The Evolving Science of Soil Microbial Ecology and Biogeography

Soil microbial ecology is an interdisciplinary field synthesizing genetics, biochemistry, molecular biology, soil science, and environmental science. It addresses critical issues in agriculture, public health, and ecosystem stability. The study of microorganisms necessitates distinct concepts and methods compared to classical ecology. This is due to their minuscule size, the complex definition of bacterial species, and their immense genetic and metabolic diversity, especially within soil habitats. Consequently, researchers have developed specialized approaches to investigate microbial roles in ecosystem functions.

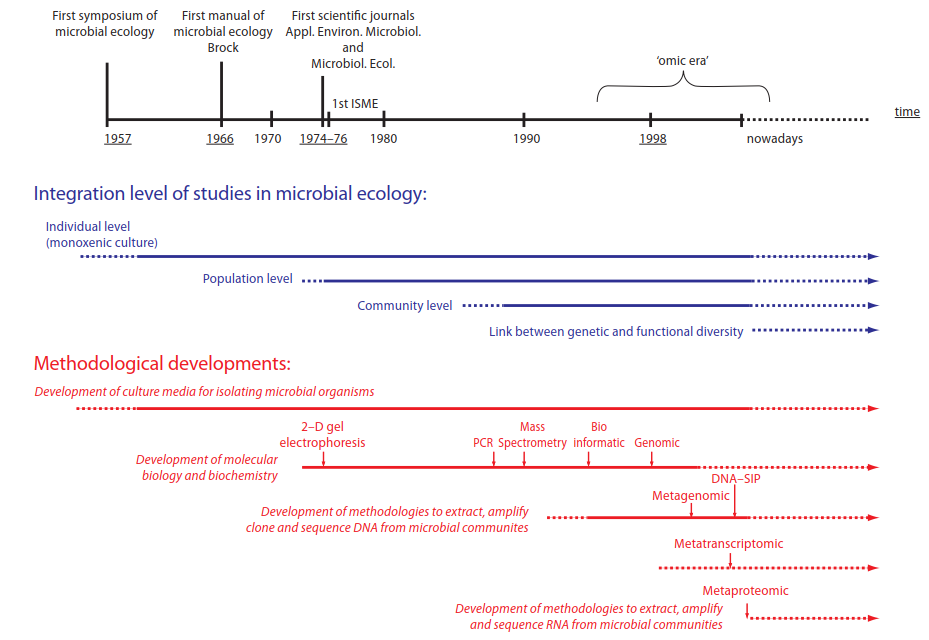

Historically rooted in medical and agronomic sciences, microbial ecology aims to clarify interactions between microbes and their environments, such as soil, water, and host organisms. The field has evolved stepwise in both methodology and conceptual understanding, as illustrated in Fig. 7.1. Early work in the 1960s primarily involved culturing single species in isolation, lacking ecological context. The 1980s marked a shift toward studying the density, diversity, and activity of natural microbial populations.

Fig. 7.1: Historical and salutatory evolution of microbial ecology (from Maron etal, 2007)

A major paradigm shift occurred in the 1990s with the advent of molecular methods. These techniques allowed for the analysis of nucleic acids like DNA extracted directly from environmental samples. This bypassed the limitations of culturing and enabled characterization of microbial community structure and diversity. These advances culminated in high-throughput screening and sequencing, providing access to the metagenome—the collective genetic material of all microbes in a sample. Most DNA sequences in repositories like GenBank now originate from such environmental studies.

Despite these powerful tools, many studies have merely catalogued diversity at specific sites or described community responses to disturbance. Data are often difficult to compare, leading to inconsistent trends and highlighting a lack of generalizability in the field. This underscores the need for more integrative frameworks that move beyond simple descriptive surveys.

From Microbial Community Analysis to Biogeography. Microorganisms represent Earth's most abundant and diverse life forms, yet the patterns and drivers of their spatial distribution—their biogeography—remain poorly understood. Studies on prokaryote diversification have traditionally focused on mutations, horizontal gene transfer, and environmental selection. Less attention has been paid to neutral processes like genetic drift, where isolated communities diverge genetically by chance. A critical gap has been the general failure to incorporate spatial scale into models of microbial community assembly.

While spatial analysis is fundamental in plant and animal ecology, its application to microbes is equally vital. It offers insights into how dispersal limitation, environmental heterogeneity, and evolutionary history shape communities. However, large-scale spatial studies of soil microbes are rare, and key biodiversity drivers are largely unidentified. Notably, the taxa-area relationship (the link between species number and area sampled), well-established for macroorganisms, remains insufficiently tested for microbes.

A longstanding hypothesis in microbial biogeography, originating from Beijerinck and formalized by Baas Becking, states "everything is everywhere, but the environment selects." This idea is supported by microbial traits: small size facilitating transport, ability to form resistant dormant stages, and enormous population sizes enhancing dispersal and reducing extinction risk. Evidence includes the global atmospheric transport of microbes and the discovery of bacteria, like thermophiles, in unexpected environments such as cold seawater.

The counter-hypothesis, "everything is not everywhere," proposes that dispersal limits create geographically isolated populations with restricted ranges, potentially leading to local speciation. Key unresolved questions include whether microbial communities exhibit predictable spatial aggregation, the relative importance of contemporary versus historical factors, and which environmental variables (e.g., soil pH, climate, land use) most influence diversity across geographic scales.

A synthesis of global data offers preliminary answers. It suggests that while local soil microbial diversity is high, regional diversity may be only moderate. Surprisingly, bacterial diversity appears decoupled from factors like temperature and latitude that strongly influence plants and animals. Community composition often shows little correlation with geographic distance. Soil pH emerges as a predominant factor, with neutral soils typically hosting greater diversity than acidic ones. Regional studies, such as in France, confirm that local factors like soil type and land cover are more influential than broad climatic or geomorphological characteristics.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate weak taxa-area relationships for soil microbes, indicating that microbial biogeography fundamentally differs from that of macroorganisms. The scarcity of definitive studies is due to technical challenges in resolving immense natural diversity and detecting rare populations. Furthermore, designing adequate large-scale sampling strategies requires analyzing thousands of spatially explicit samples, a logistical and analytical hurdle that has yet to be fully overcome.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 123;