Molecular Analysis of Soil DNA: Techniques, Challenges, and Large-Scale Projects

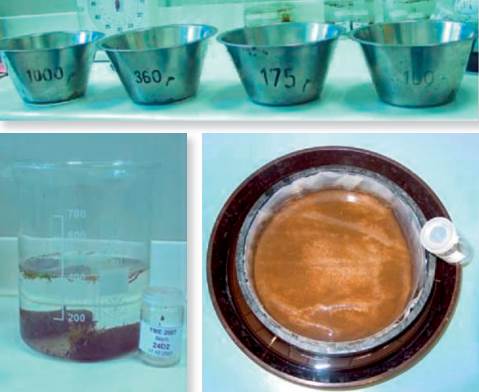

The molecular analysis of soil microbial communities begins with the extraction of genetic material from the complex soil matrix. Soil is first treated with surfactants, buffers, and solvents to lyse cells and release DNA. This crude extract undergoes purification and cleanup processes to remove humic acids, proteins, and other contaminants that inhibit enzymatic reactions, followed by DNA precipitation to concentrate the nucleic acids (Fig. 8.5). This yields a purified DNA template representative of the entire soil community, enabling downstream molecular techniques that probe its composition and function.

Fig. 8.5: DNA extracted from soil, cleaned and stained with a fluorescent dye. This small amount of DNA contains the sequences of tens of thousands of species

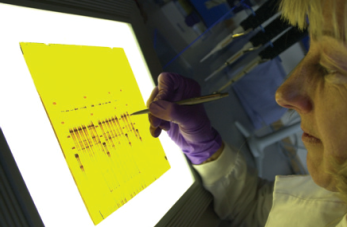

A common initial analysis involves the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Using specific synthetic DNA primers or probes that match conserved regions of taxonomic marker genes (like 16S rRNA for bacteria) or functional genes, target sequences are selectively amplified. Through repeated temperature cycles, DNA polymerase enzymes replicate these matched sequences, enriching them for detection. The amplified products can then be separated by gel electrophoresis to create a community fingerprint (Fig. 8.6). Individual bands can be excised and sequenced to determine their DNA code, providing identities for specific community members.

Fig. 8.6: Fragments of DNA from different species can be separated by electrophoresis on a gel seen here being visualised under UV light to show the DNA fluorescencing

To circumvent the selective bias inherent in PCR, alternative direct detection methods are employed. Fluorescently labeled molecular probes can be hybridized directly to soil DNA fragments, indicating the presence of specific genes. This principle is scaled up using microarray technology, where thousands of probes are spotted onto glass slides or chips. Arrays like the GeoChip are designed to detect a wide range of functional genes involved in nutrient cycling, degradation, and other processes, revealing which metabolic pathways are active in a soil sample and offering deep insights into functional diversity.

For comprehensive genetic inventory, high-throughput DNA sequencing is used. Sequence analysis determines the exact order of nucleotide base pairs (bp), which can be compared against global databases to identify genes and organisms. The advent of massive parallel sequencing technologies allows for the rapid sequencing of vast amounts of DNA from environmental samples. This metagenomic approach enables the characterization of entire community genomes, revealing both taxonomic makeup and functional potential without prior cultivation.

A current technical limitation is the read length of most high-throughput platforms, typically restricted to 200-500 bp. This can hinder precise taxonomic classification and the assembly of complete genes. However, emerging sequencing technologies capable of producing longer reads (up to 1000+ bp) promise to revolutionize taxonomic resolution and functional gene discovery, offering a more complete picture of soil biodiversity.

The sheer scale and complexity of soil microbial communities present monumental data handling and interpretive challenges. Initiatives like the TerraGenome project aim to systematically describe the complete soil metagenome from benchmark sites, such as the long-term Park Grass experiment in England. These projects mirror earlier large-scale genomic efforts but must contend with soil's unparalleled diversity, requiring sophisticated bioinformatics and immense computational resources.

Applying these molecular tools systematically across landscapes is now underway. High-throughput techniques are increasingly integrated into large-scale soil surveys, such as those in the European Union, to establish baseline data on microbial community variation. These surveys seek to understand how communities shift with soil properties, vegetation, and land management. Furthermore, the relative stability of DNA has led to the creation of soil DNA archives, preserving genetic snapshots for future retrospective analysis with more advanced technologies, thereby building a vital legacy dataset for global soil biodiversity research.

Soil Invertebrate Sampling Methods: ISO Standards for Earthworms, Nematodes & Microarthropods

Soil organism communities represent a cornerstone of terrestrial biodiversity, comprising thousands of species at a single site. While microorganisms dominate in terms of sheer numbers, and very few vertebrates, like the European mole, are permanent soil dwellers, a vast functional and taxonomic middle ground exists. This intermediate level is occupied by soil invertebrates, such as earthworms and Collembola (springtails), which are pivotal for soil health. Their sampling and identification require fundamentally different techniques than those used for microbes or larger animals, tailored to their specific ecology and size.

The choice of sampling methodology is critically dependent on the study's objective. For a qualitative overview of species presence, simple hand-collecting techniques are appropriate. However, for quantitative ecological research, monitoring, or legal soil quality assessment, standardized methods are essential. These methods must yield data on population density, biomass, and community composition per defined area or soil volume, enabling valid comparisons across time and space. To meet this need for standardization, the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) has developed guidelines under the title “Soil quality - Sampling of soil invertebrates.”

Given the immense diversity, ISO guidelines focus on key indicator groups: earthworms, enchytraeids, nematodes, microarthropods (e.g., springtails, mites), and macroarthropods (e.g., woodlice, millipedes). These guidelines detail the most appropriate technical methods, including necessary modifications for specific conditions like tropical climates. The use of these standardized protocols is strongly advised for any study where data may inform legal decisions, remediation efforts, or long-term environmental monitoring.

Sampling of Earthworms. Earthworms are globally recognized as crucial soil engineers, especially in temperate regions, and are the only group with an established ecotoxicological field testing method. The standard approach combines two techniques. The first is hand-sorting from a 50 x 50 cm (0.25 m²) plot to a depth of 10-20 cm (Fig. 8.8). This chemical-free method is labor-intensive and highly disruptive to the soil structure. The second is formalin extraction, applying a 0.5% solution to the same plot area to drive worms to the surface.

Fig. 8.8: Different techniques for extracting soil fauna from the soil. The techniques shown are: Formalin extraction and hand sorting of earthworms (photos to the left); electrical method for earthworm sampling (above middle), and a soil corer for extracting mesofauna groups (right)

The formalin extraction is particularly effective for anecic earthworms, which have deep vertical burrows. The irritant solution mimics the threat of waterlogging, prompting the worms to escape to the surface where they are collected. The required number of samples depends on soil properties and worm abundance (Fig. 8.8). Post-collection, specimens are fixed in 70% ethanol and can be stored long-term in 4% formalin or ethanol. For tropical applications, the Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility (TSBF)-Method uses hand-sorted monoliths and formalin spraying of soil layers. Alternative methods like electrical extraction (Fig. 8.8) exist but have limitations regarding cost and consistency.

Sampling of Enchytraeids. Enchytraeids, small oligochaete worms, are valuable bioindicators for soil acidification and nutrient cycling studies. They are quantitatively sampled using a split corer, typically 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 8.8). Laboratory extraction utilizes a wet extraction method (Fig. 8.9), a long-established behavioral technique. Soil cores are submerged and exposed to heat and light from above, exploiting the organisms' negative phototaxis and preference for cool, moist conditions.

Fig. 8.9: Wet extraction of enchytraeids

During wet extraction, enchytraeids migrate downward through the soil core and are collected in water. After extraction, they are counted alive, and biomass can be calculated. For taxonomic purposes, specimens are preserved for indefinite storage. Abundance data are then extrapolated to standard area (e.g., per square meter) or volume units, providing quantitative metrics for ecological assessment.

Sampling of Microarthropods. Among soil microarthropods, Collembola (springtails) and Acarina (mites) are most frequently studied due to their high abundance, diversity, and integral role in decomposition processes. Their importance in nutrient cycling makes them sensitive bioindicators for assessing soil quality changes from pollution or land use. Standardized monitoring builds upon classic ecological extraction methods.

Collection is done with a split corer (Fig. 8.8), allowing for stratified depth analysis. Extraction relies on behavioral responses, primarily using a Tulgren funnel or a MacFadyen high-gradient extractor (Fig. 8.10). These devices create a gradient of temperature and humidity, driving the arthropods downward out of the soil sample where they fall into a collection vessel. The Berlese-Tulgren funnel method is a cornerstone technique in this field.

Fig. 8.10: Collection of microarthropods using the Berlese-Tulgren funnel method

Sampling of Nematodes. Nematodes constitute a major and ubiquitous component of the soil fauna, found wherever moisture and organic matter are present. While known as plant and animal parasites, most soil nematode species are bacterivores or fungivores, driving decomposition. The field of nematology has strong agricultural roots due to crop pest species, leading to various methodological schools worldwide.

Fig. 8.11: Modified sieving and decanting method

For ecological monitoring, composite soil samples are taken with a corer (e.g., 2.5 cm diameter, 10 cm depth). A common extraction method is the sieving and decanting technique originally devised by Cobb in 1918 (Fig. 8.11). After extraction, nematodes are fixed in formalin and identified at least to the family level, allowing for ecological indices like the Maturity Index to be calculated, providing insights into soil ecosystem condition and disturbance.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 119;