Evolutionary Convergence in Soil Microarthropods: Adaptations and Ecological Significance

In evolutionary biology, evolutionary convergence is defined as the independent evolution of similar phenotypic traits in distantly related genealogical lineages. The intricate relationships between evolutionary processes and ecological drivers in facilitating such convergence remain a dynamic and relatively underexplored scientific frontier. Traditionally, convergence is explained through the adaptation orthodoxy, where similar environmental pressures select for analogous morphological solutions in unrelated species (Fig. 7.11). This principle suggests that shared habitats, like the soil matrix, can powerfully shape organismal form and function over deep time.

Fig. 7.11: Scorpion (left) and pseudoscorpion (right) show similar chelate structure on the pedipalpus

Morphological diversity is fundamentally the product of prolonged coevolution between organisms and their environments, intertwined with complex interactions among ecosystem components over more than 600 million years. Within the soil, microarthropods have emerged as critically important organisms for understanding ecosystem functioning. Several groups, such as Collembola (springtails) and mites (Acari), are extremely ancient, with fossil records dating to the Devonian period over 350 million years ago. Regarding their origins, soil microarthropods can be hypothetically divided into two broad categories based on their evolutionary history.

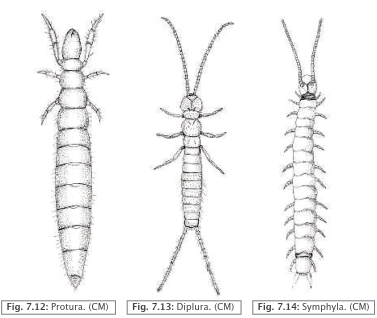

The first group likely originated in epigeous (above-ground) habitats and subsequently colonized and adapted to the soil environment. This category includes familiar arthropods such as Coleoptera (beetles), Chilopoda (centipedes), Diplopoda (millipedes), and Diptera (flies). The second group, in contrast, may have evolved directly within the soil substrate itself. This ensemble includes Protura (Fig. 7.12), Diplura (Fig. 7.13), Symphyla (Fig. 7.14), Pauropoda (Fig. 7.15), and Palpigrada (Fig. 7.16), which lack true epigeous or aquatic forms, with exceptions often confined to stable cave environments that mimic soil conditions.

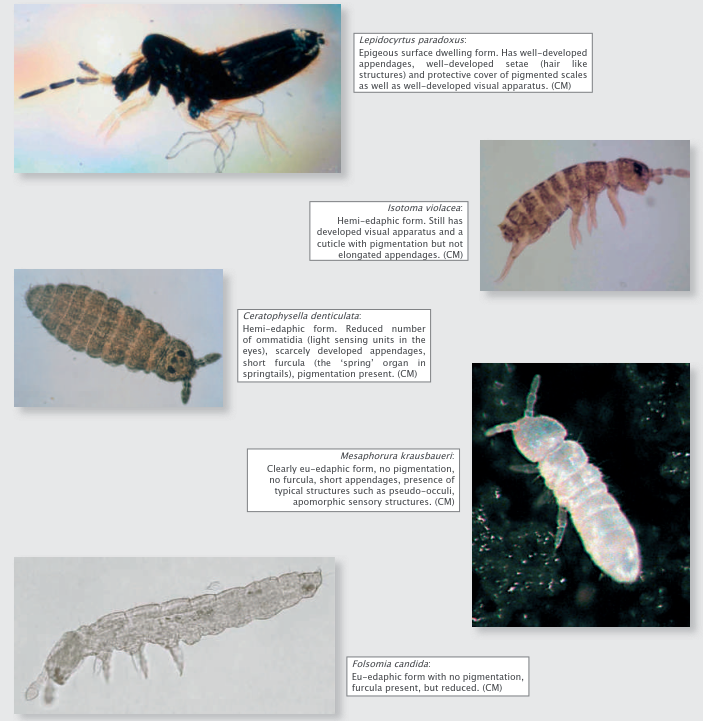

Over immense geological timescales, the bodies of truly soil-adapted euedaphic organisms have undergone profound specialization. This adaptive process has resulted in remarkable levels of convergent evolution, with many shared morphological adaptations being easily interpretable. Common convergent traits include the reduction or loss of eyes and visual apparatus, loss of body pigmentation or development of cryptic coloration, appendage reduction, and body miniaturization. These are often degenerative processes, where structures vital in above-ground habitats become superfluous in the dark, confined soil pore network.

Conversely, euedaphic microarthropods have positively evolved specialized structures essential for subterranean life. These include sophisticated chemoreceptors and hydroreceptors (humidity sensors). Unlike surface-dwelling relatives, these sensory organs are frequently distributed across various body regions, not solely concentrated near the mouth, enabling navigation and resource detection in a three-dimensional, dark environment. This sensory redistribution represents a key convergent innovation for life in soil.

The strict confinement of these groups to the soil habitat stems from the relative environmental stability found therein. Factors like moisture, temperature, and organic matter availability fluctuate far less dramatically in the short-to-medium term compared to above-ground conditions. Furthermore, sunlight is absent beyond a few millimeters' depth. Consequently, these highly specialized organisms are particularly sensitive to abrupt environmental changes and cannot survive outside their stable niche. They are acutely vulnerable to soil degradation from disturbances like intensive agriculture, compaction, and pollution.

Collembola (springtails) constitute one of the most significant and abundant groups of soil microarthropods, both in terms of species richness and individual numbers. They possess characteristics that make them exceptionally interesting for studying evolutionary convergence in soils (see box below; Fig. 7.17). Their long evolutionary history within this medium showcases a suite of convergent adaptations. Furthermore, Collembola are invaluable as bioindicators of soil quality, as their community biodiversity and population density are strongly influenced by key soil parameters. These include organic matter content, moisture, pH, and the presence of contaminants, making them sensitive markers of ecosystem health and disturbance.

Fig. 7.17: Different adaptation levels to soil in five species of Collembola

This exploration of convergent evolution among soil microarthropods underscores how powerful and predictable environmental filters can shape life. From degenerative losses to sophisticated sensory gains, the soil fauna presents a compelling case study in evolutionary adaptation. Understanding these patterns is not only crucial for fundamental evolutionary biology but also for applied conservation and sustainable land management, as these organisms are integral to soil formation, nutrient cycling, and overall ecosystem resilience.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 103;