The Economic Valuation of Soil Biodiversity: Challenges and Frameworks for Ecosystem Services

The critical and diverse contributions of soil biodiversity to ecosystem health and human welfare are unequivocal. It underpins the generation of numerous essential ecosystem services, from nutrient cycling to climate regulation. Despite its paramount importance, soil biodiversity receives disproportionately less attention than other natural resources and faces extensive global degradation. This discussion focuses not on individual organisms, but on the value of the biodiversity collective. The disparity stems partly from the inherent complexity of soil ecosystems, which are poorly understood and difficult to measure due to their scale and intricate interactions. More fundamentally, the primary reason for its loss is systemic undervaluation, driven by its exclusion from decision-making processes and the absence of markets for most of the services it provides.

Many vital ecosystem services, such as waste recycling, carbon cycle regulation, and maintaining ecosystem resilience, possess "public-good" characteristics. In economic terms, a public good is both non-rival (one person's use does not diminish another's) and non-excludable (providers cannot prevent non-payers from benefiting). These properties make establishing markets and direct financial value highly problematic, as there is no mechanism to capture revenue from beneficiaries. Consequently, these indispensable services are often treated as free and infinite, leading to their neglect and overexploitation in favor of short-term, market-driven gains.

A further complication in valuation is the mismatch between private and social costs and benefits. Conservation of soil biodiversity typically benefits society at large through large-scale services like water purification. However, conservation efforts and costs frequently occur at a local level, such as a single farm. Without mechanisms to compensate private resource users for conservation, it is often more economically rational for them to maximize private yield, even at the expense of long-term biodiversity loss. The societal costs of degraded ecosystem services are then externalized, borne by the public rather than the individual decision-maker. Furthermore, biodiversity loss can be accelerated by well-intentioned but flawed government policies, such as subsidies that incentivize deforestation or practices leading to agricultural land degradation.

Environmental economists seek to measure the economic value of non-marketed ecosystem services to address this fundamental market failure. The driving belief is that without demonstrating concrete value to decision-makers, society will be unwilling to incur the opportunity costs of conservation—the foregone economic benefits from alternative land uses like intensive agriculture. Therefore, the goal of economic valuation is to impute a value for ecosystem services, thereby informing policy and guiding resource allocation toward greater long-term efficiency and sustainability across different land-use objectives.

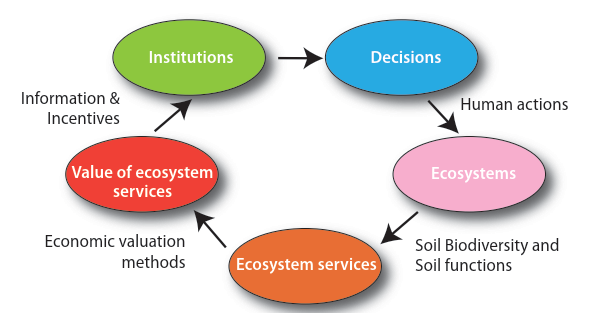

However, merely demonstrating economic value is a necessary but insufficient condition for ensuring sustainable use. It is equally critical to devise mechanisms for policymakers to integrate these values and for stewards to capture them. Various economic instruments have been implemented, including payments for ecosystem services (PES) for carbon sequestration, conservation easements, and debt-for-nature swaps. The success of any instrument depends on its integration into a robust, informed decision-making framework, as conceptualized in Fig. 4.23. This model illustrates that valuation is not an end goal but a tool to facilitate better decisions regarding land, water, and natural resource use.

Fig. 4.23: Decision loop to facilitate decision making regarding natural resources

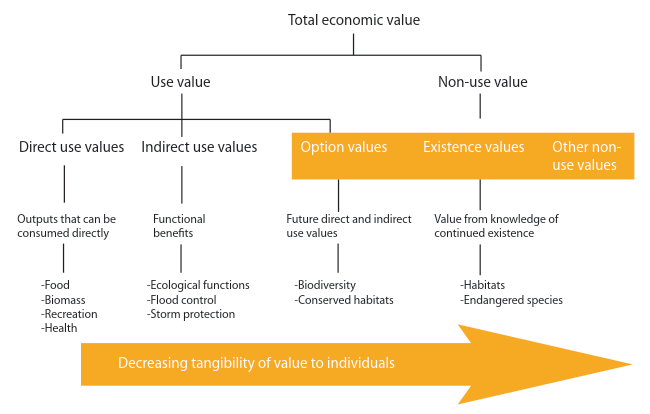

Total Economic Value (TEV) Framework. Economists commonly employ the Total Economic Value (TEV) framework to categorize the value of environmental assets, as depicted in Fig. 4.24. TEV comprises Use Value (UV) and Non-Use Value (NUV). Use Value arises from actual interaction with a resource and is subdivided into Direct Use Value (DUV) (e.g., harvesting timber or genetic resources), Indirect Use Value (IUV) (e.g., benefits from flood regulation or soil fertility), and Option Value (OV) (willingness to pay to preserve an option for future use). Non-Use Value includes existence value, held by individuals who value a resource's mere continued existence without any intent to use it.

Fig. 4.24: Schematic representation of Total Economic Value Framework

Thus, the relationship is defined as: TEV = UV + NUV = (DUV + IUV + OV) + NUV. In practice, while direct and indirect use values can be measured with relative success, quantifying option and non-use values remains challenging due to their subjective nature. The composition of TEV varies by resource; larger, more familiar ecosystems encompass more value components. For instance, valuing a tropical forest would include direct use (timber, ecotourism), indirect use (carbon storage, climate regulation), and non-use (existence value for the global public).

For soil biodiversity, the TEV is dominated by indirect use values, as core services like nutrient cycling, soil structure maintenance, and disease suppression are utilized indirectly but are fundamental to ecosystem function. It also provides direct use value, notably through genetic information used by pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries to develop products like antibiotics. Conversely, non-use value for soil biota is often limited because it lacks charismatic flagship species, making public attribution of existence value more difficult compared to iconic mammals or forests. This invisibility further compounds the challenge of generating political and financial support for its conservation.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 106;