Grassland Ecosystems: Biodiversity, Soil Dynamics, and Management Impacts

Grasslands represent one of the planet's most extensive and successful vegetation types, covering approximately 25% of the Earth's terrestrial surface (Fig. 3.13). A key physiological trait of most grass species is their intolerance for shade, creating a historic competition with forests, which suppress grass growth under their dense canopies. Fossil evidence suggests grasslands first emerged in the late Cretaceous period, around 100 million years ago, likely establishing at high altitudes above the tree line. At that time, vast forests dominated the landscape, limiting the initial spread of grass-dominated ecosystems. These ecosystems have played a foundational role in human history, serving as grazing lands for over 7,000 years and as the origin for the domestication of commercial cereals like wheat and barley.

Globally, grasslands are classified into two broad categories: tropical/sub-tropical and temperate. Tropical grasslands include the savannahs of Africa, characterized by scattered trees, and shrublands dominated by woody plants, such as those found in Australia's Nullarbor Plain. Temperate grasslands encompass the vast prairies of North America and the steppes of Europe, which can be further subdivided based on dominant flora. Additional distinctions include high-altitude Alpine grasslands and the classification between natural grasslands and secondary grasslands, which form after human landscape modification (Fig. 3.15).

Fig. 3.15: Two semi-natural grasslands. The photo on the left shows grassland used for grazing in the Peak District of northern England. The photo on the right shows an alpine grassland in Northern Italy which is over 2,000 metres above sea level

The soil profile of natural grasslands is typically deep and nutrient-rich, a direct result of the annual die-off of substantial plant tissue that builds up as soil organic matter. These deep, fertile soils are one reason why few pristine grasslands remain; most have been converted for agriculture or intensive livestock grazing. For instance, North American grasslands are still being converted to arable land at a rate of over 2.5 million hectares per year. Despite this, the below-ground life in grasslands is extraordinarily abundant and diverse, often exceeding above-ground biomass and species richness. A study in Northern Italian grasslands found 35,000 Acari (mites) and 30,000 Collembola (springtails) per square meter, densities 10 to 20 times higher than in adjacent woodlands.

A defining feature of grassland biomes is their simple structure coupled with exceptionally high species richness, particularly below ground. It is estimated that a single hectare of temperate grassland can support approximately 100 tonnes of living biomass beneath the surface, comprising bacteria, fungi, earthworms, microarthropods, and insect larvae. This immense biomass is equivalent to a stocking rate of 2,000 sheep per hectare, far exceeding typical above-ground rates. The diversity is equally staggering, with tens of thousands of bacterial species, thousands of fungal species, and hundreds of insect and worm species inhabiting just one square meter of soil.

The soil biota is critical for grassland ecosystem health. Controlled experiments demonstrate that the absence of key decomposers like Collembola and earthworms leads to a significant decrease in both total plant and root biomass. The most pronounced negative effects occur when both organism groups are absent. Conversely, the presence of both leads to a synergistic increase in root biomass, highlighting that the interactions between soil organisms are just as important as their individual presence for overall plant health and productivity.

Most modern grasslands are managed through practices like grazing, mowing, or reseeding with specific species to create improved pasture (Fig. 3.16). A common example is tall fescue grass (Lolium arundinaceum), a perennial species often grown for forage and lawns. This grass typically forms a symbiosis with a fungal endophyte, Neotyphodium coenophialum. Certain genetic strains of this fungus produce alkaloids that are toxic to herbivores, while other strains of the same species do not. Research shows that inoculating the grass with different mycorrhizal fungi can alter its behavior, reducing its aggressiveness and seed production, thereby allowing other plants to coexist.

Fig. 3.16: An irrigated grassland area from northern Italy

The above four images show the global cover of grasslands shown in green. The images were produced by NASA using data obtained from Terra/MODIS/Land Cover at a 1 km resolution. (Images courtesy of NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Scientific Visualization Studio.)

Fig. 3.18: An area of improved pasture in Ballintium, Perthshire, U.K. (foreground) contrasted against a non-treated grassland area in the background

The conversion of native pasture to improved pasture, often involving high-value grasses and clovers (Fig. 3.18), has profound effects on soil biota. The impact severity depends on the management intensity and the similarity between the original and new ecosystem. Generally, improved pastures can increase earthworm biomass and species richness compared to native pastures. However, they often favor introduced species of Collembola at the expense of native species, as observed in Australian studies. This management can also co-introduce invasive soil organisms, such as pathogenic fungi. Therefore, while improved pastures boost animal productivity and some ecosystem services, careful management is required to mitigate negative ecological consequences and protect native soil biodiversity.

Tropical vs Temperate Soil Biodiversity: Organisms, Functions & Differences

Soils represent some of the most biologically rich habitats on Earth, a reality that holds true for both temperate soils of regions like Europe and the tropical soils found in South America, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia. This analysis highlights key similarities and differences in soil biodiversity between these zones, acknowledging that the immense diversity of tropical regions cannot be covered in its entirety. A single site in the Brazilian Amazonian rainforest can harbour several thousand invertebrate species, a total likely exceeding that of a similarly sized site in a Central European deciduous forest. However, the disparity in soil biodiversity between temperate and tropical regions is less pronounced than in above-ground ecosystem compartments, such as the forest canopy. The enormous number of organisms in tropical soils is partly attributable to the vast geographical size of these regions combined with a high degree of endemism, where many species exist only in very restricted areas.

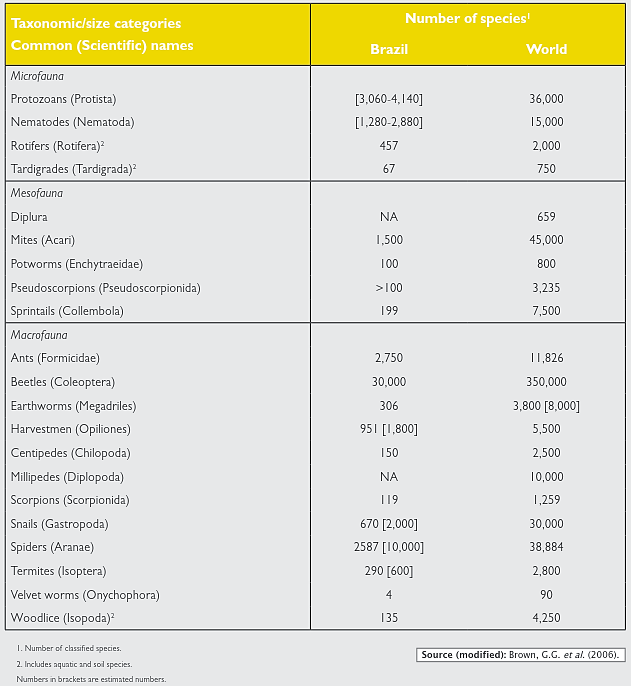

Table 3.1: The number of soil species found in Brazil compared to the rest of the world

The sheer scale of tropical soil life is exemplified by Brazil, where over 50,000 species of soil and litter-inhabiting animals have been formally described (Table 3.1). While a few species are of giant size, such as certain earthworms (Fig. 3.19), the vast majority are microscopic, like nematodes, or very small insects such as beetles and ants. Furthermore, tropical soils support exceptionally high levels of fungal diversity (Fig. 3.20), which plays a critical role in nutrient cycling. To an even greater extent than in European soils, the majority of tropical soil organisms remain unknown to science. It is estimated that only 3-5% of the world's predicted diversity of nematodes and mites has been documented. A significant bottleneck is the global shortage of taxonomic specialists capable of identifying these organisms, a problem that is particularly acute for the tropics, as the most important reference collections are housed in European and North American museums.

Fig. 3.19: Giant earthworm (Rhinodrilus priolli) from the Brazilian Amazon

Fig. 3.20: Fungus of the litter layer in the Brazilian Mata Atlantica, with a small fly inside

This profound lack of knowledge has led soil communities to be termed the “other last biotic frontier.” The total number of species living in the soil, in both tropical and temperate regions, remains a mystery. The incredibly complex tropical soil system, with its high numbers of interacting microbial, animal, and fungal species, provides a vast range of ecological functions and ecosystem services to humanity. These services, including food provision and climate regulation, have an estimated economic value running into billions of euros annually. Despite this value, tropical soil ecosystems face growing stress from land-use changes, such as forest clearing for biofuel plantations, exacerbated by a fundamental lack of understanding.

Key Examples of Tropical Soil Biodiversity. While the major groups of soil organisms are similar in European and tropical regions, several key differences exist. The most obvious is the occurrence of giant earthworms, which can reach lengths of one to two metres. However, these giants typically occur in small numbers and do not exert the same dominant influence as the "ecosystem engineer" earthworms commonly found in European soils. Conversely, even small earthworm species can have massive global impacts. The species Pontoscolex corethrurus, originally from northern South America, has invaded most of the world's tropical regions over the last six hundred years (Fig. 3.21). In high numbers at cleared rainforest sites, its intense cast production can seal the soil surface, preventing water infiltration and negatively impacting plant growth.

Fig. 3.21: Juvenile and adult specimen of the species Pontoscolex corethrurus

Another influential species, Enantiodrilus borellii, dominates the landscape of East Bolivian savannahs with its cast "towers" that can reach 30 cm in height, an adaptation to the regular flooding in the Beni Province (Fig. 3.24). This large-scale cast production has been shown to have positive effects on plant growth and the diversity of other soil organisms. Similarly, the anecic earthworm Martiodrilus sp. from the Colombian “Llanos” provides such vital soil functions that its removal has been demonstrated to cause significant problems within the soil ecosystem (Fig 3.25). A more significant difference from European soils is the pronounced dominance of social insects in the tropics, particularly termites in savannahs and ants in forests. Their sporadic distribution, with huge numbers at nesting sites but few individuals between them, makes them challenging to study, and some species have adapted to become pests in human settlements.

Fig. 3.24: Cast towers of one earthworm species after the end of the flooding season (Beni, Bolivia)

Fig. 3.25: Impermeable layer of earthworm casts (grey zone) at the soil surface of a recently cleared forest site now used as meadow

Termites are integral to tropical terrestrial ecosystems, inhabiting all vegetation layers and various soil strata, from the litter layer deep into the mineral soil. Their nests are among the largest structures built by invertebrates, reaching several metres in both diameter and height, and housing millions of individuals from different castes like workers and soldiers. Termites primarily feed on wood, a resource they can digest thanks to symbiotic microbes in their gut. Their role in biogeochemical cycles is significant, as they contribute approximately 4% and 2% of global methane and carbon dioxide emissions, respectively, making them a key subject in greenhouse gas research. However, exceptions exist; in the Colombian "Llanos," the integrated annual methane flux from termite mounds was found to be a negligible 0.0004% of the global total, as the methane is largely oxidised in the soil before reaching the atmosphere.

The positive impacts of termites on soil structure and properties are profound due to their high activity and biomass. In rainforests, an average of 100 termite species can be found per hectare. In some regions, like Africa's Sahel zone, termites are even artificially introduced to degrade fine wood matter and produce compost for agricultural fertilizer. The diversity of ants in tropical regions, especially rainforests, is also extraordinarily high. More than 500 species can occur within a 10-square-kilometre area. Globally, 12,513 species have been described, with about 25% found in South America alone. Astonishingly, 114 species were documented in a single 10 x 10 metre soil plot in Peru, and 82 species were collected from a single tree in the Brazilian Amazon, underscoring the hyper-diverse nature of these ecosystems.

Soil Biota, Agriculture & Ecosystem Health: Impacts and Benefits

Humanity's 10,000-year history of farming has, until now, largely succeeded in feeding a growing global population. Particularly over the last half-century, a rapid technological revolution has enabled farmers in many regions to markedly increase total crop yields. This agricultural intensification relied on new technologies including agricultural chemicals, advanced mechanization, and sophisticated plant breeding, supported by resource availability and productivity-focused policies. Unfortunately, this intensification has often carried a significant environmental price, resulting from the overuse of inputs, practices that degrade soils, and the mismanagement of natural resources.

In contrast to these intensive systems, extensive, or low-input, agriculture remains prevalent in many parts of the world. These systems are typically small-scale, labour-intensive, and employ relatively simple technologies. When practiced under growing population pressure, the opportunity to restore soil fertility through traditional fallow periods diminishes significantly. Ultimately, improper agricultural practices in both intensive and extensive systems can lead to severe impacts on the environment, ecosystems, human health, and economies, creating a cycle of land degradation.

Undesirable Impacts of Improper Agricultural Practices. The negative consequences of unsustainable farming are multifaceted and interconnected. A primary impact is the severe deterioration of soil quality, manifesting as increased erosion, depletion of organic matter, reduced soil fertility, salinisation, and compaction, all leading to less productive land. Furthermore, the pollution of soil and water resources occurs through excessive fertilizer use and improper disposal of animal wastes. The indiscriminate application of pesticides and chemical fertilizers also increases incidence of human and ecosystem health problems.

Agricultural practices also drive a significant loss of biodiversity at multiple levels. This includes a reduced number of cultivated species for commercial purposes and the extinction of locally adapted species, which results in a loss of valuable adaptability traits. This is compounded by the loss of beneficial crop-associated biodiversity that provides critical ecosystem services such as pollination, nutrient cycling, and pest regulation. Finally, unsustainable irrigation practices cause soil salinisation and freshwater depletion, while intensive tillage and slash-and-burn methods disturb fundamental soil physicochemical and biological processes.

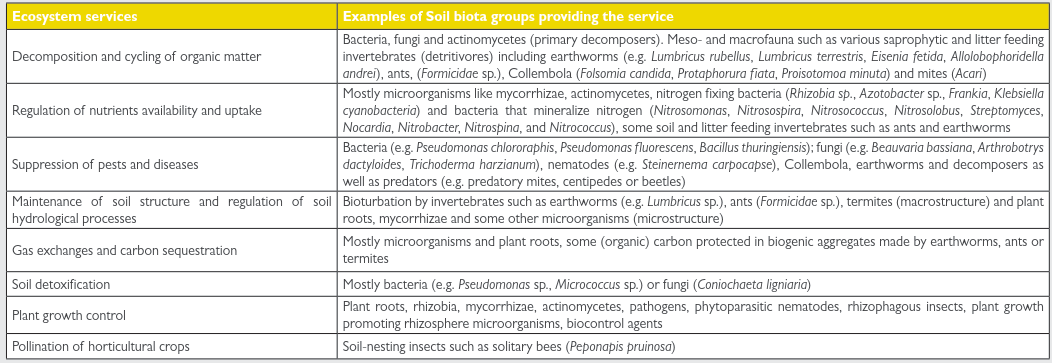

The Critical Roles of Soil Biota in Ecosystem Health. Scientific understanding has firmly established that the complex processes carried out by the soil biota—which includes plant roots—profoundly influence ecosystem health, soil quality, and the incidence of soil-borne diseases. These biological activities directly affect crop quality and yields. Over recent decades, researchers have unveiled the specific roles of various soil organisms in regulating soil fertility and plant production. While many interactions, particularly between above-ground and below-ground biota, remain poorly understood, numerous examples illustrate both the positive and negative effects specific organism groups have on agricultural productivity. The essential ecosystem services provided by these organisms are detailed in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2. Essential ecosystem services provided by soil biota (modified from Bunning and Jiménez, 2003)

The Function of Soil Biota in Maintaining Soil Fertility. A primary service of soil organisms is the decomposition and cycling of organic matter. Farmers apply materials like crop residues, manure, and compost to fields as nutrient sources. The soil biota then transforms these inputs into energy and plant-available nutrients. Decomposers are the key organisms responsible for these fundamental processes, which are crucial for conserving soil quality. This diverse functional group includes several main categories, each with a unique role in the breakdown cycle.

The microflora, comprising certain bacteria and fungi, act as the primary decomposers, digesting complex organic matter into simpler substances. The microfauna, including protozoa and nematodes, subsequently feed on these microbes, assimilating their tissues and excreting mineral nutrients. Mesofauna, such as mites (Acari), springtails (Collembola), and potworms (Enchytraeidae), break up plant detritus and regulate microbial communities through their feeding activities. Larger macrofauna, including ants, termites, and earthworms, mix organic matter into the soil profile, thereby improving resource availability for the microflora.

A key outcome of this decomposition process is the formation of humus, a stable class of organic substances (see Section 2.3). Humus acts as a long-term reservoir of soil fertility and is essential for creating stable soil structure and regulating water movement. In conclusion, decomposers are fundamental to the biosphere, and their processes are crucial for maintaining all life. Within agriculture, they directly contribute to improved yields by mineralizing organic matter and unlocking vital nutrient reservoirs for plant growth.

Soil Biota & Nutrient Cycling: Nitrogen Fixation and Mineralization

The successful growth of plants depends on the availability of 16 essential nutrients, which crops can only absorb from the soil in specific, soluble forms. A complex interplay of chemical, physical, and, crucially, biological processes governs the availability of these elements. The processes carried out by the soil biota are fundamental for maintaining high crop production and achieving optimal yields. Furthermore, these biological systems provide a vital means of plant nutrition in areas where access to or use of chemical fertilizers is impractical. The following sections detail how soil organisms create nutrient pools and regulate the availability of key elements, with a focus on the critical nutrient, nitrogen.

Nitrogen Availability: A Key to Plant Growth. Nitrogen is the most important limiting nutrient for plant growth, directly responsible for vigorous growth, branching, tillering, leaf production, and final yield. However, plants can only utilize nitrogen in specific forms, primarily ammonia and nitrate, which are made available through the transformation of more complex compounds by the soil biota. Soil nitrogen deficiency is a common challenge in both tropical and subtropical agroecosystems. Finding efficient methods to acquire and use nitrogen is therefore paramount for crop production in these regions. Concerns over finite fossil fuel reserves for fertilizer production and rising costs are also driving the need for alternative plant nutrition strategies, elevating the importance of soil biota in providing nitrogen.

Biological Nitrogen Fixation (BNF). Several groups of soil microorganisms possess the unique ability to convert inert gaseous nitrogen from the atmosphere into plant-usable ammonia, a process known as Biological Nitrogen Fixation (BNF). This process occurs in soils, water, on or within plant tissues, and even in animal digestive tracts. Global estimates for terrestrial BNF range from 100 to 290 million tonnes of nitrogen per year, with agroecosystems contributing 40-48 million tonnes. This highlights the substantial contribution of BNF to global crop production, carried out by both symbiotic microorganisms living in association with plants and non-symbiotic (free-living) microorganisms in the soil.

Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing microorganisms, such as bacteria from the genus Rhizobium, form associations with the roots of legumes like soybeans, lentils, and peanuts (Fig. 3.22). This relationship can fix between 30 to 300 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare annually. To ensure effective nodulation, farmers often coat seeds with a bacterial inoculum before sowing (Fig. 3.27), a practice essential in soils where native populations are inadequate. In contrast, non-symbiotic nitrogen fixation is performed by free-living bacteria like Azotobacter (aerobic) and Clostridium (anaerobic), as well as cyanobacteria such as Anabaena. While globally significant, the amount of nitrogen fixed by non-symbiotic organisms in a given area is typically lower than that achieved by symbiotic systems.

Fig. 3.27: Rice fields in Austria having been treated with Azolla bio-fertilizer which has been found to give the same yields as those treated with chemical nitrogen fertilizers

Nitrogen Mineralization and Nitrification. The conversion of organic nitrogen within soil organic matter into inorganic, plant-available forms is called nitrogen mineralization. This process begins with ammonification, where microorganisms decompose proteins and amino acids into ammonium. While microbes use some of this ammonium for their own growth, they often release the excess into the soil, making it available for plant uptake or for the next critical step: nitrification. In many non-acidic soils, most plants prefer nitrogen in the form of nitrate, requiring the conversion of ammonium through nitrification.

The nitrification process is a two-step microbial mediation. First, specialized bacteria, including Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira, convert ammonia into nitrite. Subsequently, other bacteria, such as Nitrobacter, oxidize the nitrite into nitrate, the form most readily absorbed by many crops. Emerging research also suggests that archaea play a previously underestimated role in these nitrogen cycle processes, though their precise interactions are still being fully explored.

The Role of Macrofauna in Nutrient Dynamics. Macrofauna, particularly earthworms, play a major role in soil nutrient dynamics by physically modifying the soil environment. Their activities, such as burrowing and casting, alter soil porosity, aggregate structure, and the distribution of organic matter. This, in turn, influences the composition, biomass, and activity of microbial communities. Earthworm casts and burrows create highly favourable microsites for microbial activity, and their excreta (ammonia, urea) and body tissues are rapidly mineralized. It is estimated that earthworm populations in agroecosystems can contribute significantly to nitrogen fluxes, releasing between 10 to 74 kg of nitrogen per hectare per year through their vital ecosystem engineering.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 102;