoyae (AR)

Not all fungal relationships are beneficial. Pathogenic fungi, such as those from the genus Armillaria (honey fungus), are destructive parasites (Fig. 3.5). This pathogen spreads via black rhizomorphs, or "bootlaces," and is devastating because it continues to thrive on dead host material. Its destructive potential is exemplified by a colony of Armillaria ostoyae discovered in Oregon, which spread over 890 hectares and was estimated to be 1,500-2,400 years old. Comprising genetically identical cells from a single spore, it is considered the world's largest and oldest known living soil organism.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 92;