Wildfires and Land Degradation: Impacts on Soil and Peatland Ecosystems

The direct and indirect effects of wildfires significantly exacerbate land degradation processes and can advance desertification. This occurs through combined mechanisms of soil erosion, salinization, compaction, and a pronounced decline in soil biodiversity. Post-fire soil erosion intensifies dramatically because the protective vegetation cover and litter layer are consumed, leaving soil exposed to raindrop impact and surface runoff (see Fig. 5.8). Furthermore, fire severity influences soil structure and water holding capacity, which are degraded by the combustion of soil organic matter (SOM) and potential formation of hydrophobic layers. The preferential erosion of low-density organic particles strips away vital substrate, and severe erosion events can physically remove soil organisms from deeper horizons.

Fig. 5.8: Rainmakers: Wildfires can leave the soil very susceptible to both water and wind erosion processes, one of the main components of land degradation and desertification. Here, scientists are simulating rainfall, after a wildfire in a Eucalyptus plantation, and measuring soil erosion by water

Increased evaporation from bare soil often accelerates soil salinisation, creating additional physiological stress for surviving soil biota. Although commonly linked to Mediterranean climates, wildfires are a global phenomenon, occurring in boreal forests and northern latitudes (Figure 5.11) and critically, in peatland ecosystems. Peatlands, where partially decayed organic matter accumulates over millennia (see Section 3.2), represent a key carbon sink. In boreal regions, fire is a natural ecosystem component with historical return intervals of 60-475 years, though human activities like drainage and ignition have increased frequency up to tenfold.

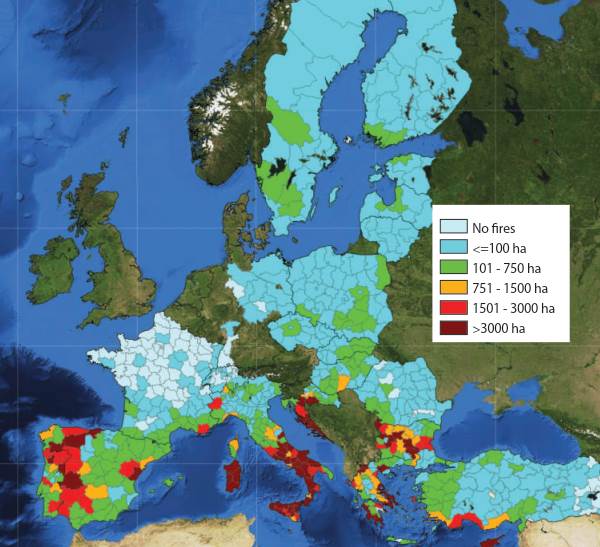

Fig. 5.11: Fire history map of Europe (burnt area) at NUTS3 level for 2007

Despite covering only 3% of Earth's land surface, peatlands store 15-30% of global soil organic carbon. Wildfires here, as demonstrated by the 1997 Borneo fires, can release vast quantities of greenhouse gases. These soils are largely composed of sphagnum moss, a genus of over 350 species capable of holding 20 times its weight in water. As new moss grows, older layers compact into peat. When water tables fall, sub-surface fires can ignite, smoldering for years. Even modest drying allows surface vegetation to burn (see Fig. 5.9). Notably, fire heat can "bleach" sphagnum without combustion, forming distinctive white hummocks termed "sphagnum sheep" (Figure 5.10), with recovery dependent on fire severity.

Fig. 5.9: Peatland surface wildfire in the Silver Flower NP, Scotland, April 2007

Fig. 5.10: ‘Sphagnum sheep’. During the wildfire, hummocks of moss (Sphagnum) did not burn. However the heat of the fire ‘caused the normally colourful moss (left; RA) to become ‘bleached’ leaving white fluffy hummocks reminiscent of sheep (right; MT)

For peatland soil biota—vertebrates, invertebrates, and microbes—impacts are theorized to mirror those in mineral soils, though empirical data is scarce. Given that peatlands are often nutrient-poor, acidic, and host high endemism, wildfires may impose disproportionately severe biodiversity losses. This underscores a critical need for targeted research to elucidate specific effects and ecological mechanisms in these sensitive carbon-rich ecosystems.

Future Wildfire Risks in Europe. While wildfire is a natural ecological process, human activity is the dominant cause, as shown in Figure 5.6. To monitor this threat, the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) was established by the European Commission's Joint Research Centre and Directorate General for Environment. EFFIS provides comprehensive pan-European fire data and historical analysis (see Figure 5.11), essential for detecting long-term trends.

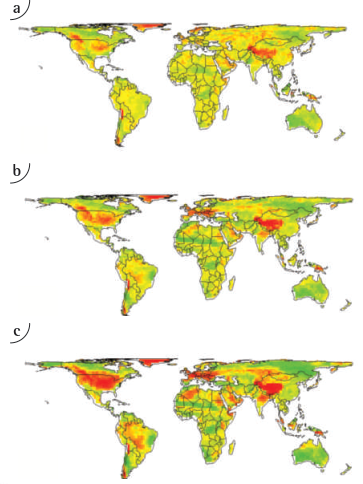

Fig. 5.12: Increased wildfires in Europe? Modelled changes in global distribution of wildfire. Colours indicate relative change in risk. Green indicates a decrease in fire occurrence, yellow no change, and red an increase. A=2010-2039; B=2040-2069; C=2070-2099 (Krawchuk et al., 2009)

Projecting future wildfire patterns—in frequency, extent, and intensity—under climate change remains complex and is the focus of extensive modeling. A primary challenge involves accurately simulating human behavior and responses. Figure 5.12 presents one model projection using a moderate climate change scenario, incorporating variables like human influence, lightning occurrence, and net primary production (as a proxy for fuel availability). This coarse-scale model indicates substantial regional variation, forecasting a significant increase in wildfire occurrence across Europe throughout the 21st century, highlighting a growing environmental and management challenge.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 94;