Understanding Suppressive Soils: Mechanisms, Examples, and Biocontrol Applications

A soil is termed suppressive when, despite otherwise favorable conditions for disease, a pathogen fails to establish, causes minimal damage, or initiates disease that subsequently declines. In contrast, conducive soils readily support disease development. This soil suppressiveness is intrinsically linked to soil fertility, physical-chemical nature, and, most critically, its microbiological activity. The phenomenon is categorized into two primary types: general suppression and specific suppression.

General suppression arises from a high total microbial biomass and biodiversity, creating an environment broadly unfavorable for pathogen proliferation. Specific suppression is attributed to the actions of individual or select groups of microorganisms that antagonize pathogens at particular life cycle stages. This specific form is transferable to conducive soils with an effectiveness ranging between 0.1% and 10%. Both types are primarily biological in origin, as evidenced by their elimination through soil autoclaving or gamma radiation.

The biological basis of suppressiveness is further clarified by differential heat tolerance. General suppression is reduced but not eliminated by soil fumigation and can withstand moist heat at 70°C, owing to the high functional redundancy within a diverse community. Specific suppression, reliant on fewer microbial species, is eliminated by pasteurization (30 minutes at 60°C), indicating lower functional redundancy. In practice, most suppressive soils derive their activity from a combination of both general and specific mechanisms acting in concert.

Beneficial microorganisms in these soils employ multiple antagonistic strategies, including nutrient competition, direct parasitism, production of antibiotic metabolites, and induced systemic resistance in plants. Among these, fluorescent pseudomonads are often highlighted. Their role is linked to siderophore-mediated iron competition (e.g., in soils suppressive to Fusarium wilts) and antibiosis (e.g., in soils suppressive to take-all). The most widely studied examples of this phenomenon are Take-all decline (TAD) and Fusarium wilt-suppressive soils.

Take-all, caused by the fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, is a major global wheat disease. TAD describes the spontaneous reduction in disease severity after several years of wheat monoculture. This globally observed phenomenon involves various microbial antagonists, with fluorescent pseudomonads playing a key role worldwide. These bacteria, classified as Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR), synthesize antifungal compounds like 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG) that inhibit the pathogen, and their populations increase significantly on infected roots.

Fusarium wilts, caused by Fusarium oxysporum formae speciales, cause significant crop losses. Suppressive soils studied in locations like Châteaurenard, France, and California's Salinas Valley, USA, show activity associated with non-pathogenic F. oxysporum and fluorescent Pseudomonas species. These microbes compete for carbon and iron, respectively, and can induce plant resistance. Unlike other systems, suppressiveness to Fusarium wilt has sometimes been induced by continuously cropping partially resistant cultivars.

Some pathogens with large, resilient propagules, like Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii, are not controlled by general suppression but are susceptible to specific antagonists. Trichoderma species, for example, locate, colonize, and parasitize these pathogens. The process involves Trichoderma hyphae coiling around the pathogen's mycelium, aided by lytic enzymes that degrade the cell wall, ultimately leading to the collapse of the pathogen cells (Fig. 4.15).

Fig. 4.15: Trichoderma harzianum parasitizing Rhizoctonia soiani hypha with pincers and hooks. (APi)

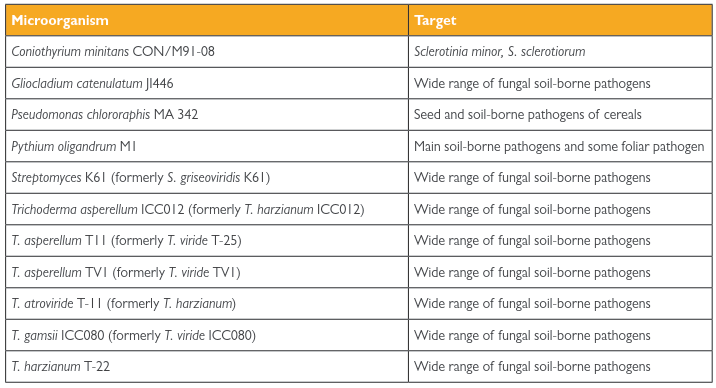

The delivery of Beneficial Microorganisms as Biocontrol Agents (BCAs) represents a strategic approach to managing soil-borne diseases. Research over the past century has identified a phylogenetically diverse reservoir of natural antagonists in soil. These BCAs interact with pathogens through antibiosis, competition, and parasitism, and can also induce systemic resistance in plants. Intensive screening programs have led to the commercialization of numerous bacterial (e.g., Streptomyces, Pseudomonas) and fungal (e.g., Coniothyrium, Gliocladium, Trichoderma) BCAs (Table 4.3), applied as seed treatments, soil inoculants, or drenches.

Table 4.3: Antagonistic fungi and bacteria included in Annex 1 of Directive 91/414/EEC and authorised at national level for the biological control of soil-borne diseases in several European countries. (Up to date March 2010)

Fig. 4.16: Colony of Trichoderma sp. on potato dextrose agar

BCAs offer distinct advantages, including compatibility with organic farming and Integrated Crop Protection (ICP) programs. They are typically more target-specific than broad-spectrum chemicals and can enhance soil biodiversity. This contrasts sharply with soil fumigation, such as with the now-banned methyl bromide, which creates a harmful biological vacuum prone to rapid pathogen recolonization. Notably, genera like Trichoderma (Fig. 4.16) and Gliocladium can survive fumigation at higher relative levels, allowing them to recolonize treated soils effectively. While the native microbial balance cannot be fully restored, proactive soil management can foster a new, functional equilibrium oriented toward sustainable disease prevention.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 103;