Soil Biodiversity: Defining the Complex World Beneath Our Feet

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment provides a comprehensive definition of biodiversity, describing it as the variety of living organisms across all ecosystems, including terrestrial, marine, and aquatic environments, and the ecological complexes they form. This encompasses diversity within species, between species, and of entire ecosystems. For the scope of this text, the focus is specifically on soil biodiversity, which refers to the vast array of living organisms inhabiting the soil matrix. This specialized concentration allows for a detailed exploration of one of Earth's most critical and diverse habitats.

A closely related and more specific term is soil biota, which denotes the complete community of living entities within a given soil system. For instance, one can state that the soil biota in a grassland is generally more diverse than in an arable farming system. This is synonymous with stating that grassland soils possess higher levels of soil biodiversity. Both formulations accurately convey the same scientific concept, emphasizing the richness of life forms in different soil environments. Understanding this terminology is fundamental to discussing the components and functions of the soil ecosystem.

The soil system itself is a model of extreme complexity, exhibiting significant variation both spatially and temporally. Its composition consists of a mineral fraction, primarily composed of silica and a mixture of trace metals, and an organic matter portion, which contains a vast suite of different organic compounds. This matrix also houses an immense diversity of organisms and, in all but the driest conditions, a water component. This intricate combination of elements creates a dynamic and challenging environment for life.

Furthermore, soils exist across a spectrum of textures, defined by the varying proportions of sand, silt, and clay particles. This texture influences the soil's structure, creating a network of pores ranging from large spaces that can be dry to micropores that are almost permanently water-filled, barring extreme drought. The concentration of organic matter is not uniform, typically decreasing with depth and varying across different spatial locations within the same soil profile. This heterogeneity is a key driver of biological diversity.

This high degree of environmental variability means soil contains an immense number of distinct ecological niches. These niches have, through evolutionary processes, given rise to a staggering array of biodiversity (Fig. 1.2). When employing a taxonomic approach to measure biodiversity, it is often noted that tropical rainforests host more than half of the world's estimated 10 million species. However, applying this same approach to soil reveals a concentration of life that is equally astounding, with hundreds of thousands to potentially millions of species inhabiting a single handful of forest soil, rivaling the diversity of some of the world's most vibrant ecosystems.

Fig. 1.2: This highly simplified figure aims to give some idea of the distribution of organisms vertically through the soil profile. It is clearly an oversimplification and in fact microorganisms such as bacteria (c) and protozoa (e) are distributed throughout the soil profile, although with the highest biomass being found near the soil surface which is richer in organic matter. The two collembolans are adapted for living at different soil depths with the species shown in (a) being more adapted for living on or near the soil surface and that shown in (b) being more adapted to living at deeper levels. These differences are discussed in more detail in Section IX.

Earthworms are also found in greater numbers closer to the soil surface but can also be found down to depths of 1 metre or more and form three different ecological groups which are discussed in more detail in Section XIII. Fungi are also found throughout the soil profile but are particularly common close to the soil surface where there is higher concentrations of organic matter as well as numerous plant roots with which they can form symbiotic relationships (f). This figure only shows a very few selected organisms. Many more organism groups make the soil their home as this atlas will make clear

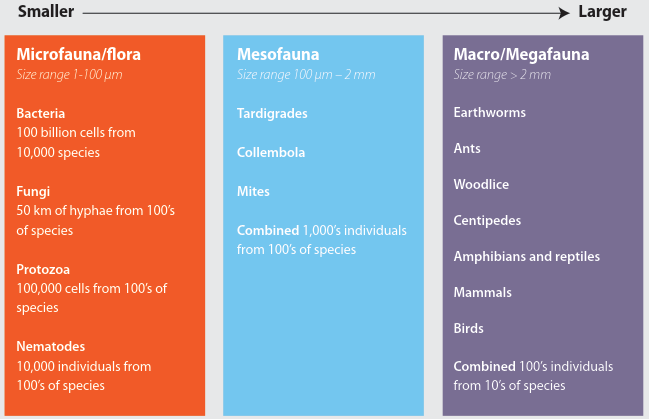

Beyond its incredible diversity, the soil environment also supports astonishingly high levels of organism abundance. The specific levels of both abundance and diversity fluctuate from one soil to another, influenced by critical factors such as organic matter content, soil texture, pH, and human soil management practices. The table below provides an approximate breakdown of the number and diversity of organisms, categorized by size, typically found in one square metre of temperate grassland soil, illustrating the density of life beneath our feet.

Table 1.1: Functional Grouping of Soil Biota by Size

In addition to size-based grouping, some soil biologists classify the soil biota using the metric of effective body width. This method categorizes organisms based on their ability to move through different soil pore sizes, which is a more functional approach to understanding their ecological roles. While the methodology differs, the resulting cutoff points between groups are generally similar, and there is broad scientific consensus on which organisms belong to each respective category, whether defined by size or mobility.

In biological terms, an organism is any contiguous living system, such as an animal, plant, fungus, or microorganism. All organisms, in their most basic form, are capable of responding to stimuli, reproduction, growth, and development while maintaining homeostasis. This fundamental definition applies to all members of the soil biota, from the smallest microbe to the largest earthworm, unifying the community through shared biological processes.

Organisms may be unicellular, consisting of a single cell like most bacteria, or multicellular, composed of many trillions of cells organized into specialized tissues and organs. The term multicellular describes any organism made up of more than one cell, encompassing the vast majority of the meso- and macrobiota. This cellular complexity allows for the specialization of functions that are essential for nutrient cycling, soil structure formation, and the overall health of the ecosystem they inhabit.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 101;