Soil Prokaryotes: Bacteria and Archaea in Terrestrial Ecosystems

Definition and Classification. The term Prokaryote encompasses all unicellular organisms that lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Their genetic material is not enclosed within a clearly defined nuclear envelope. This group constitutes two of the three fundamental Domains of Life: Bacteria and Archaea. Both domains are abundant in soil environments, with bacteria typically representing the more numerous and diverse group in most terrestrial systems. Historically, Archaea were believed to reside exclusively in extreme habitats, but they are now recognized as ubiquitous soil inhabitants, though their specific roles are less understood than those of bacteria.

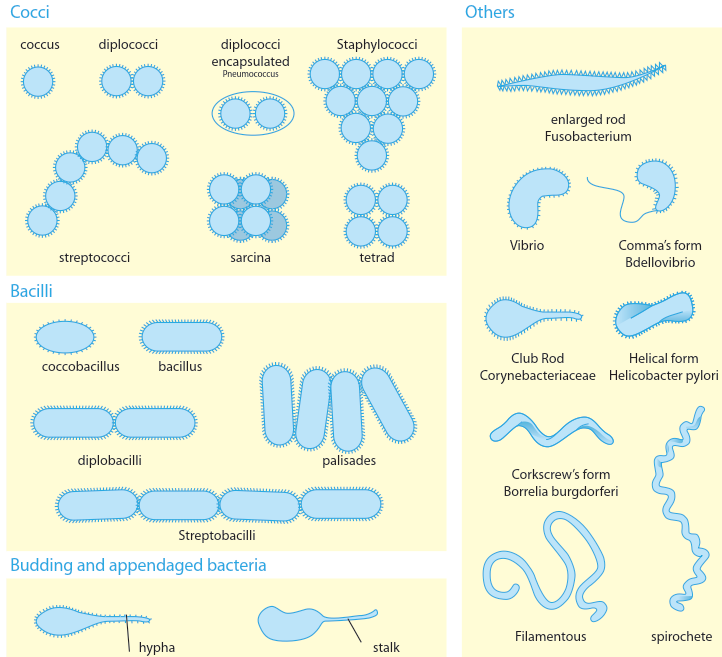

Abundance and Distribution in Soil. Prokaryotes exhibit a distinct vertical distribution within the soil profile. Their populations are highest near the surface, closely associated with organic matter and the rhizosphere—the soil zone influenced by plant roots. This abundance declines markedly with increasing depth due to reduced nutrient and oxygen availability. As microscopic entities, prokaryotes are invisible to the naked eye and require microscopy for observation. Their morphological identification is challenging, as they are categorized into a relatively small number of groups based on cell shape and colonial growth patterns in culture (see Fig. I.I).

Fig. I.I: The different shapes of prokaryotic cells that can be seen under a microscope

Research Challenges and Taxonomic Complexity. Studying soil prokaryotes is complicated by a significant obstacle: an estimated >90% of soil bacteria resist cultivation under standard laboratory conditions. Consequently, research increasingly relies on molecular genetic techniques. A further complication in prokaryotic taxonomy is the lack of a clear consensus on defining a bacterial species. Bacteria frequently engage in horizontal gene transfer, swapping genetic material between cells or acquiring it from the environment, blurring traditional species boundaries.

Functional Roles and Symbioses. Despite morphological simplicity, prokaryotes are incredibly diverse functionally. They engage in numerous critical processes, including forming vital symbiotic relationships. Lichens, for example, are symbiotic associations between fungi and photosynthetic partners, often cyanobacteria. Some of the most ecologically significant symbioses drive global biogeochemical cycles, such as the nitrogen cycle. Bacteria like Rhizobium (forming nodules on legumes; Fig. I.III) and actinomycetes from the genus Frankia (nodulating tree roots; Fig. I.II) convert atmospheric nitrogen into plant-usable forms, directly enhancing soil fertility.

Fig. I.II: Actinomycetes are a type of bacteria from the phylum Actinobacteria. The genus Frankia is capable of fixing nitrogen and does so by forming root nodules with actinorhizal plants, including many species of tree. The above image shows a cross section though a root nodule taken from the root of an Alder

Fig. I.III: Root nodules formed by Rhizobium sp. on the roots of a leguminous plant as part of a symbiotic relationship between the bacterium and the plant. The plant provides a safe environment, rich in sugars as food for the bacterium which in turn fixes nitrogen into plant usable forms

Pathogenic Prokaryotes. Not all prokaryotic impacts are beneficial. Many species are pathogenic, causing diseases in plants, animals, and humans. Notorious soil-borne pathogens include Bacillus anthracis (causing anthrax), Clostridium tetani (tetanus), and Clostridium perfringens (gas gangrene). These organisms underscore the dual nature of soil prokaryotic communities, housing both indispensable partners and serious threats.

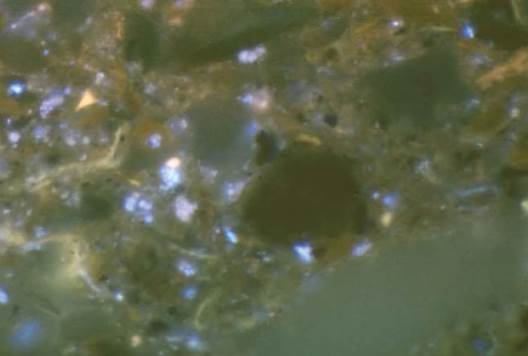

Fig. I.IV: Bacterial colonies in the image above are stained blue and can be seen scattered throughout this thin section of soil

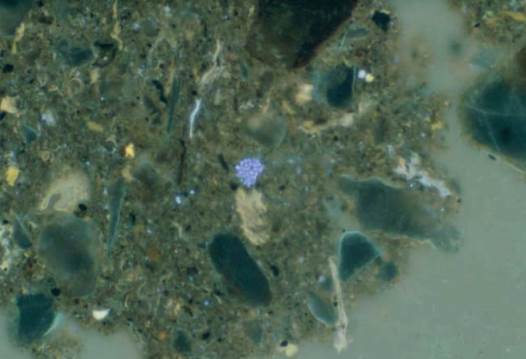

Fig. I.V: A bacterial colony, stained blue, growing within a very restrictive pore space

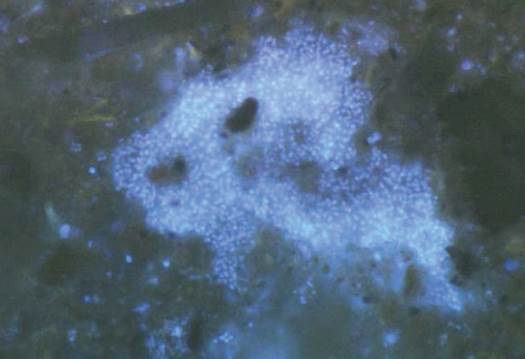

Fig. I.VI: A bacteria mega colony which grew in an arable soil after the addition of glucose. Nutrients are often limited in the soil system for bacteria, which therefore spend much of their time in a dormant or near dormant state, growing much more slowly than under ideal laboratory conditions

Microhabitats and Life Strategies. Within the soil matrix, bacterial colonies exist in water films within pore spaces between aggregates (see Fig. I.IV). Some occupy restrictive micropores (Fig. I.V), which limits colony expansion and nutrient access but offers protection from grazing protozoa. Soil’s dynamic nature, subject to wet-dry and freeze-thaw cycles, means these microhabitats are not permanently stable. Nutrients are often limited, forcing many bacteria into prolonged inactive, resting states. However, they can rapidly metabolize and reproduce upon nutrient influx before returning to dormancy (see Fig. I.VI).

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 160;