Biocontrol and Biological Pest Control: Strategies, Agents, and Soil Biodiversity

Biocontrol of pests, also known as biological control, is a strategy utilizing natural enemies as biological control agents. These agents include predators, parasites, and pathogens deployed to suppress target pest populations. It serves as a sustainable alternative to broad-spectrum chemical pesticides, mitigating their associated environmental risks (Fig. 4.22). Such pesticides are problematic because they indiscriminately harm beneficial insects and can leach into groundwater, causing contamination.

When the target pest is a plant disease pathogen, the controlling agent is specifically termed an antagonist. Biological control strategies are formally categorized into three primary types. Conservation involves modifying practices to protect and enhance existing natural enemy populations. Classical biological control entails the intentional introduction of an exotic natural enemy to control an invasive pest.

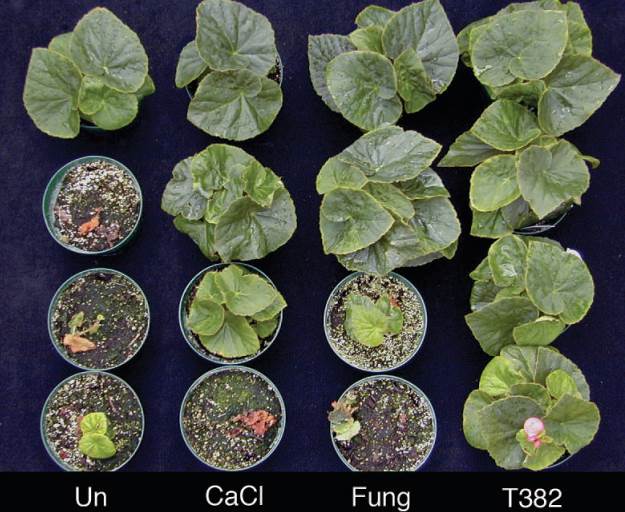

Fig. 4.22: An example biocontrol bioassay for biological control of the plant pathogen Botrytis cinerea. The begonias were grown in a greenhouse under optimum conditions for the development of the pathogen. Treatments differing in their efficacy are shown, from left to right: untreated control (Un), CaCl2, a fungicide (Fung), and a fungus as a biocontrol agent Trichoderma hamatum (strain T382). Clearly the biocontrol agent shows the best results with the plants protected from the pathogen by this fungus producing the most foliage

The third strategy, augmentation, involves the supplemental release of mass-reared biological control agents to boost local populations. A prominent example is the application of entomopathogenic nematodes against soil-dwelling insect larvae, often released at scales of millions per hectare. This approach provides immediate pest suppression in agricultural and horticultural systems.

The selection of effective biocontrol organisms follows established criteria. An ideal agent, as outlined by Kerr (1982), must persist in the soil environment, either actively or in a dormant state. It must reliably contact the target pathogen, either directly or via diffusable antagonistic compounds. Furthermore, laboratory mass production must be both simple and cost-effective to facilitate commercial viability.

Additional key characteristics include safe, inexpensive packaging and application methods. High specificity to the target pest is desirable to minimize ecological disruption. The agent must pose no health hazard and remain active under the same environmental conditions as the pest. Ultimately, it must provide efficient and economical control to be a practical alternative to chemicals.

Soil biodiversity represents an invaluable reservoir for broader biotechnological innovation beyond biocontrol. Numerous microbial-based products are already established, with hundreds more in development. Scientific consensus holds that microbial diversity remains largely unexplored; advances in microbial isolation methods promise to reveal novel metabolic pathways and compounds.

Progress in molecular biology and strain improvement techniques will further enhance product development. This includes the creation of novel microbial strains addressing global challenges like food security, pollution, and disease. Agricultural biotechnology has already yielded crops with increased pest resistance and nutritional value, such as Golden Rice.

The field of renewable energy also benefits from soil microorganisms. The bacterium Ralstonia metallidurans is studied for fuel cell applications due to its metal-precipitating abilities. Soil microbes are a promising source for biogas and biofuels like bioethanol and biodiesel. Bioethanol production leverages microbial fermentation of sugars and, increasingly, cellulose, often using genetically optimized 'superstrains'.

However, genetic manipulation and biotechnology applications are not without controversy and potential drawbacks. Strict regulations aim to minimize hazards associated with transgenic organisms, including threats to human health and natural biodiversity. Despite limited conclusive evidence of these risks, precautionary principles guide policy, driving interest in harnessing natural biodiversity directly.

The conservation of soil microbial diversity is thus an urgent priority from both ecological and biotechnological perspectives. Soils, the primary reservoir of this diversity, face escalating threats from anthropogenic activities. Each microbial extinction potentially represents the loss of an undiscovered biotechnological solution. Therefore, raising awareness within the scientific community, among policymakers, and the public is critical.

Preserving soil biodiversity is essential for sustaining environmental health, enriching human potential, and securing a pipeline for future innovation. Its conservation and judicious exploitation are paramount issues that require coordinated global attention and responsible stewardship for generations to come.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 114;