Soil Biodiversity: Measuring the Hidden World of Microbes and Organisms

Soil is a complex and dynamic ecosystem that hosts an extraordinary array of life far beyond familiar plants. This community includes animals utilizing soil for habitat and breeding, such as badgers, moles, and small herbivores, alongside lower plants like mosses, and a vast assemblage of invertebrates including beetles, spiders, mites, and earthworms. Crucially, it also encompasses the 'hidden' microscopic world of fungi, bacteria, and protozoa. The composition and diversity of this biological community vary significantly from one soil to another, forming unique and intricate living networks.

The diversity of microorganisms in soil is staggering in its scale. Current estimates suggest global soils contain approximately ten times more microbial cells than all the world's oceans. A single handful of grassland soil can harbor more microbial life than the total number of humans on Earth. These microbes are not only reservoirs of industrially valuable compounds but also execute vital roles in biogeochemical cycling and ecosystem sustainability. The collective organisms engage in complex interactions—predation, competition, symbiosis—constantly modifying their environment and facilitating each other's survival.

Understanding the structure, diversity, and ecological function of these microbial communities is fundamental to comprehending life strategies, evolution, and the overall functioning of terrestrial ecosystems. Consequently, measuring soil biodiversity presents a major scientific challenge and frontier. For larger organisms like plants and many invertebrates, conventional taxonomic identification is relatively straightforward. For microorganisms, however, this approach is severely limited, necessitating alternative methods to describe diversity in genetic and functional terms.

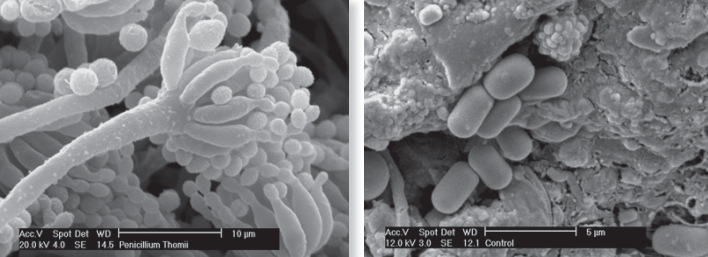

Our understanding of microscopic life forms remains incomplete. While some, like ornate protozoa, can be distinguished and counted under a microscope (Fig. 8.1), many, particularly bacteria, are morphologically indistinct. Traditional culture-based techniques, involving growth on special media (Fig. 8.2), are profoundly limiting. We now know through DNA fingerprinting that the tiny fraction of microbes culturable in the lab is not representative of the true microbial diversity present in soil.

Fig. 8.1: In some instances morphological differences exist between species as shown above with fungal spore bearing structures on the left, but in many cases different bacterial species can look identical morphologically as shown on the right

Fig. 8.2: Bacterial cultures isolated from soil growing on a synthetic growth medium. Each dot represents a colony of microorganisms that started as just one cell

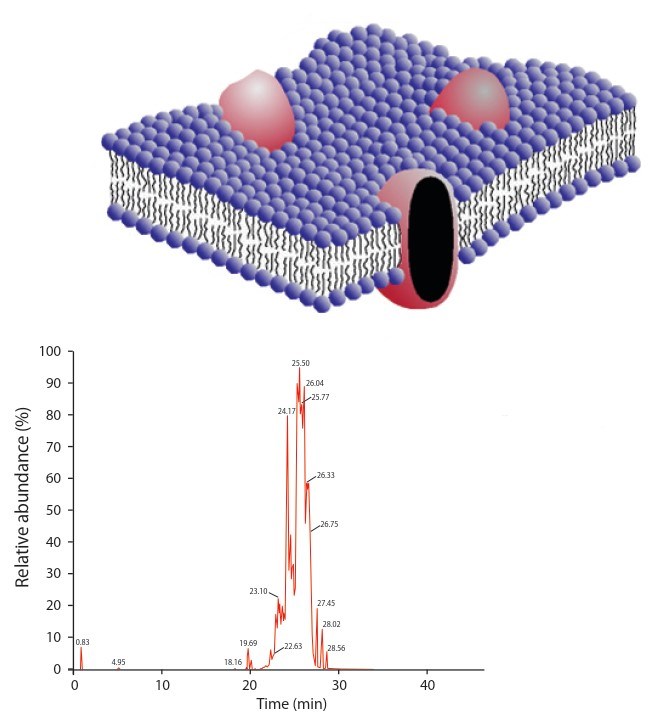

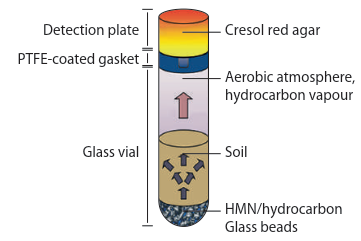

Modern analysis relies on extracting material directly from the soil matrix. Biochemical techniques, such as analyzing signature lipids in cell walls (Fig. 8.3), allow researchers to quantify broad microbial groups like fungi and bacteria without the bias of cultivation. Another approach assesses functional attributes by measuring how communities metabolize substrates or produce enzymes, often using colorimetric indicators (Fig. 8.4). Enzymatic activity, driven by intracellular and extracellular proteins, is a key functional output of soil biodiversity.

Fig. 8.3 : The membranes of all living cells are made up of 2 layers of phospholipids known as the lipid bi-layer (blue) as well as proteins (red) (above). The phospholipids vary in their molecular structure, such as the number of carbon atoms that they contain. Different microorganisms contain different proportions of these lipids in their cellular membranes and these can be extracted and quantified through a technique called gas chromatography (left). This allows quantification of the proportions of each phospholipids within a soil sample, which together produces a ‘fingerprint’ of the microbial community. Through comparisons of different community fingerprints the effects of different variables or changes in community structure over space or time can be investigated and quantified

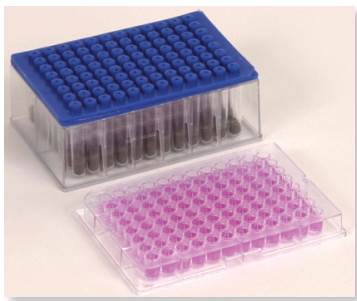

Fig. 8.4: Biochemical tests can be performed on both soil extracts and whole-soil and the rates of reaction measured to give a metabolic profile. For example, in one form of biochemical test, homogenised soil is added to plates containing a range of substrates (top right). After incubation for a period of time the CO2 respired as the microbial community utilises the different substrates reacts with a chemical in the gel leading to a change in colour (right). By analysing the amount of colour change it is possible to calculate the amount of CO2 respired by the community in response to different substrates and so differences in the metabolic abilities of microbial communities from different areas or exposed to different stressors can be quantified

Advancing further, proteomic techniques aim to extract and separate soil proteins via gel electrophoresis to identify their functions, though soil's complex chemistry presents technical hurdles. Among all direct extraction methods, those analyzing DNA or RNA have revolutionized our perception of soil biodiversity. The advent of high-throughput molecular sequencing enables the genetic "barcoding" of entire communities, a technique central to metagenomics. This has provided unprecedented data, revealing an explosion of previously unknown genetic diversity.

Current estimates of microbial diversity in soil are continually revised, ranging from thousands to millions of species per gram. Given this enormity, soil is rightly considered a primary search zone for novel biological discoveries, including new enzymes, bioactive compounds, and genetic resources. Fully describing and understanding Earth's soil biodiversity represents a significant scientific opportunity with profound implications for sustainability, medicine, and biotechnology. The integration of molecular, biochemical, and functional techniques is essential to unravel the complexities of this critical, life-sustaining habitat.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 95;