Soil Microorganisms in Biotechnology: From Industrial Applications to Bioremediation

Virtually all groups of soil microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, algae, and protozoa, hold immense potential for diverse environmental, commercial, and industrial applications, much of which remains untapped. Their inherent ability to break down substrates and transform materials into new substances is a valuable resource for pharmaceuticals, food processing, chemicals, and mining. The intentional exploitation of microbes to generate useful products or desired environmental changes defines biotechnology. In a broader sense, biotechnology also serves as a crucial tool for acquiring fundamental scientific knowledge in genetics, metabolism, and whole-organism systems.

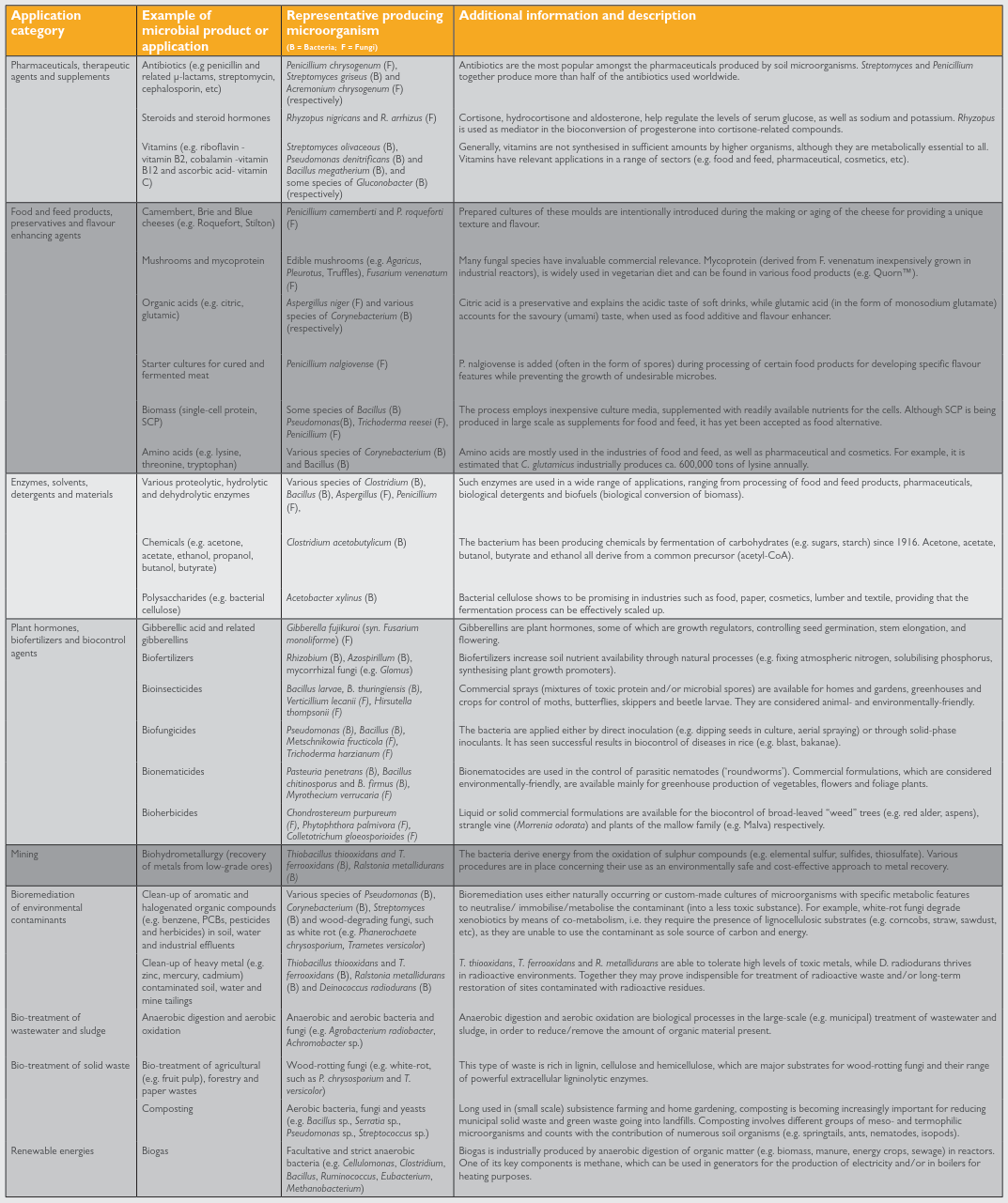

Microbial biodiversity is the foundational engine of biotechnology. The vast array of microbial characteristics translates into a swarm of metabolic features, enabling countless applications and products (see Table 4.4). Although the term is modern, the concept is ancient, exemplified by bread leavening, beer brewing, food fermentation (Fig. 4.17), and historical practices in animal and plant breeding. The Industrial Revolution enabled large-scale fermentation, marking the dawn of modern biotechnology (Fig. 4.19).

Table 4.4: A selection of biotechnologies which rely on soil organisms, including examples of species used

Fig. 4.17: Cheese making is one form of biotechnology which has existed for thousands of years

Fig. 4.19: An industrial scale fermentation unit

The field has expanded spectacularly with advances in molecular biology and recombinant DNA technology, which involves creating novel DNA combinations. Microbial cells can be engineered by transferring specific genes within or between species, a process that occurs naturally in the environment and challenges traditional species definitions. Microbial genetic engineering aims to create tailor-made "super" strains with enhanced biochemical features, thereby extending the utility of natural biodiversity.

Microorganisms are indispensable for life. Microbial cells themselves serve as nutrients, immunizing agents, or clean-up tools, while their enzymes and synthesized compounds are invaluable. Identifying useful strains begins with an intelligent microbial screening program, sourcing organisms from culture collections or environmental samples like soil. Selected microbes are cultured in bioreactors, often as immobilized cells on supports like diatomaceous earth, with tightly controlled parameters such as aeration, pH, and temperature.

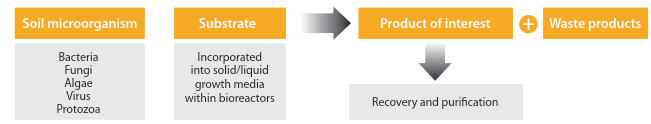

For metabolite production, the target compound must be isolated and purified from the growth medium (Figure 4.18). Commercial feasibility requires scaling up to industrial production, a complex process dependent on the microorganism and product. Ideal industrial strains exhibit high growth rates, abundant product yield, non-pathogenicity, and ease of culture in inexpensive media. The product, in turn, must be easily isolated with cost-effective recovery and purification steps.

Fig. 4.18: Typical steps in microbial-based industrial production of relevant compounds

Bioremediation leverages the natural degradative abilities of soil biota, primarily heterotrophic decomposers, to return contaminated environments to a pristine state. While plants and animals can be used, microorganisms are preferred due to their versatile metabolism. However, its success depends on the pollutant type, soil properties, and climate, underscoring that pollution prevention is always superior to remediation.

Different decomposers specialize in degrading specific compounds. Readily degradable substances like carbohydrates are attacked by many microbial groups, while recalcitrant compounds like lignin, cellulose, and hemicelluloses require specialists such as white rot fungi. Interestingly, many man-made pollutants like hydrocarbons structurally resemble lignin, allowing certain fungi to degrade them in contaminated soil. Selecting the right microbes is critical for effective contaminant metabolism and removal.

Bioremediation is implemented in three primary forms:

- Intrinsic Bioremediation: A natural process performed by native microorganisms without human intervention.

- Biostimulation: Enhancing the activity of indigenous microbes by adding nutrients or oxygen to the contaminated site.

- Bioaugmentation: Introducing specific microorganisms to a site to degrade contaminants that native populations cannot process.

Fig. 4.21: These three images show an example of bioaugmentation / bioremediation of a crude oil spill by combined strains of the soil fungi Trametes versicolor and Pleurotus ostreatus (better known as the edible oyster mushroom):

(a) shows the oil spill on day 1. Due to the porous nature of soil it would not be possible to remove the oil spill without removing a large amount of soil which would then have to be treated as contaminated waste. Due to the toxic nature of crude oil it is very unlikely that any plants could grow here with the soil in this condition.

(b) shows the oil spill on day 14 after inoculation with the combined strains of Trametes versicolor and Pleurotus ostreatus. The fungal hyphae are so abundant growing on the oil spill that they are clearly visible as the white on the soil. Already, after just 2 weeks the oil is greatly reduced.

(c) shows the same area of soil after 49 days. The original patch of soil is all but gone, along with the fungi, neither strain of which is now readily apparent. Some small patches of oil are visible at the edges, but further application of the fungi to these areas will remove them

Bioremediation has proven highly effective. In one documented case in Canada, approximately 38,000 m³ of soil contaminated with oil-tar byproducts was treated with a bacterial and nutrient mix (biostimulation and bioaugmentation). Within 70-90 days, organic pollutants were reduced by 40-90%, with heavy metals becoming immobilized within microbial communities. Further evidence of hydrocarbon bioremediation efficacy is illustrated in Fig. 4.21.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 113;