Economic Valuation Methods for Ecosystem Services: Approaches, Landmark Studies, and Critiques

Economists employ two broad methodological categories to value non-market environmental benefits: Direct (Stated Preference) and Indirect (Revealed Preference) approaches. Direct methods, such as contingent valuation, elicit values through surveys or experiments, asking respondents to state their Willingness to Pay (WTP) or Willingness to Accept (WTA) compensation for changes in environmental quality. A key advantage is their theoretical capacity to capture non-use values, though they also measure use values. Their primary drawback is their hypothetical nature, which can introduce significant biases, such as strategic misrepresentation or hypothetical bias, stemming from reliance on subjective responses rather than observed behavior.

Conversely, Indirect (Revealed Preference) methods infer values by observing actual market behavior linked to environmental goods. They rely on the concept of weak complementarity, where the value of a non-market good is revealed through its influence on a related marketed commodity. For example, the hedonic pricing method analyzes how air quality affects property values, while the travel cost method uses expenditures on trips to deduce the recreational value of a natural site. In agriculture, the cost of lost income from reduced yields can quantify the economic damage of soil degradation. The suitability of each technique depends on data availability, policy context, and the specific type of value being measured, with no single method being flawless.

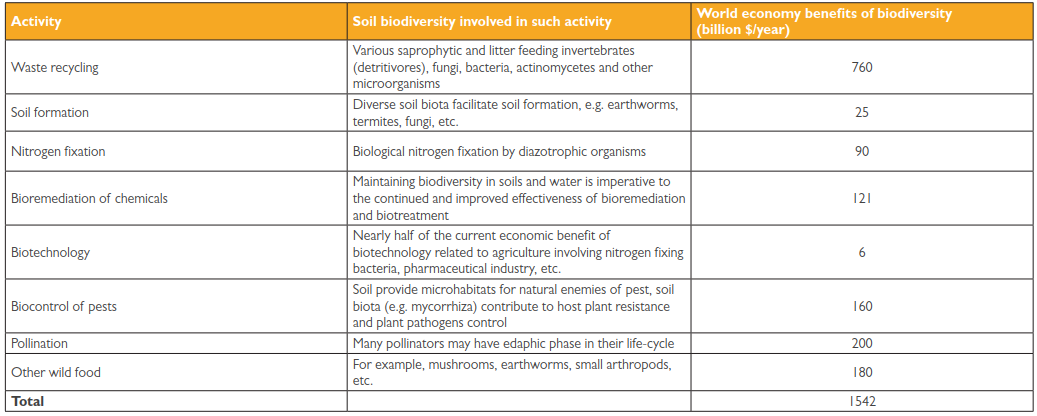

Landmark studies have attempted to quantify the immense value of global ecosystem services. The seminal 1997 study by Costanza et al., published in Nature, estimated a minimum annual value of US$33 trillion for the world's ecosystem services—a figure surpassing half the global GDP at the time. Similarly, Pimentel et al.'s 1997 study, "Economic and Environmental Benefits of Biodiversity" (Table 4.5), focused on terrestrial ecosystems, valuing biodiversity's annual global economic contribution at nearly US$3 trillion, with roughly half ($1.5 trillion) attributed to soil organisms. The significant discrepancy between these figures, partly due to different scopes, underscores the inherent difficulty and necessary assumptions in monetizing ecosystem services.

Table 4.5: Proposed economic value of various ecosystem services provided by the soil biota

These studies have sparked intense debate and fundamental criticism from economists. A core critique is the confusion of marginal and total values. Economic value is properly derived from estimating the benefit of a marginal (incremental) change in provision. Placing a finite price on entire, life-sustaining systems like global ecosystems eschews this principle, as their total value to human existence is essentially infinite. By providing headline "ballpark figures," however, this work played a crucial role in raising the profile of biodiversity and ecosystem services among policymakers by framing them in accessible monetary terms.

Another widespread methodological shortcoming, especially in global-scale studies, is the extensive and often arbitrary use of benefits transfer. This technique applies value estimates from one specific location and ecosystem to superficially similar sites worldwide, extrapolating on a per-hectare basis. This can introduce significant error by ignoring critical local ecological, economic, and social heterogeneity. These criticisms clarify that the Total Economic Value (TEV) of biodiversity is not an index of overall performance but a tool to assess the economy-wide consequences of incremental changes in its provision.

Consequently, while numerous studies value specific environmental goods, far fewer address the economic benefits of biodiversity per se. Most research focuses on valuing biological resources or their habitats rather than diversity itself. Early attempts used a diversity function based on pairwise genetic distances between species, implicitly assuming diversity is desirable without establishing a causal mechanism linking genetic distance to economic usefulness. Modern environmental economics increasingly treats biodiversity as a commodity or insurance asset, focusing on its role in stabilizing ecosystem function and providing resilience, thereby offering a more tractable pathway for valuation and policy integration. A comprehensive analysis of these valuation issues is presented in Chapter 5 of the TEEB D0 report, "Ecological and Economic Foundations" (see http://www.teebweb.org).

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 136;