Soil Community Ecology: Diversity, Interactions, and Functional Structure

Soil community ecology investigates the complex interactions between diverse soil organisms and the environmental factors controlling them. Despite their critical importance, knowledge of below-ground biota remains sparse compared to above-ground species. This gap stems from inherent study difficulties, as soil organisms are not easily observed and often lack the charismatic appeal of larger fauna. However, scientific interest dates back to the 17th century, as evidenced in historical records (Fig. 7.3). Soil biota are recognized as reservoirs for a major portion of global biodiversity and as governors of essential processes in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling.

Fig. 7.3: Oldest known picture of a soil mite

These organisms are fundamental to soil food webs and provide vital supporting and regulating ecosystem services (see Section 4.1). Rough estimates suggest several thousand invertebrate species can inhabit a single site, alongside immense, often uncatalogued, microbial and protozoan diversity. The dominant groups in both numbers and biomass are microorganisms—bacteria and fungi—with an estimated 10,000 to 100,000 distinct microbial genotypes per gram of soil. The animal community is also highly diverse, encompassing nematodes, microarthropods (mites and collembola), enchytraeids, earthworms, and various macrofauna like beetles and spiders. Soil invertebrates are typically classified by size into microfauna, mesofauna, and macrofauna.

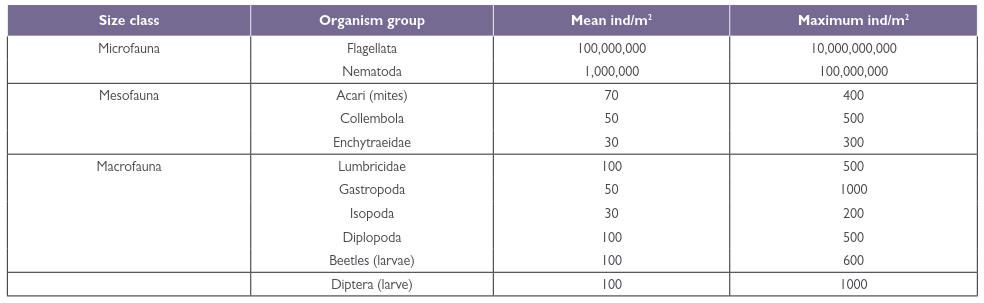

Providing average abundance or biomass values for soil invertebrates remains challenging due to high spatial-temporal variability and inconsistent methodologies. Furthermore, research has been biased toward temperate forest soils, neglecting tropical regions and agricultural systems. Table 7.1 illustrates abundance ranges for various groups in forest sites, with maxima often recorded under optimal conditions. For comparison, it also shows typically lower numbers in agricultural soils, which face threats from ploughing, compaction, and pesticides. A typical Central European earthworm population, for instance, averages 80 individuals and 5g dry weight per m².

Table 7.1: Abundance of the most important soil invertebrate groups in temperate regions (mainly forests); mean and maximum values

Soil fauna exhibit highly adaptable feeding strategies, ranging from herbivory and detritivory to predation and omnivory. Many species can shift strategies based on resource availability; for example, some carnivores may consume dead organic matter when prey is scarce. Interactions within the community are complex, extending beyond predator-prey dynamics to include commensalism. A notable example involves certain pseudoscorpion species that disperse by hitchhiking under the wing covers of beetles, benefiting from transport and protection without harming the beetle.

Fig. 7.5: Typical Portuguese cork oak forest

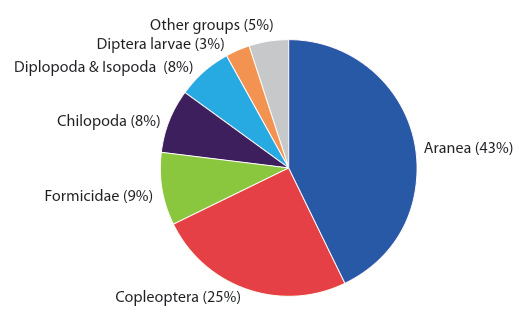

Fig. 7.6: Percentage of species richness of soil macroarthropods in a cork oak forest area in southern Portugal (samples taken using the ISO method)

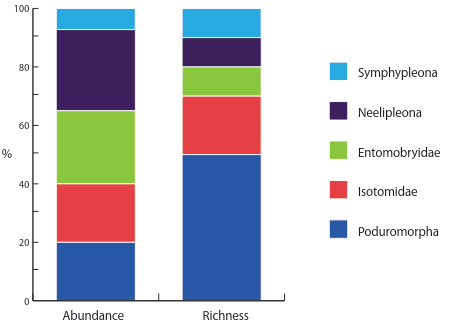

Fig. 7.7: Collembola community profile in terms of abundance and species richness in a cork oak forest area in southern Portugal (samples taken using a split corer according to the ISO method)

The composition of soil communities varies dramatically with ecosystem type. A typical Mediterranean oak forest (Fig. 7.5) soil community (Fig. 7.6) is often rich in macroarthropods like coleopterans, spiders, and ants, with diverse and abundant collembola populations (Fig. 7.7). In stark contrast, a Scandinavian coniferous forest on acidic mor soil is characterized by the near-absence of earthworms and macroarthropods, while enchytraeids, springtails, and mites reach high densities. Conversely, a Central European beech forest on richer mull soil is dominated by earthworms and supports diverse macrofauna (e.g., snails, diplopods), with mesofauna being less abundant than in acidic systems.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 83;