Understanding Wildfire Impacts on Soil Biodiversity: Direct and Indirect Effects

As introduced previously, this analysis delves into three specific threats to soil biodiversity, selected for their relevance to a general audience. The first, wildfires, exert complex direct and indirect influences on soil life across immediate and extended timescales. Direct impacts encompass the injury or mortality of soil organisms due to the conductive heat wave penetrating the soil, partial combustion, and outright habitat loss. Indirect consequences arise from post-fire alterations to nutrient availability, soil pH, soil organic matter (SOM) content, and the hydrological properties of the affected land. The temporal scale of effects is broad, ranging from a short-term nutrient flush from ash to medium-term development of soil hydrophobic layers, and long-term soil destruction from sub-surface fires or erosion following intense rainfall on exposed ground (Fig. 5.7, bottom left).

Fig. 5.7: Wildfires. Top left: Raging wildfire at night, Coimbra, Portugal, 2005 (AF); Top right: Ground fire aftermath. Trees are only slightly damaged, but the ground layer vegetation has been destroyed and a small subsurface fire can be seen (JK); Bottom left: wildfire has removed the entire vegetation cover. The soil surface is now very vulnerable to erosion by wind and rain (AF); Bottom right: wildfire threatening a population centre, Coimbra, Portugal, 2005. (AF)

To fully assess these impacts, distinguishing between the three primary wildfire types is essential: crown fires, surface fires, and sub-surface fires. The most destructive to soil life are sub-surface fires, which combust the soil matrix itself. These occur primarily in organic soils like peatlands or thick forest litter layers (Fig. 5.7, top right), spreading slowly but consuming both the habitat and the organisms within it. More common are surface fires, whose spread rate depends on fuel moisture and meteorological conditions like wind. These can ignite sub-surface fires or, in forests, transition into rapidly spreading crown fires. While crown fires are intensely destructive aboveground, they generally affect soil organisms only indirectly and to a lesser degree.

Although natural sub-surface fires are relatively rare, managed prescribed burning for wildfire prevention or land management is common and significantly impacts the litter layer and its dependent organisms. The heat wave from a surface fire can penetrate the soil, thermally altering SOM and lethally affecting biota in the top centimeters. Critically, soil biology is vulnerable at much lower temperatures than soil physicochemical properties. Even below 50°C, plant roots and small mammals can perish. Specific thermal thresholds exist: fungi in wet soil die around 60°C, seeds at 70°C, nitrifying bacteria at 80°C, and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae near 95°C. Soil moisture modulates these thresholds; drier soils exhibit higher tolerance, with fungi perishing at 80°C and seeds at 90°C, due to water's higher thermal conductivity and the prevalence of drought-resistant spores.

Soil organisms employ three core survival strategies: escape, concealment, or protection via resistant structures like spores. Mobile vertebrates (amphibians, reptiles, rodents) often survive by burrowing or fleeing, though indirect post-fire effects like habitat loss and increased predation can reduce populations. Conversely, less mobile soil invertebrates (ants, beetles, collembola) suffer greater direct mortality, especially species inhabiting the vulnerable litter and topsoil layers. For these, recovery depends on re-colonization from unburnt perimeter areas, influenced by the burnt patch's size, shape, and connectivity.

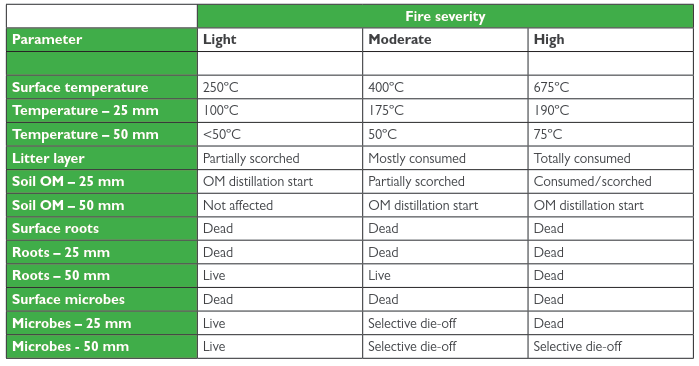

Table 5.1: Effects of fire intensity on soil temperatures, organic matter, and root and microbial mortality

Microbial responses to fire are exceptionally diverse, mirroring the complexity of the communities themselves. Generalizations can be made, as summarized in Table 5.1. Lethal temperatures for soil bacteria range widely from 50°C to 210°C. Typically, soil fungi are more heat-sensitive than bacteria, though some studies note post-fire increases in fungal functional diversity. Mycorrhizal colonisation of plant roots may either decrease or increase after burning, contingent on environmental factors. Ultimately, microbial recolonization proceeds primarily from viable populations in deeper soil refuges or adjacent unburnt patches.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 98;