Extreme Soil Environments: Definition, Ecosystems, and Microbial Adaptations

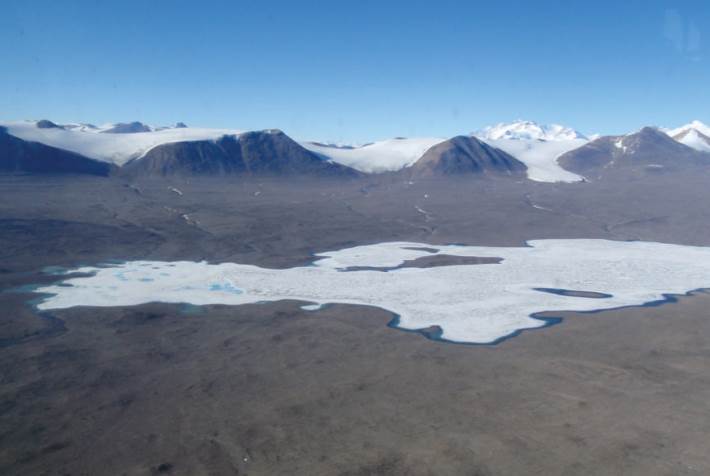

An Introduction to Extreme Terrestrial Ecosystems. A diverse array of terrestrial soil environments can be classified as extreme, ranging from deep subterranean caves to the vast expanses of cold and hot deserts (Fig. 3.38 and 3.39), and extending to the highest mountain peaks. These ecosystems, once believed to be largely sterile, are now recognized as hosting numerous organisms that have developed specialized physiological adaptations for survival. These life forms perform critical ecosystem functions, such as biogeochemical cycling, which are essential for nutrient turnover even under harsh conditions. Although the food webs in these environments are often simplified and support fewer species, their unique evolutionary paths contribute valuable genetic diversity to the global pool. Consequently, scientists view these extremophiles as a significant resource for bioprospecting, with potential applications in commercial, medical, and industrial sectors.

Fig. 3.38: Lake Fryxell, in the cold desert of Taylor Valley, McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica

Fig. 3.39: The Chihuahuan Desert, a hot desert near Orla, Texas

The scientific value of these habitats extends far beyond bioprospecting. Extreme environments serve as natural laboratories for studying the evolution of life on Earth and the potential for life on other planets. In ecology, they are crucial for elucidating the specific roles species play in maintaining ecosystem function under stress. However, our understanding of the organisms and communities within these environments remains limited, creating a pressing need to acquire more information on their vulnerability to global changes, such as climate and land use change. This urgency is compounded by research indicating that the loss of a single species can have a disproportionately large impact on ecosystem processes in inherently low-diversity systems like extreme soils. Therefore, it is critical to identify the resident species, determine their functional roles, and assess their distribution across similar habitats.

Defining Extreme Environments and Their Inhabitants. Life persists across nearly all environments on Earth, with some organisms not just surviving but thriving in conditions that appear harsh and uninhabitable to humans. The range of extreme environments is vast, encompassing frigid habitats like cryoconite holes in glaciers and permafrost soils, to scorching hot habitats like desert surfaces that can exceed 50°C. Each of these environments presents significant physiological challenges that life forms must overcome. Organisms that have adapted their growth and survival strategies to these conditions, for whom the severe environment is the norm, are collectively known as extremophiles, a term literally meaning ‘lovers of the extreme’.

Other organisms are not true lovers of the extremes but rather tolerators; they can survive periods of extreme temperature or moisture on a seasonal or daily basis but do not grow or reproduce during these stressful intervals. Such fluctuating environmental conditions can be exceptionally difficult for biota to cope with, forcing them to evolve specific survival strategies or resilient life stages. For the purpose of clarity, this text defines an extreme environment as any unmanaged terrestrial habitat where conditions exist—such as temperature, moisture, or pressure—that fall beyond the range in which most organisms grow optimally. While extreme temperatures and low water availability are primary stress factors, other variables like pH, salt concentration, osmotic pressure, and radiation also critically influence microbial growth and survival.

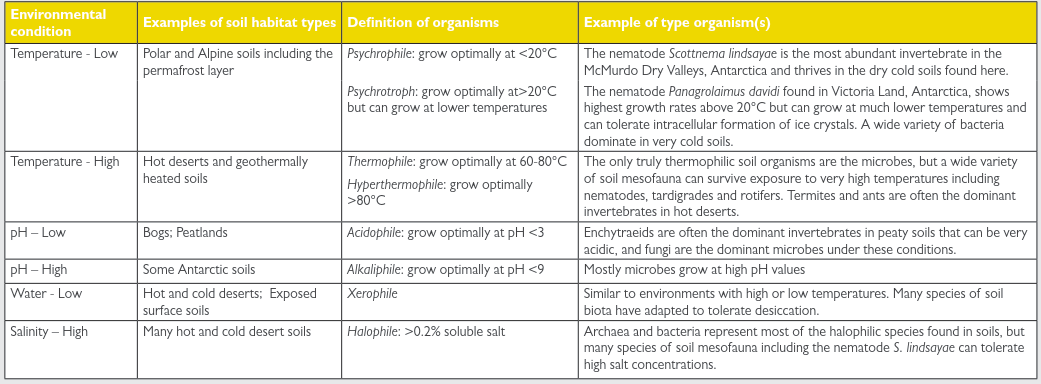

Characteristics of Extreme Soil Ecosystems. Numerous types of extreme soil ecosystems exist where soil organisms routinely encounter the abiotic factors previously described. The most prominent extreme conditions in soils include severe temperatures, low water availability, high and low pH values, and high salt concentrations (see Table 3.3). It is important to note that in most extreme soil environments, there is generally a high degree of spatial and temporal variation in these stress factors, which often act in concert to influence microbial growth and community structure. These locally extreme conditions are frequently reflected in the area's topography, geology, climate patterns, and vegetation cover, creating a complex mosaic of microhabitats.

Table 3.3: Some examples of extreme conditions experienced by soil organisms, where such conditions occur and the organisms that are common in these extreme soils

Deserts provide a quintessential example of an extreme soil environment, defined primarily by a profound lack of precipitation. They are generally classified as semi-arid (<600 mm precipitation year⁻¹), arid (<200 mm precipitation year⁻¹), or hyper-arid (<25 mm precipitation year⁻¹). Deserts are found not only in hot regions but also in coastal areas, high-altitude plateaus, and the Polar Regions. The most extreme desert soils are found in hyper-arid hot and cold deserts, where organisms must contend with both severe water scarcity and temperature extremes. Within these deserts, local weather patterns, topography, and sparse vegetation greatly influence the below-ground communities, resulting in considerable spatial and temporal heterogeneity. In general, the biodiversity of soil biota tends to decrease with the increasing severity of water limitation, and in the most extreme zones, the diversity is often limited to just a few, highly specialized groups of organisms.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 110;