Peatlands: Unique Biodiversity Islands and Their Ecological Significance

Peatlands are globally unique soil ecosystems defined by the accumulation of partially decomposed plant matter, known as peat (Fig. 3.6). Unlike most soils, the primary production in these areas is not fully decomposed or utilized, leading to organic matter buildup. A critical feature is perpetual water saturation and a general lack of direct mineral input. While some peatlands, like fens, receive nutrients from groundwater, others, such as bogs or mires, are ombrotrophic and rely solely on atmospheric precipitation. These constraining conditions collectively shape the distinctive biological diversity found within these environments, resulting in ecosystems of high conservation value.

Fig. 3.6: A peatland landscape in Lahemaa National Park, Estonia

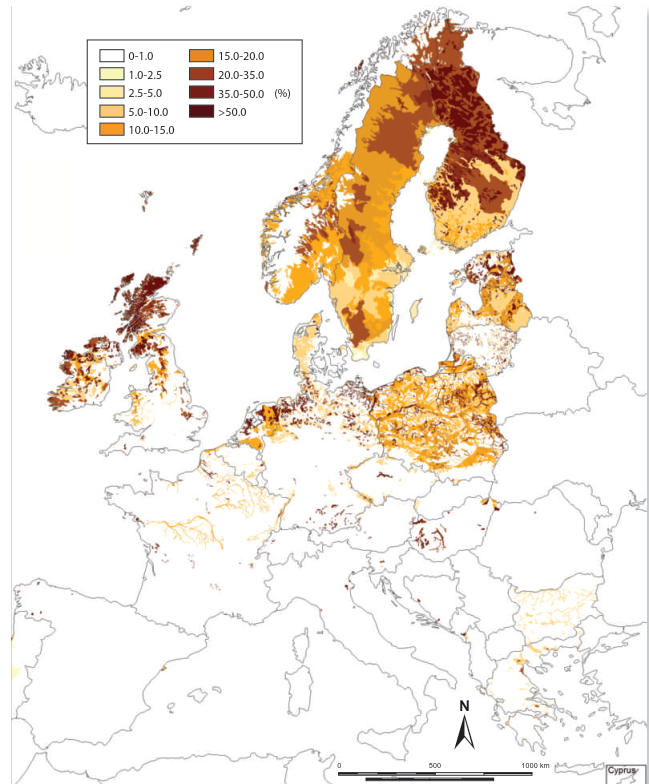

The accumulation of peat is contingent upon sufficient soil moisture to inhibit decomposition processes. Consequently, its global distribution strongly correlates with high-latitude regions where precipitation exceeds evapotranspiration (Fig. 3.7). Significant tropical peatlands also exist in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. Permanent waterlogging has driven the evolution of unique plant adaptations. Many vascular species develop specialized aerenchymatous tissue to facilitate gas exchange in oxygen-poor substrates. The nutrient-poor, wet conditions are ideal for bryophytes, particularly Sphagnum mosses, which lack true roots. Some species, like the rush Empodisma minus in New Zealand, even possess negatively geotropic roots that grow upward to form a dense nutrient-capturing mat on the peat surface.

Fig. 3.7: Relative cover (%) of peat and peat-topped soils in the Soil Mapping Units (SMUs) of the European Soil Database

Nutrient scarcity, especially of nitrogen, has fostered remarkable evolutionary adaptations among peatland flora. A prominent strategy is carnivory, exhibited by plants like the sundews (Drosera spp.) and the pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea), which is native to North America but now naturalized in Europe (Fig. 3.9). These species supplement their nutrient intake by digesting captured insects. Furthermore, many bryophytes form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria to overcome nutrient limitations. For most other plants in ombrotrophic systems, where nutrients are locked in organic matter, acquiring essential elements requires sophisticated biological partnerships.

Fig. 3.9: Photo of the Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia purpurea, a carnivorous plant which is native to North America but which can now be found in various peatlands across Europe

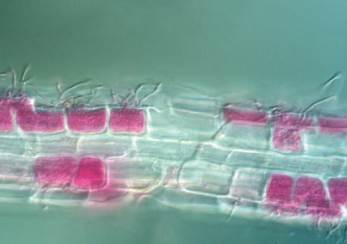

A primary adaptation to nutrient limitation is the formation of intimate symbioses with fungi. Ericaceous plants, such as Rhododendron and Calluna, form ericoid mycorrhizal associations. The fungal partners, all ascomycetes that seldom produce visible fruiting bodies (Fig. 3.8), envelop the root cells. These fungi possess unique enzymatic capabilities, positioning them between saprotrophic decomposers and purely mutualistic mycorrhizas, which allows them to liberate nutrients from complex organic matter. Until recently, the sedge family was considered an exception, relying on specialized dauciform roots for nutrient uptake. However, evidence now shows sedges also associate with dark septate endophytes, though their functional role remains under investigation.

Fig. 3.8: Image showing ericoid mycorrhizal structures (stained red) penetrating inside root cells

The fungal community in peatlands includes numerous unique and specialized species. Examples include the bog beacon (Mitrula paludosa), named for its distinctive fruiting body shape (Fig. 3.10), and Sarcoleotia turficola, which is predominantly associated with Sphagnum moss (Fig. 3.12). The lichenized fungus Omphatina ericetorum is also commonly found in these habitats (Fig. 3.11). These ecosystems can also serve as refuges for rare and threatened fungi, such as Armillaria ectypa, the marsh honey fungus. This bioluminescent species is on the UK's provisional Red List and is thought to contribute to the eerie "will-o'-the-wisp" light phenomena observed at night, potentially caused by methane ignition.

Fig. 3.10: Fruiting bodies of Mitrula paludosa, The Bog Beacon

Fig. 3.11: Fruiting body of the lichenous fungus Omphalina ericetorum

Fig. 3.12: Fruiting bodies of the fungus Sarcoleotia turficola

Methane production in the anaerobic layers of peatlands is among the highest of all global soil types. This methane is a byproduct of methanogenic archaea. A key natural recycling pathway is methane oxidation, performed by specialized bacteria. These methane-oxidizing bacteria are most active in oxic microsites, often clustering around plant roots where oxygen diffuses into the otherwise waterlogged peat, mitigating the release of this potent greenhouse gas into the atmosphere.

The role of peatlands in climate change is profoundly significant due to their vast carbon storage capacity. When bogs are drained, the previously anoxic peat is exposed to oxygen, enabling microbial decomposition that converts stored carbon into carbon dioxide (CO2). Additionally, the anaerobic conditions naturally lead to the annual emission of approximately 30 megatonnes of methane globally. This creates a critical feedback loop between land use, climate change, and soil biodiversity, a relationship explored in greater detail in Section 5.1.3.

Beyond specialized flora and fungi, peatlands support distinctive invertebrate communities. For instance, enchytraeids (potworms) and dipteran larvae can reach exceptionally high population densities. Protozoan communities are also well-represented, particularly testate amoebae (Rhizopoda; Fig. 3.13). The species composition of these amoebae is so closely tied to environmental conditions like pH and moisture that they are extensively used in paleoecological studies to reconstruct past climates.

Fig. 3.13: Testate amoeba such as those from the genus Nebela are common in peatland environments

Fig. 3.14: While amphibians may not generally inhabit peatlands all year around, they can be essential refuges for some species such as frogs and other amphibians at times of harsh summer or winter conditions

These ecosystems also provide crucial seasonal refuge for larger fauna. Amphibians, for example, may use peatlands for survival during harsh summer or winter conditions (Fig. 3.14). The interdependence of species can be extremely intimate, making them vulnerable to habitat alteration. A notable example is the newly described moth Houdinia flexilissima, whose caterpillar stage lives exclusively within the stems of the cane rush (Sporadanthus ferrugineus) in New Zealand. Both species are now endangered due to their limited distribution and habitat threats. Therefore, peatlands function as unique biodiversity 'islands,' fostering high species uniqueness and offering refuge for specialized taxa, albeit at the expense of overall species richness.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 81;