Humus Forms: A Comprehensive Guide to Mull, Moder, and Mor as Ecosystem Indicators

Humus, the dark, partially decomposed organic matter at the soil surface, has long been recognized as the central seat of biological and physicochemical processes essential for soil development and ecosystem function. This concept is paramount in non-tilled soils where the topsoil remains undisturbed. The scientific foundation for classifying humus was laid in the late 19th century by Müller and later expanded by Kubiëna, who emphasized the interaction between soil animals, vegetation, geology, and climate. Today, humus forms are understood as key drivers of ecosystem processes, highlighting the need for a universal classification system to diagnose their characteristics and interpret their ecological significance.

Terrestrial ecosystems manifest three primary humus forms, each representing a distinct biological "strategy" for nutrient cycling (Fig. 2.16). Mull is characterized by an intense mixing of organic and mineral matter, largely facilitated by earthworm activity, resulting in a crumbly, nutrient-rich organo-mineral horizon. Moder features a slower transformation of litter by fungi and litter-dwelling animals, leading to a visible accumulation of organic humus near the surface. Mor is defined by the very slow decomposition and accumulation of undecayed plant debris, with a sharp, abrupt transition to the underlying mineral soil.

Fig. 2.16: The five main type of terrestrial humus forms which prevail in temperate ecosystems (bar = 10 cm)

These humus forms represent a gradient of decreasing biological activity and nutrient availability, directly correlating with ecosystem productivity and biodiversity. Mull supports the highest biodiversity and fastest nutrient cycling, typically found on base-rich parent rock under mesic climates. This environment fosters rapid plant growth, which in turn produces nutrient-rich, lignin-poor litter. This high-quality litter favors rapid bacterial decomposition and earthworm activity, creating a positive feedback loop that sustains productive, multi-layered forests.

Conversely, the Mor humus form signifies a more conservative, nutrient-poor ecosystem with lower species diversity and slower nutrient turnover. Using Aesop's fable as an analogy, Mull is the "waster" (the cicada), rapidly cycling resources, while Mor is the "hoarder" (the ant), storing organic matter. Each form represents the most efficient resource-use strategy for its specific environmental constraints, making humus forms powerful indicators of local site quality, geology, and climate.

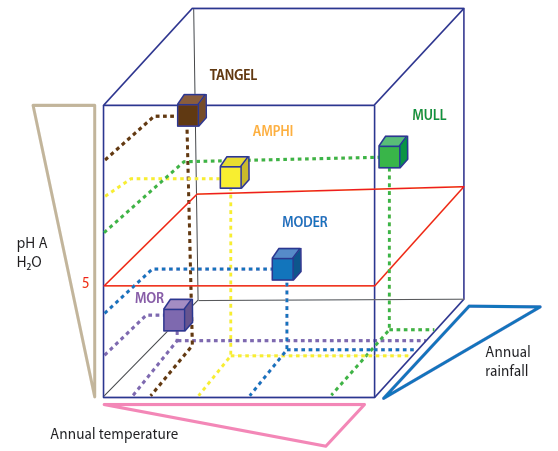

Driven by the need for a standardized system, European researchers formed the Humus Group in 2003. This collaborative network has worked to harmonize concepts, leading to the identification of new forms like Amphi and the re-description of others, such as Tangel (Fig. 2.16). A key conceptual model that has emerged positions Mull as the central attractor for forest humus forms, with Moder and Mor representing deviations under harsher environmental conditions, such as colder temperatures or poorer geology.

The complexity of humus systems is illustrated by forms like Amphi, which exhibits characteristics of both Mull and Moder. This duality results from strong seasonal biological activity fluctuations in Alpine and Mediterranean environments on calcareous substrates. In contrast, Tangel forms at high elevations on hard limestone, where litter remains largely undecomposed for most of the year because invertebrates cannot burrow into the parent rock, and decomposer activity is severely limited by climate.

The classification of humus forms has been refined into a detailed, flexible system. Diagnostic horizons are labeled as OL (undecayed litter), OF (fragmented litter), OH (humified litter), and A (mineral matter mixed with organic matter). Prefixes like 'eu-' (normal) and 'dys-' (atypical) and suffixes like '-zo' (with faunal activity) or '-noz' (without faunal activity) allow for precise description. The size of aggregates from invertebrate feces is classified as micro-, meso-, or macro-, enabling experts to label a wide variety of profiles accurately.

Fig. 2.19: The five main terrestrial humus forms in a 3D frame of environmental conditions prevailing in Europe. Each axis represents the scale of different climatic variables. (JFP/GSa)

Beyond academic interest, the classification of humus forms serves as a critical diagnostic tool for ecosystem health. The Humus Index, which scales acid soil humus from Mull to Mor, has proven correlated with soil chemistry, forest stand properties, and floristic composition. Furthermore, specific humus forms are sensitive indicators of past and present climate conditions, making them valuable for modeling the effects of global climate change (Fig. 2.19). This underscores the need for expert tools and finer characterization to leverage humus forms in assessing ecosystem vitality and predicting future environmental trends.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 109;