Soil Fungi: Ecological Roles, Mycorrhizal Relationships, and Environmental Significance

Fungi are commonly recognized by their mushrooms, yet these structures merely represent the fruiting bodies of one subset within an immensely diverse biological kingdom. Occupying a distinct taxonomic kingdom separate from prokaryotes, plants, and animals, fungi are ubiquitous in all soils. They often constitute the majority of the below-ground biomass, particularly in soils rich in organic matter. Their functions are critical to the health and operation of soil ecosystems, encompassing a vast array of biological and biochemical roles.

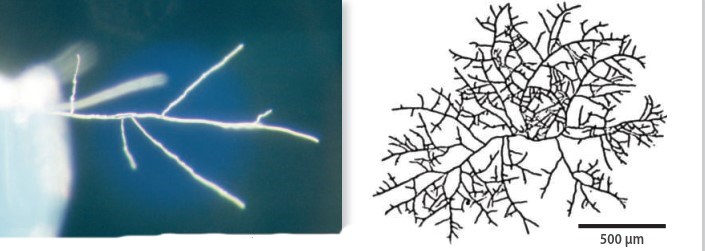

Fungi exhibit two fundamental growth forms: a single-celled yeast-like form and the far more prevalent filamentous structure known as a hypha. These thread-like hyphae grow via tip extension and undergo branching to form an extensive network called a mycelium (Fig. III.I). This mycelial growth form is exceptionally well-adapted to the soil matrix, enabling fungi to navigate the three-dimensional pore network in search of nutrients. Furthermore, hyphae can aggregate and differentiate into diverse structures, including long-range foraging cords, microscopic spore-bearing organs, complex mushrooms, and specialized nematode-trapping devices (Figure III.IIIf).

Fig. III.I: Diagram showing fungal hyphae at different scales with hyphae branching on the left and the larger mycelium formed by hyphae over time on the right.

Fig. III.III: A selection of photographs of different fungi showing a range of diverse structures. (a) shows a thin section viewed down a microscope with fungal hyphae (stained blue) growing through the pore space of a soil; (b) shows a puff ball, the fruiting body Calvatia gigantea which is full of spores which are dispersed over a wide area when the puff ball bursts; (c) the fruting bodies of Pilobilus sp., which actually produces the fastest acceleration rates in the living world; faster than a missile or a speeding bullet! The black ends are spores which can be shot up to two metres due to the fluid sacks behind each spore filling slowly with fluid until they burst, dispersing the spores; (d) the fruiting body of Amanita muscari, the classic ‘toadstool’ seen in fairytale drawings; (e) the fruiting body of Lacrymaria sp. (f) the carnivorous fungi Drechslerella anchonia which captures nematodes in rings which grow along its hyphae then penetrates the skin and consumes the nematode from the inside out (g) the fruiting body of Hygrocybe punicea

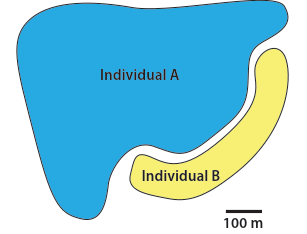

Although classified as microbes, some fungal mycelia achieve colossal dimensions, representing arguably the largest single organisms on Earth. Documented cases exist of individual Armillaria bulbosa mycelia spanning several kilometres and weighing hundreds of tonnes (Fig. III.II; see also Section 3.1). This species, common in American hardwood forests, exemplifies this scale, with one individual reported covering over 890 hectares. Armillaria is also present in European and Japanese forests, playing a vital ecosystem role by decomposing dead wood.

Fig. III.II: The variable sizes of mycelium of two individuals of fungal species Armillaria bulbosa

The relationship between soil fungi and trees is often symbiotic and essential. Many tree species require a mutually beneficial association with soil-based fungi, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), for successful growth. However, threats including invasive species, landfill, and air pollution are driving a decline of AMF in European and North American forests. A potential mass extinction of these soil fungi would severely jeopardize forest ecosystem health and survival. Systematic records of mushroom diversity in Europe show a sharp decline, underscored by initiatives like Switzerland's first fungal 'Red List', detailing 937 species at risk of extinction.

A primary function of soil fungi is nutrient cycling, where they act as primary decomposers. They secrete a broad spectrum of enzymes capable of degrading resilient plant materials like cellulose and lignin, thereby releasing nutrients for plant and microbial uptake. Certain fungi solubilize phosphorus or mobilize iron through organic acid excretion, while interconnected mycelial networks facilitate rapid nutrient transport across soil regions, surpassing simple diffusion rates.

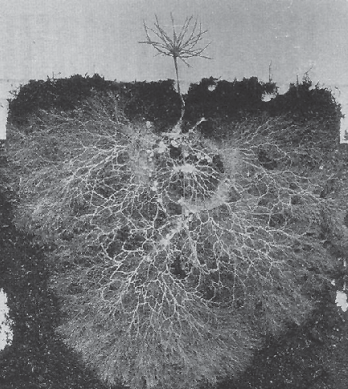

Biological interactions are central to fungal ecology. Mutualistic associations between plant roots and fungi, termed mycorrhizae, are exceedingly common (Fig. III.IV). In this symbiosis, the fungus receives carbon from the host plant and, in return, enhances the plant's access to soil nutrients like phosphorus.

Fig. III.IV: In the above image the fungal mycelium which forms the mycorrhizal association with the plant roots are clearly visible. The white growth is almost all fungi and not plant roots as it may first appear

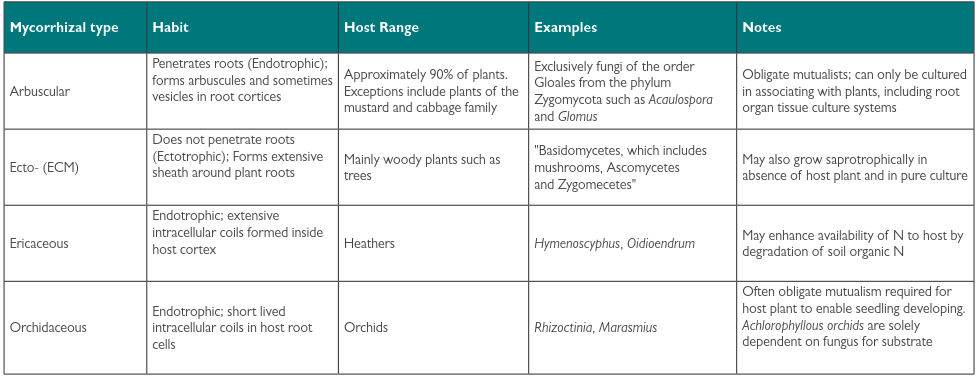

These associations vary, differing in host range and fungal colonization patterns (Table III.I). Conversely, many soil fungi are pathogenic, causing diseases such as 'take-all' of cereals (Gaeumannomyces graminis) or root rots from Rhizoctonia solani, leading to significant agricultural losses. Fascinating insect-fungus relationships also exist, including ants that cultivate specific fungi within their nests as a regulated food source.

Table III.I: The basic characteristics of the four mycorrhizal types. Taken from Ritz (2005)

Soil fungi profoundly influence soil structure through multiple mechanisms. As hyphae grow, they bind soil particles, and dense mycelia can physically enmesh the soil fabric (Fig. III.V). Fungal exudates include adhesive compounds that glue particles together and water-repellent substances that can stabilize soil. However, this hydrophobicity may also impede water infiltration, presenting a potential management challenge.

Fig. III.V: Fungal hyphae enmeshing two soil aggregates and bridging the pore space in between. Fungi have been shown to be important in reducing the risk of erosion through this mechanism, as well as others

Fig. III.VI: A sliced open Perigord truffle. Prices of these truffles can exceed 3000 Euros per kilo

Humanity exploits soil fungi for diverse biotechnological applications. Edible fungi range from the highly prized Perigord truffle (Tuber melanosporum; Fig. III.VI), a mycorrhizal associate of oaks, to the mass-produced mycoprotein from Fusarium venenatum, used in meat alternatives. Industrially, fungi are harnessed for producing organic acids, polysaccharides, antibiotics, and agrochemicals. Furthermore, fungi antagonistic to pests and weeds are successfully deployed as biocontrol agents, reducing reliance on synthetic chemicals in agriculture and horticulture.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 164;