Soil Biodiversity and the Global Carbon Cycle: Sinks, Sources, and Climate Feedbacks

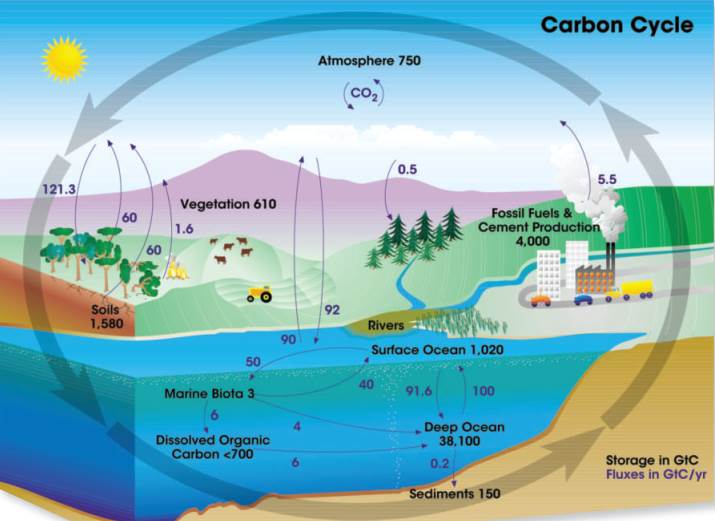

Soils play a critical role in the global carbon cycle, storing approximately twice the amount of carbon found in the atmosphere. Annual fluxes of hundreds of gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon occur between soil and the atmosphere (Fig. 5.19). Understanding these dynamics is vital for predicting climate change feedbacks and developing mitigation strategies. The simplified cycle in Fig. 5.19 shows a natural annual net atmospheric loss of 1.75 Gt carbon, based on well-established fluxes. However, relatively small anthropogenic emissions of 5.5 Gt C per year reverse this balance, creating a net atmospheric gain of 3.75 Gt C. This highlights the disproportionate impact of human activity on a finely tuned natural system.

Fig. 5.19: Schematic showing the carbon cycle. The black numbers indicate how much carbon is stored in various reservoirs, in billions of tons (GtC stands for Gigatonnes of Carbon and figures are circa 2004). The purple numbers indicate annual carbon flux between reservoirs. The sediments, as defined in this diagram, do not include the ~70 million GtC of carbonate rock and kerogen

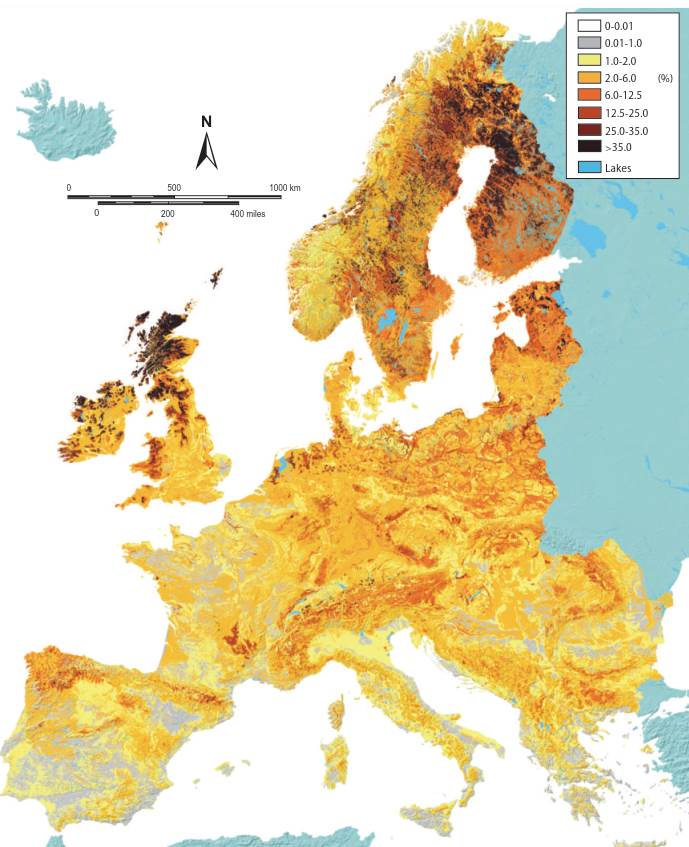

Soil organisms directly influence whether soils act as a carbon source or sink. In the UK alone, an estimated 13 million tons of soil organic carbon (SOC) are lost annually, equating to 8% of national emissions. Research indicates these losses may be linked more to soil organism activity and diversity than to inherent soil properties. While some soils are net sources, others function as sinks, with Fig. 5.21 depicting the heterogeneous distribution of soil carbon across Europe. A key climate feedback involves temperature: decomposition rates of soil organic matter (SOM) generally double with every 8–9°C increase in mean annual temperature.

Fig. 5.21: Distribution of organic carbon in European Soils

This temperature sensitivity suggests climate warming could accelerate SOC decomposition and increase atmospheric CO₂. Laboratory studies support this, showing sustained warming boosts microbial respiration, a primary CO₂ emission pathway. However, field observations of forest soils across latitudes show more constant decomposition rates, indicating complex compensatory mechanisms. This contradiction underscores the need for more ecosystem-scale research. Furthermore, soil biodiversity indirectly affects carbon storage by influencing erodibility through physical binding by fungal hyphae and soil aggregation. Severe erosion can convert a soil from a carbon sink to a source.

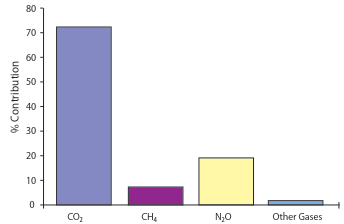

Beyond CO₂, soil biota are central to the production and consumption of other potent greenhouse gases. Methane (CH₄) is generated via methanogenesis by archaea under anaerobic conditions, such as in waterlogged wetlands and rice paddies. CH₄ is about 21 times more potent than CO₂ (Fig. 5.21). Conversely, methanotrophic bacteria consume methane, offering a potential biological mitigation pathway. Nitrous oxide (N₂O), with a warming potential 310 times that of CO₂, is produced by microbial nitrification and denitrification processes within the nitrogen cycle.

Fig. 5.20. There is much evidence from around the world that general climatic patterns are changing. In their 2000-2005 survey, the World Glacier Monitoring Service reported that virtually all glaciers under long-term observation in Switzerland, Austria, Italy and France were in retreat (the few that were not were stationary). The Mer de Glace, the largest glacier in France, has lost 8.3% of its length (1 km) in the last 130 years and thinned by 27% (150 m) in the midsection of the glacier since 1907

Fig. 5.20b: Contribution of gases to climate change (From natural and anthropogenic sources: excluding water vapour)

Managed ecosystems are significant contributors, responsible for 80% of N₂O and 50% of CH₄ emissions from soils. This stark increase over natural systems underscores the profound effect of agricultural and land management practices on greenhouse gas budgets. Although CO₂ constitutes roughly 83% of total emissions by volume, the combined radiative forcing of CH₄ (≈8% of emissions) and N₂O (≈5%) is substantial, as illustrated in Fig. 5.20b. Therefore, managing soil biodiversity and processes is crucial for mitigating both carbon and non-carbon greenhouse gas fluxes in a changing climate.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 104;