Soil Microhabitats and Ecosystem Engineering: How Life Shapes the Pore Space

Unlike plants, which must exert significant suction to extract water from soil pores, microorganisms are far less restricted. They primarily move within the water films coating soil particles, rather than attempting to remove the water itself. The fact that water is so tightly bound within micropores actually guarantees its availability for the soil microbiota the vast majority of the time. This constant, if limited, access to water sustains microbial life except during periods of extreme drought, creating a relatively stable aquatic micro-environment.

During extreme drought, when even micropores may dry out, soil organisms employ various survival strategies. These generally involve entering a resistant state of dormancy with restricted or zero metabolism. In this state, organisms can appear lifeless, only to rapidly reactivate and "come back to life" once water becomes available again. This resilience highlights a key feedback mechanism within the soil ecosystem, where biological activity is directly pulsed by the physical availability of water and habitat space.

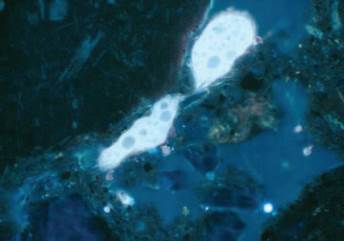

The life within the soil is predominantly confined to the three-dimensional pore network that forms its habitat. To navigate this labyrinth, organisms must be small and deformable enough to squeeze through the existing gaps between soil particles. Fig. 2.2 shows testate amoeba situated within these pore spaces, while Fig. 2.3 captures an amoeba deforming its body to traverse a narrow pore in search of bacterial prey. These amoeba are, in turn, preyed upon by larger organisms like nematodes, forming a complex food web entirely within the pore architecture.

Fig. 2.2: Testate amoeba located in the pore space of a soil

Fig. 2.3: An amoeba squeezing through the narrow pore of a soil

Fig. 2.4: Fungal hyphae enmeshing and bridging the gap between two soil aggregates

The scale of an organism determines its access and vulnerability within the pore matrix. Fig. 2.5 shows a nematode navigating the three-dimensional pore space. Nematodes are considerably larger and less deformable than amoeba. This size difference means amoeba can access micropores that are inaccessible to their predators. These small pores act as refugia, allowing prey species to avoid being eaten and contributing to the maintenance of high biodiversity by providing a safety mechanism within the soil habitat.

Fig. 2.5: A nematode curling though the pore space of a soil

The soil pore system is not a static environment; it is highly dynamic. The network constantly changes due to processes like shrinking and swelling during wetting and drying cycles, as well as freezing and thawing. As a result, sections of the pore network that were once disconnected can become linked as new cracks form, while previously connected pathways can be sealed off. This constant reconfiguration alters habitat connectivity and resource access for the entire soil biota on a continual basis.

Conversely, the soil biota actively modifies its own habitat, creating important feedback loops. Many organisms function to stabilize soil aggregates within the pore system. This can be achieved through the excretion of sticky, glue-like compounds or by the physical binding action of structures like fungal hyphae (Fig. 2.4). These biological stabilization effects have significant beneficial impacts, as they enhance soil structure, increase porosity, and help reduce soil erosion by making aggregates more resistant to wind and water.

Larger organisms, such as earthworms, act as powerful ecosystem engineers, capable of physically moving soil particles and creating their own macropores through a process known as bioturbation. The pores created by living organisms are specifically termed biopores. These biopores are generally much larger than other soil pores and become dominant pathways for the preferential flow of water, significantly speeding up water infiltration into the soil profile and reducing harmful surface runoff after rainfall events.

The classification of earthworms as ecosystem engineers is well-deserved, as their activities lead to large-scale changes in the soil environment. Beyond creating biopores, they mix soil layers and incorporate organic matter as they move through the vertical profile. This engineering fundamentally alters the physical and chemical properties of the soil, creating new habitats for other organisms and enhancing overall ecosystem function. Their actions are a prime example of how biology shapes its physical environment.

Biopores are also created by other organisms, most notably by plant roots. Roots possess significant penetrating power, able to force soil aggregates apart as they grow. When the plant dies and the root decays, the tubular void it created persists as a lasting legacy in the soil structure. This remnant biopore continues to function as a channel for preferential water flow and serves as a readily navigable pathway for other organisms, including new roots, to move through the soil, effectively reducing the energy required for subsurface exploration.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 93;