Biological Weathering: How Soil Organisms Break Down Rocks and Build Ecosystems

Defining Weathering and the Biological Contribution. A critical function of the soil biota is the weathering of rock, the process of breaking down and altering rocks and sediments at the Earth's surface through biological, chemical, and physical agents. Classical examples include the physical disintegration of rocks by freezing water and chemical dissolution by acidic rainwater. Historically, biological weathering was viewed as indirect, where organisms merely enhanced physical and chemical processes, such as by creating moist microenvironments or releasing acids. However, modern research has revealed that microorganisms engage in remarkable direct weathering, actively liberating essential nutrients. Furthermore, fungi are now known to play a pivotal role in the neoformation of minerals, showcasing their ability to both break down and create soil components.

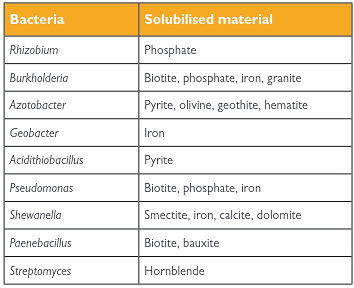

Mechanisms of Microbial Rock Weathering. Bacteria, fungi, and lichens are now recognized as primary agents of rock weathering, acting as direct producers and liberators of minerals through a variety of sophisticated mechanisms (Table 4.2). These microbes primarily weather rocks via redox reactions and the production of organic acids and chelates that dissolve mineral structures. The released elements then become vital nutrients for plants, forming the foundation of the soil food web. Fungi, being more mobile than bacteria, employ additional strategies. Their hyphae can exert immense physical force; the osmotic pressure produced by fungal appressoria can reach 10-20 pN/µm², enough to penetrate bullet-proof material, allowing them to physically breach mineral surfaces.

Table 4.2: Selected examples of bacteria solubilising minerals

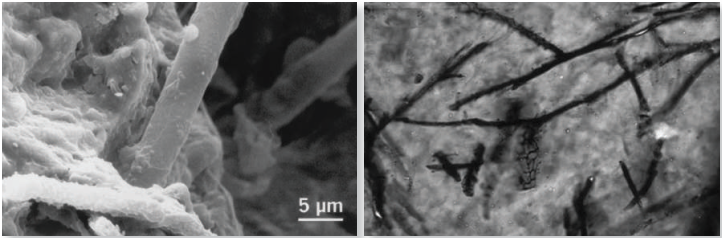

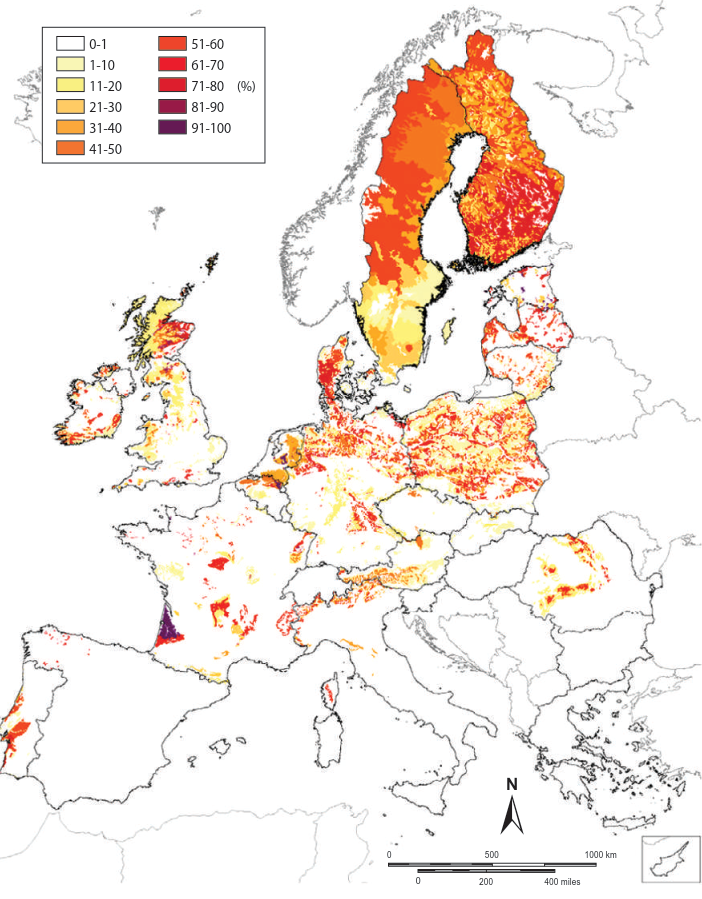

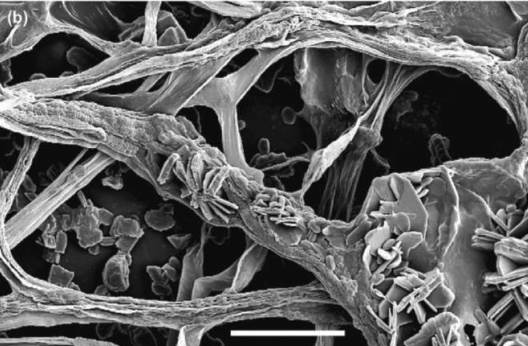

Fungal Tunneling and Mineral Liberation. The weathering power of fungal hyphae is visually striking, as seen in the bioweathering of feldspar, a common mineral in granite (Figure 4.4). A key process is mineral tunneling, where hyphae form intricate tunnels inside mineral particles. This phenomenon has been extensively observed in feldspar within the E horizons of Podzols, which are widely distributed across Europe (Fig. 4.5). The mechanism is believed to involve mineral dissolution by anions exuded specifically at the tips of mycorrhizal hyphae. Over time, the growing hyphae form permanent tunnels or surface grooves, directly releasing calcium (Ca) and potassium (K) into the ecosystem, a crucial ecosystem service that enhances soil fertility beyond the immediate location.

Fig. 4.4: Rock-eating mycorrhiza. Left; Scanning electon micrograph showing two fungal hyphae penetrating a feldspar grain: (EHd) Right; Thin section micrograph of a feldspar grain from a Podzol E horizon, criss-crossed by tunnels of about 5μm in diameter; The feldspar grain originates from the E horizon of a 5400-year-old sand dune along Lake Michigan

Fig. 4.5: Distribution of Podzols in the European Union

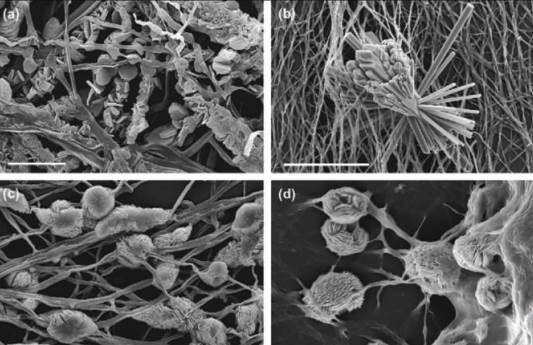

Neoformation: How Organisms Create New Minerals. Beyond destruction, soil biota are also builders. Secondary mineral formation has been documented in free-living and symbiotic fungi. For instance, lichens and mycorrhizal fungi form metal oxalates, iron (hydr)oxides, and clay minerals. Carbonates have also been found to be formed by these organisms. The crystalline material nucleates and deposits onto and within the fungal cell walls (Figure 4.7). A prime example is calcium oxalate (Fig. 4.8), the most common oxalate in soils, whose formation by fungi creates a calcium reservoir and influences phosphate availability. This feedback between the soil biota and the mineral component is a fundamental governor of nutrient availability and overall soil fertility.

Fig. 4.7: Mycogenic oxalates. (a) Magnesium oxalate and hydromagnesite precipitated on Penicillium simplicissimum; (b) strontium oxalate hydrate on Serpula himantioides; (c) calcium oxalate monohydrate and calcium oxalate dihydrate on S. himantioides; and (d) copper oxalate hydrate precipitation on Beauveria caledonica. Bars (a) 20 μm; (b) 100 μm; (c,d) 20 μm

Fig. 4.8: Calcite and calcium oxalate monohydrate precipitated on Serpula himantioides. Bars (b) 10 μm

Weathering in the Context of Soil Formation and Sustainability. Weathering is an indispensable and slow process of soil formation. In many global ecosystems, particularly agricultural lands, erosion rates currently outpace soil formation, leading to a net loss of this vital resource. The role of biodiversity in this process is profound. Early colonizers like lichens fix atmospheric carbon, creating initial organic matter that supports other organisms. As the system develops, plant roots grow into rock cracks, accelerating weathering. This establishes a positive feedback cycle: weathering releases essential elements that fuel the soil biota, which in turn increases weathering rates. Even earthworms accelerate weathering, with evidence showing they transform the clay mineral smectite into illite. Ultimately, the level of soil biodiversity directly influences both the rate of soil formation and its final characteristics, highlighting the critical link between a thriving biological community and a sustainable planet.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 158;